The Top 10 Artworks People Want to Own in Brazil

Image © Wikimedia Commons / Abaporu © Tarsila do Amaral 1928

Image © Wikimedia Commons / Abaporu © Tarsila do Amaral 1928Market Reports

If you could own any artwork in the world, what would it be – and why?

Isolating responses from Brazil offers a glimpse into the national psyche, revealing a love for both international masterpieces and homegrown icons. In particular, Brazil’s selections suggest a deep engagement with regional narratives, mythologies, and the politics of cultural heritage.

Understanding Brazilian Art Desires

Conducted in early 2025 and focused solely on responses from Brazil, the survey revealed that Brazilian participants, more than any other national group, combine a global appreciation for European masterworks with a strong impulse to honour and reclaim their own artistic heritage.

Topping the list is Tarsila do Amaral’s Abaporu, a modernist emblem that many respondents long to see returned home from Buenos Aires. Several participants linked their choices to formative childhood encounters with art, national pride, or the politics of where culturally significant works are displayed. Abaporu, in particular, emerged as both an artistic and political choice, its absence from Brazil symbolising larger questions of cultural repatriation. A closer look at the data also reveals a gendered pattern similar to the global findings: women drove the majority of votes for six of the ten artworks, while millennials were the most represented generation in seven of the ten.

Image © Wikimedia Commons / Abaporu © Tarsila do Amaral 1928

Image © Wikimedia Commons / Abaporu © Tarsila do Amaral 19281. Abaporu by Tarsila do Amaral

Claiming first place in Brazil’s voting is Abaporu, painted by Tarsila do Amaral in 1928 as a birthday gift to her husband Oswald de Andrade. Abaporu became the catalyst for Brazil’s Antropofagia (Cannibalist) movement: a call to “devour” European art and create something wholly Brazilian. Its towering, distorted figure, with its tiny head balanced atop an elongated body and enormous foot, sits beneath a blistering yellow sun and beside a spiny cactus. While art historian Michele Greet has noted its echo of Rodin’s The Thinker, Tarsila subverts that model’s emphasis on intellectual contemplation, grounding her figure in the earth rather than placing it on a pedestal.

Her shading recalls techniques learned from Fernand Léger during his “mechanical” period, yet here the rounded volumes belong not to an industrial world but to Brazil’s organic landscape. Drawing on European modernist languages of Cubism, Fauvism, and Expressionism, Tarsila reassigns their meanings to speak to Brazilian nature and identity, embodying the Antropofagia ideal of transforming imported culture into something local. Today, the original resides at MALBA in Buenos Aires, making its absence in Brazil a point of cultural contention.

For many Brazilian respondents, Abaporu is inseparable from national identity. “It is the Brazil I carry inside me,” wrote one, recalling how the first sight of the painting moved them to tears. Others praised its “vibrant colours” and its ability to “challenge colonial narratives” by highlighting indigenous symbolism and rejecting imported artistic hierarchies. Several said they would own it solely to return it to Brazil, one participant saying; “I would donate it to a public museum so it could inspire and provoke as it was always meant to.” Many recalled their earliest encounters in school art and literature classes, where Abaporu was taught as a foundation of modernism, one participant sharing; “it was the first time I looked at a work of art and felt I was in it.” Respondents also reflected on its political charge; “it is part of a disruptive movement… very meaningful to our history”, many objecting to its current home in the MALBA in Buenos Aires. For Abaporu, ownership is as much an act of repatriation as of appreciation.

Image © Wikimedia Commons / The Starry Night © Vincent van Gogh 1889

Image © Wikimedia Commons / The Starry Night © Vincent van Gogh 18892. The Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh

In second place among Brazil’s most-voted artworks is Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night (1889), painted in an asylum at Saint-Rémy. In this iconic artwork, a cobalt sky writhes with wind-driven swirls that navigate glowing stars, while a flame-shaped cypress rises above a village that sleeps under the night’s restless energy. This is not a static moonlit scene, in contrast, van Gogh’s thick impasto and rhythmic brushstrokes make the sky feel alive.

In Brazil, some remember first seeing Starry Night as children, one admitting; "I realised he had painted my dreams.” Another respondent linked the artwork to comfort - “despite all the problems of life”. In Brazil,66.67% of votes came from men, whereas globally women cited Starry Night more often than men, perhaps hinting at a stronger male identification with its solitude and stillness.

The connection also reads through a Brazilian lens: as in Candido Portinari’s O Lavrador de Café, skies are employed to dictate the mood of the composition, their sweeping clouds and shifting light mirroring the struggles, hopes, and endurance of people. In that sense, perhaps The Starry Night employs an artistic language that Brazilians already recognise in their own artistic heritage.

Image © Bygginredning.se / The Kiss © Gustav Klimt 1907-8

Image © Bygginredning.se / The Kiss © Gustav Klimt 1907-83. The Kiss by Gustav Klimt

Ranking third in Brazil’s favourite artworks was Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss (1907–08), an image swathed in gold leaf that captures a couple poised on the edge of a meadow and an abyss. The man’s robe is patterned with assertive black and white rectangles, the woman’s with gentle circles and flowers; a symbolic interplay of strength and nurture. The faces meet in a suspended moment of tenderness, the curve of her neck and closed eyes radiating a serenity that remedies the ambiguity of the setting.

Brazilian respondents approached The Kiss with a notable emotional intensity. Many spoke of the “warmth you can feel through the screen,” and the sense of “tender love”. Others recalled discovering the painting in childhood through books, music, or classroom projects, the image lodging itself in memory as the archetype of romantic devotion. Yet for some, the work’s power lay in its ambiguity: one questioned whether the woman’s closed eyes signified rapture or entrapment, seeing in it a reflection of their own questions about love’s dynamics.

In Brazil, 87.5% of votes came from women, a majority that echoes the global female majority, and Gen X formed the largest group at 37.5%, followed closely by Millennials and Gen Z. This suggests a cross-generational female identification with Klimt’s vision, whether embraced as an image of mutual desire or interrogated as a symbol of gendered vulnerability. For these viewers, The Kiss is capable of reflecting both the ecstasy and the unease that intimacy can hold.

Image: Picryl / The Birth of Venus © Sandro Botticelli c. 1486

Image: Picryl / The Birth of Venus © Sandro Botticelli c. 14864. The Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli

Taking fourth place is Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (c. 1485), which stages the goddess emerging from the sea upon a scallop shell, blown forward by Zephyr and greeted by a handmaiden with a floral cloak. The composition’s soft curves, pale hues, and rhythmic lines conjure an idealised beauty that is sensual and restrained, its Renaissance elegance carrying a mythic timelessness.

For Brazilian viewers, the painting often represents their first encounter with Renaissance art. Many recalled finding it in schoolbooks, captivated by its pastel palette and composition; one remembered being “caught by the colours, the curly hair, the whole scene,” while another linked it to meeting a woman whose beauty seemed to echo Venus herself. Some respondents also praised its influence on generations of artists, calling it a work they could “look at all day” without losing interest. In Brazil, The Birth of Venus drew an 80% female majority, suggesting the figure’s poise and balance between sensuality and modesty continues to resonate strongly with women.

Image © Wikimedia Commons / Empire of Light © Rene Magritte c. 1939 - 1967

Image © Wikimedia Commons / Empire of Light © Rene Magritte c. 1939 - 19675. Empire of Light by René Magritte

Claiming the halfway spot is René Magritte’s Empire of Light - an image with multiple versions, whose impact lies in the paradox of day and night sharing one sky. In the artwork, a quiet street glows under lamplight, a lone house lit from within, its reflection rippling across a stretch of water. A dark tree rises against a pale blue sky streaked with clouds, the serenity above refusing to match the darkness below. It is not overtly fantastical, but by pairing night and day in one image, Magritte destabilises one of the most basic structures of our reality. Sunlight, usually a source of clarity, feels unsettling, while the darkness is made to seem deeper and more impenetrable. Rendered in his typical Surrealist style, the scene’s ordinariness is exactly what makes it mysterious - an effect Magritte himself described as depicting “the most ordinary reality” until it loses its familiarity.

Brazilian admirers responded to this tension between the recognisable and the inexplicable. Some described their “epiphany” on first seeing it; “when you truly feel something just by looking at the canvas”, while others praised it as a “simple image full of mystery”. 66.67% of votes came from Millennials, suggesting a generational attraction to Surrealism’s disruptions: reality altered just enough to make us doubt what we know.

Image © Wikimedia Commons / Girl with a Pearl Earring © Johannes Vermeer c.1665

Image © Wikimedia Commons / Girl with a Pearl Earring © Johannes Vermeer c.16656. Girl with a Pearl Earring by Johannes Vermeer

Painted around 1665, and coming in sixth place, Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring is his most famous work. However, this painting is not a portrait but a tronie: a study of a made-up figure with an exaggerated expression, often used as studies in physiognomy. Here, a young woman appears in an oriental-style turban draped in folds of blue, wearing an improbably large pearl at her ear. Vermeer renders her face with softness, letting it emerge from the dark background as if illuminated from within. Highlights appear at her lips and in the pearl, amplifying the sense of a fleeting, intimate moment.

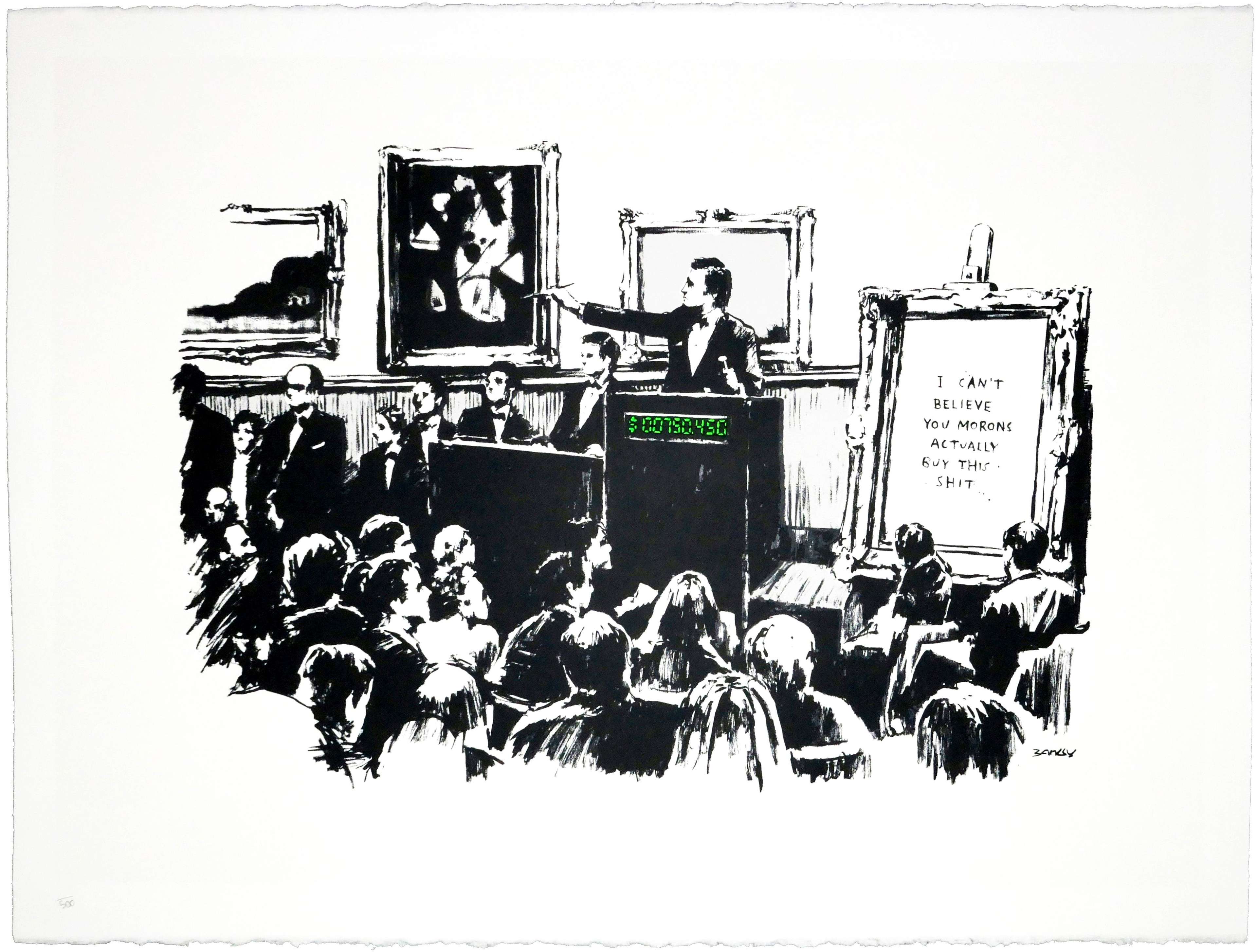

For Brazilian respondents, her magnetism is mentioned repeatedly. “The first time I saw her I was stunned,” wrote one respondent, while another imagined hanging her in their bedroom “to wake daily under her gaze.” Gen X leads in her admirers at 66.67%, suggesting a mature appreciation for Vermeer’s restraint, though Millennials also respond strongly to her quiet mystery. Her parted lips and turned head create a presence that has inspired countless reinterpretations, from cinema to street art, including Banksy’s Girl with a Pierced Eardrum - a testament to the image’s enduring pull and its place in global popular culture.

Image: Picryl / The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog © Caspar David Friedrich 1818

Image: Picryl / The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog © Caspar David Friedrich 18187. The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich

Ranking seventh is Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818); a quintessential Romantic vision of man in confrontation with nature’s vastness. At its centre, a figure in a dark overcoat stands on top of a precipice as he surveys a landscape swallowed in mist. His back is turned to us, withholding his identity and inviting us to share his vantage point instead. Distant mountain ridges rise and dissolve into cloud, their converging planes drawing the eye to the midpoint of the painting - and level with the man’s heart.

Over the past two centuries, the image has transcended its Romantic origins to become a cultural icon, appearing on book covers, accompanying music compositions, and even being parodied in television shows like Severance. Romanticism emerged as a reaction against the Enlightenment’s faith in reason and order, instead pursuing emotion, imagination, and the sublime; qualities Friedrich distilled into this solitary figure set against nature’s unfathomable scale. 100% of Brazilian respondents who chose it were male, and all were Millennials, making its demographic profile unusually unanimous. “I want to jump in the fog and discover it,” one wrote, while another saw it as a call to “brave the unknown.” For these viewers, the Wanderer embodies self-discovery and confrontation with life’s uncertain horizons.

Image © Flickr / The Winged Victory of Samothrace © c. 190 BC

Image © Flickr / The Winged Victory of Samothrace © c. 190 BC8. The Winged Victory of Samothrace

In eighth place is The Winged Victory of Samothrace, carved around the 2nd century BCE. Originally set within a sanctuary on the island of Samothrace, the sculpture was likely designed to commemorate a naval success, designed so that the goddess Nike leans forward into an invisible wind, her garments billowing with tension. The marble is carved so that the folds of her drapery seem to ripple against her body, creating an extraordinary illusion of movement. Although her head and arms have been lost, the figure still radiates the drama of triumph, her poised stride and outstretched wings capturing the triumph of victory.

Brazilian respondents spoke of the statue of Nike with a reverence that mirrors the awe she inspires in the Louvre’s grand staircase today. One admirer says she is “powerful and delicate,” with an “aura” that seemed to transcend time itself. Another respondent recalled the shock of seeing her in person, describing the experience as a life split into “before and after.” In the survey, votes were led by men (66.67%), reflecting the sculpture’s celebration of strength and victory that has long appealed to traditionally masculine ideals of heroism and conquest. For viewers in Brazil, The Winged Victory serves as an enduring emblem of resilience, proof that even in fragments, this artwork can command admiration and awe.

Image © Wikimedia / Apollo and Daphne © Gian Lorenzo Bernini 1622-1625

Image © Wikimedia / Apollo and Daphne © Gian Lorenzo Bernini 1622-16259. Apollo and Daphne by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne, ranking ninth in Brazil’s favourite artworks, shows the dramatic moment when Apollo is about to catch Daphne, and she transforms into a laurel tree to escape. As Apollo reaches for her, Daphne’s skin blossoms into bark, her fingers stretch into leaves, and her toes become roots that burrow into the marble ground. The sculpture breathes in defiance of its medium: the twist of Daphne’s body guides the viewer’s eye upwards, while Apollo’s forward momentum halts in shock and yearning. Created when Bernini was in his early twenties, the work exemplifies the Baroque’s love of drama, motion, and emotion.

Brazilian respondents spoke with awe about encountering the piece, even in reproduction. One viewer remembers being “mesmerised” by its combination of brutality and delicacy, and “details of the tiny leaves”. Another called it “one of the most stunning pieces I’ve ever seen,” astonished that marble could be so dynamic. The even gender split in responses suggests that its appeal is universal, resonating equally with those drawn to its romantic tragedy and its technical brilliance.

Image © Wikimedia Commons / Almond Blossom © Vincent van Gogh 1890

Image © Wikimedia Commons / Almond Blossom © Vincent van Gogh 189010. Almond Blossom by Vincent van Gogh

Finally, taking tenth place is van Gogh’s Almond Blossom, painted in 1890 to celebrate the birth of his nephew. Its pale blue sky and delicate white blooms are lighter, calmer, and more hopeful than many of his works. The almond tree, one of the first to flower each spring, became a symbol of renewal, purity, and optimism, revealing an optimistic moment within the context of the artist’s mental health. The painting’s flattened branches set against the clear sky reveal his love of Japanese ukiyo-e prints, whose contour and decorative restraint he suffused into this artwork.

In Brazil, it resonates as a portrait of tenderness. Admirers found peace in its colours, or loved the thought of its creation as a gift. The 100% female response suggests a connection to its softness and emotional symbolism, and it stands as a reminder that even amid personal struggle, beauty can be offered as a blessing.

@ MyArtBroker

@ MyArtBrokerBrazil’s Top Ten artworks reveal a population fiercely protective of its cultural heritage whilst also deeply appreciative of global masterpieces. In Abaporu, Brazilians see a mirror of themselves and a challenge to reclaim what is theirs, whereas in European classics, they find timeless beauty reimagined through personal memory. Across generations and genders, these works prove that ownership is about connection to history, identity, and emotional landscapes.