What Hockney’s Arrival of Spring Series Tells Us About Vision and Technology

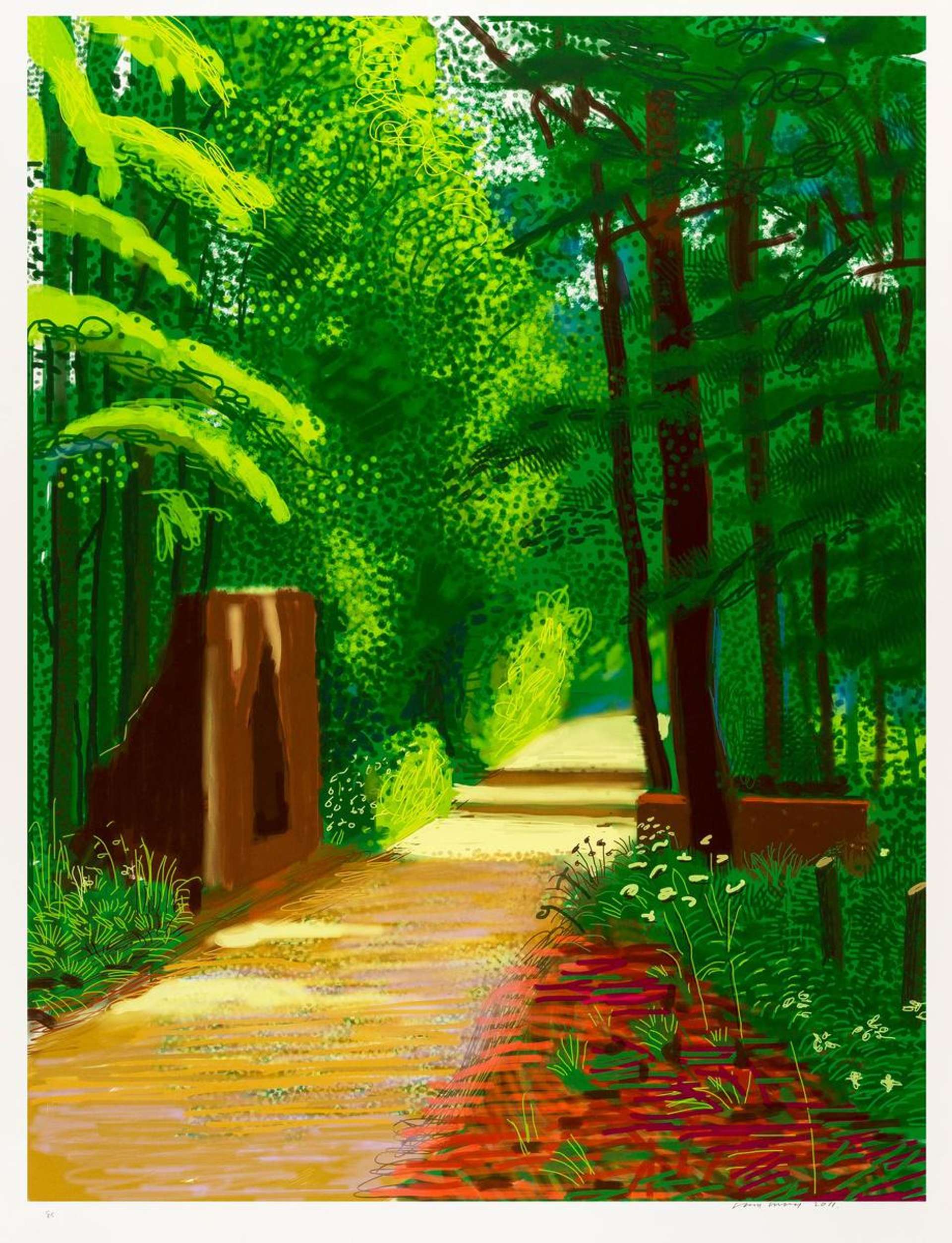

The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011 (twenty eleven) - 24 April © David Hockney 2011

The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011 (twenty eleven) - 24 April © David Hockney 2011Market Reports

As Sotheby’s prepares to sell the largest group of David Hockney’s iPad drawings ever to appear at auction, Charlotte Stewart argues that The Arrival of Spring is more than a digital curiosity. It’s a lesson in creative courage - and a reminder that true visionaries don’t fear new tools, something the art market itself should take on board.

David Hockney’s iPad drawings at Sotheby’s

This week at Sotheby’s London, seventeen iPad drawings by David Hockney will go under the hammer. It is the largest group of his digital works ever to appear at auction. Estimates run up to £180,000 each, a figure that will no doubt trigger a few scoffs from those who still think digital art belongs on an Instagram feed rather than a salesroom wall. But they miss the point. These aren’t experiments in novelty, rather proof of something far more profound: that true visionaries don’t wait for permission to use new tools, they just use them better.

When Hockney first began drawing on an iPad around 2011, most of his peers were still pretending email was a passing fad. He was in his mid seventies, a stage of life when most artists are being curated, not innovating, yet he picked up a tablet and started again. Such pioneering behaviour has become a ‘Hockneyism’. The resulting series, The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire, was unveiled at the Royal Academy in 2012, a blaze of colour that turned the English landscape into a theatre of renewal. It was a statement of creative agility: digital light, natural rhythm, and painterly instinct fused through the tip of a stylus. He is said to have done it in part as his beloved Yorkshire was too cold to stand en plein air for longer with traditional materials.

The series marked a literal and symbolic homecoming for Hockney. Having returned to his native Yorkshire after decades in California, Hockney set out to capture the slow unfurling of a northern spring, from the skeletal greys of January to the lush, almost perfumed greens of June. Each image records the same stretch of Woldgate, a country road flanked by trees, rendered with his signature vanishing-point perspective. What could have been repetitive became revelatory.

Hockney originally conceived The Arrival of Spring as a single work: one monumental oil painting accompanied by 51 iPad drawings, later divided into editions of varying scale. Like his 1980s “joiner” photo collages and his Four Seasons multi-screen video installation, which filmed the same Yorkshire lane through winter, spring, summer, and autumn, the series pushes at the boundaries of perception. The iPad became both sketchbook and lens, a device capable of recording the fugitive nuances of light with a speed no brush could match.

The critics - as they tend to be with every new artistic expression with the use of technology, since time began - were split. Some dismissed the works as bland digital novelties. Others saw them for what they were: a profound reassertion of painting’s timeless concerns: light, time and observation, through the most modern of means. Hockney’s iPad lines mimic the gestures of etching and lithography, the flicks and stipples of the hand still visible, only now translated through pixels. One cannot help but be reminded touchingly through the iPad medium that Hockney is primarily a printmaker - regardless of his paintings making the biggest ripples (such as his $50million+ Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy portrait coming to auction at Christie's in New York this November) . As with so many printmakers at heart, his intention wasn’t to abandon the analogue, but to bridge it. The screen, for him, was just another surface and allowed him to mass produce his work - much like Warhol was doing so in his Factory in 1963. Hockney was able to send the image as gifts to friends instantly. What better evolution of the print medium?

However, The Arrival of Spring stands firmly within a lineage of landscape experimentation, from Monet’s serial studies of Rouen Cathedral to Van Gogh’s feverish orchards. But Hockney’s intervention is uniquely 21st-century. He reclaims the digital from its reputation for disposability. In his hands, the iPad isn’t a gadget; it’s a conduit. The speed of the device mirrors the speed of seasonal change, its luminosity echoing the crisp Yorkshire light. This is not the flattening of tradition but its evolution.

Hockney Market Watch: Arrival Of Spring Prices And Demand

Demand isn’t theoretical. Ten years after they were produced, The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire, 4 May 2011 became the top-performing Hockney print at auction, fetching over £500,000 at Phillips London, up more than tenfold from its 2018 sale.

The appetite reflects something deeper than fashion. Collectors are recognising these works not as digital curiosities but as a continuation of Hockney’s lifelong interrogation of how we see, through optics, through devices, through time.

He understood something crucial: technology doesn’t replace the artist’s hand; it extends it.

That distinction matters. Because while the art world often fetishises innovation in theory, it resists it in practice. The same industry that celebrates Hockney’s genius often recoils from technological change when it touches its own systems, valuations, transactions, or transparency. If Hockney had waited for institutional approval before picking up his iPad, The Arrival of Spring would never have arrived. Yet our market still behaves like it needs committee meetings to sanction progress.

What The Art Market Should Learn From Hockney’s Approach To Tech

We live in this art market, to borrow my favourite phrase, at the intersection of clicks and connoisseurship. Buying art has never been easier. Understanding it - truly understanding it - has never been harder. Information is abundant, but expertise has become endangered. A new generation of collectors, raised on digital fluency and algorithmic taste, can buy a Hockney with the same frictionless ease as ordering a cab. But they also crave what can’t be automated: authority, authenticity, human insight.

That’s the irony of the “click age” in the art world. The technology that gives us access also threatens to flatten judgment. Hockney’s iPad works remind us that mastery isn’t about rejecting new tools - it’s about bringing them into the fold of skill, sensitivity, and experience. When he reached for his iPad, it wasn’t to digitise his art but to accelerate his seeing. He moved with the same curiosity that defined his entire career - from photocopiers to fax machines to multi-screen video. Each time, the medium was new, but the question was eternal: how do we see, and how do we make others see?

That’s why The Arrival of Spring isn’t just a technical experiment; it’s a philosophical statement. It tells us that creative integrity doesn’t dissolve in the digital. It migrates. The problem isn’t the technology - it’s the timidity with which many of us approach it, especially in the art market.

Artists have always adapted faster than the institutions that claim to represent them. The art business could learn a lot from Hockney’s nerve. He didn’t ask whether the iPad was “valid.” He picked it up and got on with it. He saw potential where others saw a duplicator. It reminds me of how print itself in the early 20th century was received.

And that’s the quiet revolution inside these works. They’re not nostalgic, nor are they disruptive for disruption’s sake. They’re proof that vision isn’t tied to youth, or medium, or market conditions.

So as those luminous screens of Yorkshire blossom come to auction, each one born from a man in his seventies who decided to reinvent how he painted, the real question isn’t whether collectors will pay £180,000 for an iPad drawing - they will be. It’s whether the rest of the art world has the courage to follow his example.

Because this wasn’t a man fumbling with technology. This was a master, stylus in hand, showing the world what creative evolution really looks like. He didn’t debate it. He didn’t theorise it. He just picked up an Apple Pencil and got the hell on with it.

“Do remember: they can’t cancel the spring.”