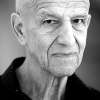

sir peter blake

Sir

Peter Blake

Buy art

Sell art

Market data

Be the first to know

Join our mailing list to be the first to hear about available Sir Peter Blake works in our network.

Sell Your Art

with Us

with Us

Join Our Network of Collectors. Buy, Sell and Track Demand

Submission takes less than 2 minutes & there's zero obligation to sell

The Only Dedicated Print Market IndexTracking 48,500 Auction HistoriesSpecialist Valuations at the Click of a Button Build Your PortfolioMonitor Demand & Supply in Network Sell For Free to our 25,000 Members