Forgery, Fakes & the Art Market’s Wild Years

Marilyn (F. & S. II.23) © Andy Warhol 1967

Marilyn (F. & S. II.23) © Andy Warhol 1967Live TradingFloor

Before catalogue raisonnés, digital databases or even much scrutiny, the art market of the 1980s ran on instinct, reputation – and the occasional sleight of hand. In this candid reflection, veteran dealer Richard Polsky revisits the early days of his career, when altering an edition number could pass for standard practice. As the stakes have risen and forgeries grown more sophisticated, so too has the business of authentication. From erased proofs to forged certificates, this is a firsthand account of what’s changed – and what hasn’t – in the murky world of identifying what’s real.

How Forgery Sparked My Career

Every business evolves – and the art authentication business is no exception. Back in 1978, I was living in San Francisco. I typically walked to work every morning to my job at Foster Goldstrom Fine Arts. I always took the same route down Sutter Street, which was lined with contemporary art galleries. If time permitted, I would stop by a few spaces to check on the competition. There was a particular gallery (which shall remain nameless), that I often visited – not so much for the quality of the work they exhibited but for their questionable behavior.

One day I walked into the gallery and noticed the owner was leaning over an unframed Marc Chagall print. He had a Mars plastic eraser in his hand and looked up when he spotted me.

With glee he said, “Want to learn how to make $5,000 in the art business?”

Before I could answer, he began erasing the letters “AP” in the margin. Then he took a pencil and quickly scribbled in “7/50.”

I began to chuckle, “What are you doing?”

He went on to explain how collectors preferred to buy a print that was from the numbered edition rather than an artist’s proof. With the owner’s slight-of-hand he managed to, in theory, increase the value of his inventory. When I walked out of the gallery, I shook my head in disbelief. Later that day at work, I mentioned the incident to Foster Goldstrom. With a smile, he said, “Believe me, I’ve seen much worse.” At that point, my career in the art world was exactly a month old. I couldn’t wait to see what happened next – and I wasn’t disappointed.

As everyone knows, fraud is part of the art market – always has been and always will be. Not that the art industry is different from any other industry. Where there’s money to be made unscrupulous individuals will always find a way to cheat. What separates the art market from other businesses is its lack of regulation – anything goes.

Telling Someone It’s Not a Real Warhol Never Gets Easier

Literally ten years ago, I started Richard Polsky Art Authentication with the intention of exclusively authenticating the work of Andy Warhol. I remember my wife saying to me, “Aren’t you going to run out of Warhols to authenticate?” I responded, “Probably not. As Warhol’s value continues to grow the number of fakes are going to go up exponentially.” Not to pat myself on the back, but I was right.

As art has become universally viewed as an investment, it stands to reason that people are going to find a way to game the system. We have always received a consistent stream of inquires from people who think they own a Warhol. What’s changed over time is how people often take my reports personally. Sometimes, these paintings were inherited from a parent or a grandparent. If I inform one of these inheritors that they don’t own an Andy Warhol, they frequently say, “Are you calling my deceased mother a liar?” I then have to tactfully explain that I’m not saying that your mother is a liar – I’m just saying that it’s not an Andy Warhol.

The Rise of Forged Certificates & the Decline of Authenticators

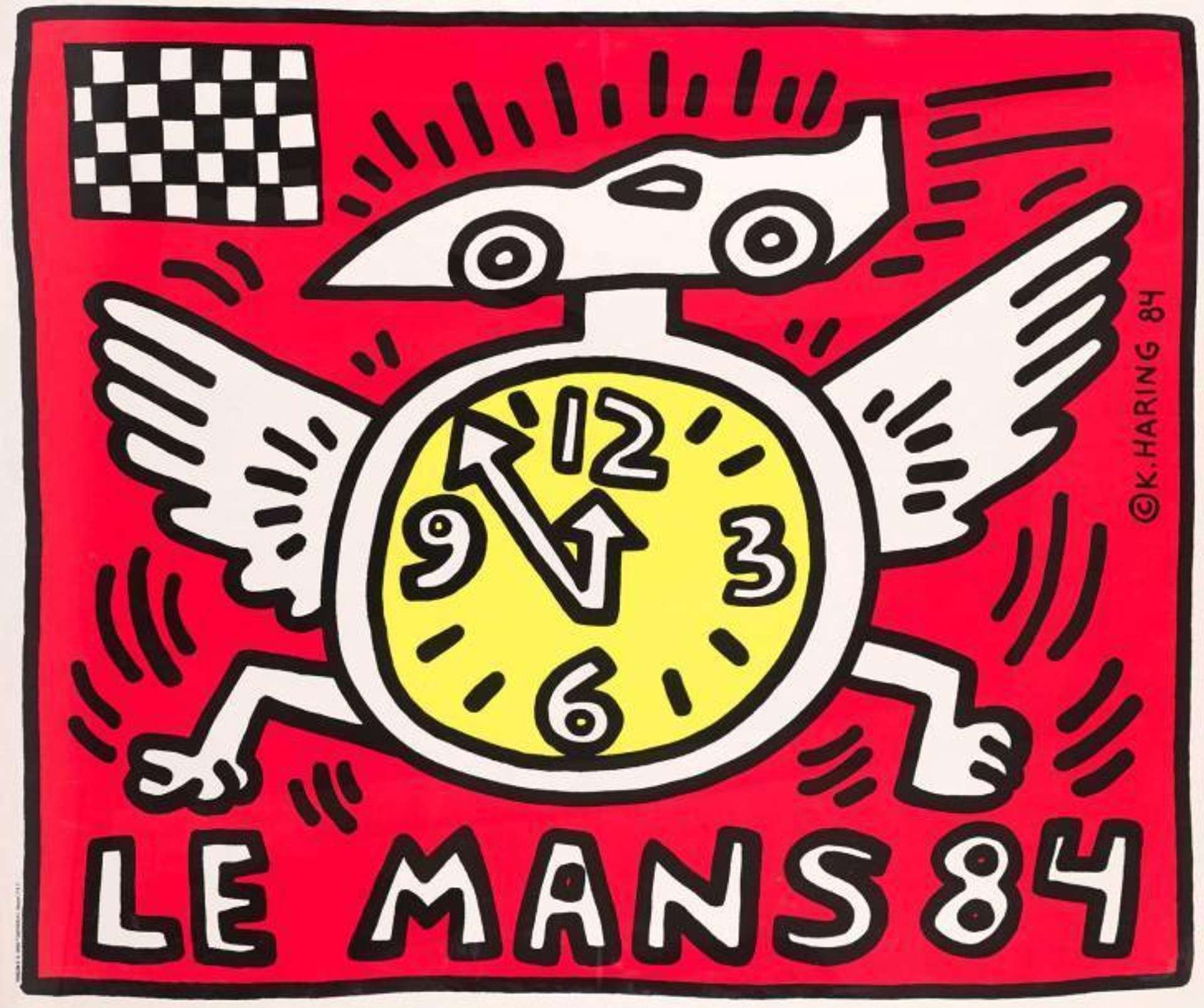

One of the biggest changes over the years has been the proliferation of forged authentication certificates, which attempt to duplicate those issued by the Keith Haring Foundation and the Authentication Committee of the Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Prior to 2012, when estate art authentication boards were still open, they issued certificates of authenticity. These certificates varied in their complexity. Some of them had gold seals, some of them were printed on elaborate stationery, and all of them had an appropriate signature. An estate certificate was the difference between Sotheby’s accepting your work for auction (and an ensuing large payday) and not. Fortunately, we have copies of the certificates issued by the original art authentication boards which allow us to weigh in on the authenticity of examples submitted to us.

An interesting aside was Carl Andre’s unique approach to assuring the authenticity of his creations. Since some of his floor sculptures were made from industrial steel tiles, they were easy to fake. Andre circumvented this issue by offering his own certificates. However, he charged for this service. You would have to pay him with two $100 Canadian maple leaf gold coins.

Another reason forgeries are on the rise is because of the growth of online auction platforms, such as invaluable and live auctioneers, who don’t vet what they offer for sale. They use specific language in their contracts with buyers and sellers which absolve them of any responsibilities when it comes to authenticity. Dealing with buyers on these platforms has become one of the fastest growing segments of our authentication service.

You also have the proliferation of small regional auction houses (there are thousands of them worldwide) which lack the professional expertise to discern whether they are offering a genuine Basquiat, Haring, or Warhol. The problem is that these companies are generalists rather than specialists. If someone submits a painting to them that resembles a comic book panel, they assume it’s a Roy Lichtenstein.

What the Future Holds: Catalogue Raisonné Gaps and Online Chaos

In the future, we expect growth to come from clients whose works are genuine, but don’t appear in the appropriate catalogue raisonné. Currently, there are catalogues for Andy Warhol (still under production) and Roy Lichtenstein (online). Tony Shafrazi and Enrico Navarra attempted to compile catalogue raisonnés for Jean-Michel Basquiat’s paintings and drawings – which are useful but far from complete. We’re of the opinion that it would be a longshot if in the future someone put together a bona fide catalogue raisonné for Basquiat. As for Keith Haring, while the Keith Haring Foundation website includes a brief survey of his works, we are unaware of any plans for a catalogue raisonné.

The nature of any catalogue raisonné is that they’re imperfect. For example, the Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné of paintings and sculpture unintentionally included a few fakes (see: multi-image portrait of John Chamberlain) and some unfinished works (see: early works from the collection of Fred Hughes), along with a host of omissions. Once again, it is with the latter category that we expect increased requests for authentication.

Regardless, art fraud is a growth industry that shows little sign of slowing down. As always, the key for collectors is to know who you are dealing with. It remains prudent to pay a little more and work with a company that stands behind what they sell you, than to save a few bucks by working with an amateur auction house or unreliable online auction platform.