Campbell's Soup, Soup I, Pepper Pot (F. & S. II.51) © Andy Warhol 1969

Campbell's Soup, Soup I, Pepper Pot (F. & S. II.51) © Andy Warhol 1969

Interested in buying or selling

Andy Warhol?

Andy Warhol

493 works

Elevated from household staple to cult status by Andy Warhol's prints, the Campbell's Soup Cans have come to represent the artist's lifelong fascination with consumerism and advertisement.

To learn more about the iconic series, see our 10 facts here:

Warhol originally wanted to make a comic book inspired series

Campbell’s Soup I, Green Pea (F. & S. II.50) © Andy Warhol 1964

Campbell’s Soup I, Green Pea (F. & S. II.50) © Andy Warhol 1964This concept was, however, already being pioneered by fellow Pop Art kingpin, Roy Lichtenstein.

Looking for a new idea, the story goes that Warhol turned to his friend and advisor Muriel Latow who suggested that he paint Campbell’s soup cans instead. According to his biographer Blake Gopnik, Warhol is supposed to have said “The cartoon paintings…it’s too late, I’ve got to do something that really will have a lot of impact, that will be different enough from Lichtenstein.”

Latow purportedly told him “You’ve got to find something that’s recognisable to almost everybody, something you see every day that everybody would recognise. Something like a can of Campbell’s Soup.”

Did Andy Warhol eat soup?

Image © Andy Warhol, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons / Artworks © Andy Warhol 1969

Image © Andy Warhol, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons / Artworks © Andy Warhol 1969Warhol ate a lot of soup, claiming to have had Campbell’s soup for lunch everyday for decades.

Before he became famous for repetition in his artworks, Warhol was attracted to repetition in his personal life and appearance. By choosing to wear a daily uniform of a white wig, glasses and polo neck jumper Warhol ensured his look became as iconic as his artworks.

And it wasn’t just his personal style that embraced repetition, even his eating habits mirrored his art. Speaking of his choice of Campbell’s Soup as a subject, the artist remarked, “I used to drink it. I used to have the same lunch every day, for 20 years, I guess, the same thing over and over again.”

What was the first Campbell’s Soup Can flavour?

Image © Public Domain / Ad for Campbell's Tomato Soup, 1927

Image © Public Domain / Ad for Campbell's Tomato Soup, 1927Tomato was the first flavour made by Campbell’s and it soon became a best-selling product. For Warhol this flavour – and its iconic red colour – encapsulated the nostalgia and mundanity associated with the soup brand and he chose it as a starting point for his paintings.

By 1969 the soup cans had become so synonymous with Pop Art and its chief proponent that legendary art director George Lois decided to put Warhol on the cover of the May issue of Esquire magazine, drowning in a tin of Campbell’s tomato soup.

Recreating the Campbell's soup labels took Warhol almost a year

Campbell’s Soup II, Tomato Beef Noodle O’s, (F. & S. II.61) © Andy Warhol 1969

Campbell’s Soup II, Tomato Beef Noodle O’s, (F. & S. II.61) © Andy Warhol 1969Warhol’s first paintings of the cans were painstaking reproductions of the labels based on enlarged photographs taken by a friend. According to Gopnik, he spent almost a year recreating the labels onto canvases, in order to make the paintings as close to the mechanically reproduced packaging as possible.

He wanted it to look as if the cans had been taken directly from the supermarket shelves and placed on the wall. In this way he went one step further than Duchamp – who took everyday objects out of their usual context and called them art – and also harkened back to the long tradition of trompe l’oeil in Western art.

How many Campbell’s Soup Cans did Warhol make?

Image © paurian via Flickr, CC BY 2.0 / 32 Campbell's Soup Cans © Andy Warhol 1962

Image © paurian via Flickr, CC BY 2.0 / 32 Campbell's Soup Cans © Andy Warhol 1962Warhol created a series of 32 painted cans, which were originally exhibited at Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles in 1962. The canvases depicted all the soups offered by the brand, from Vegetable Made with Beef Stock to Chicken ‘N Dumplings and everything in between. Rather than being hung on the wall, the paintings were placed on shelves, originally adopted as a solution for ensuring they were all level by curator Irving Blum.

However the shelves quickly took on a different – and very apt – meaning, recalling the stacked displays used by supermarkets and reflecting the artist’s fascination with consumerism. “Cans sit on shelves,” Warhol later said about the installation. “Why not?”

What was the reception to Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans?

Campbell’s Soup II, Chicken ’n Dumplings (F. & S. II.58) © Andy Warhol 1969

Campbell’s Soup II, Chicken ’n Dumplings (F. & S. II.58) © Andy Warhol 1969While Blum and Warhol had high hopes for the show it was not the initial success they had dreamed of. Many critics seized the opportunity to point fun at the idea and its admirers with one stating “This young ‘artist’ is either a soft-headed fool or a hard-headed charlatan,” while a cartoon ran in the Los Angeles Times showing one art lover saying to the other: “Frankly, the cream of asparagus does nothing for me, but the terrifying intensity of the chicken noodle gives me a real Zen feeling.”

Meanwhile a rival gallerist decided to show up Warhol and Blum by displaying a selection of tins of Campbell’s Soup in his window accompanied by a sign that read, “Do Not Be Misled. Get the Original. Our Low Price – Two for 33 Cents.” Little did they know this show would launch Warhol’s career and eventually turn him into a household name to rival Campbell’s.

A full set of Campbell’s Soup Cans can be worth millions

Image © Sarah Ross via Creative Commons

Image © Sarah Ross via Creative CommonsIn the end Blum managed to sell five painting from the series – including one to Dennis Hopper. However he ended up buying these back and paying US$1000 to Warhol in order to keep the set together. This turned out to be a canny move on Blum’s part; in 1996, when Warhol had become a firmly established figure in the canon of American art, the Museum of Modern Art in New York offered Blum around US$15 million for the full set of 32 paintings.

Campbell’s Soup Cans helped to launch Warhol’s Factory

Image © SixSigma, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons / Soup Cans © Andy Warhol

Image © SixSigma, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons / Soup Cans © Andy WarholAs critics and public alike began warming to Warhol’s daring introduction of commercialism to the world of art, the artist was already thinking of new ways to make his work closer to the manufacturing methods of modern packaging and advertising.

As he famously claimed, ‘I want to be a machine’, and in a way he achieved this by his adoption of the silkscreen technique and the establishment of his ‘Factory’, a large studio where he could churn out hundreds of prints in a day.

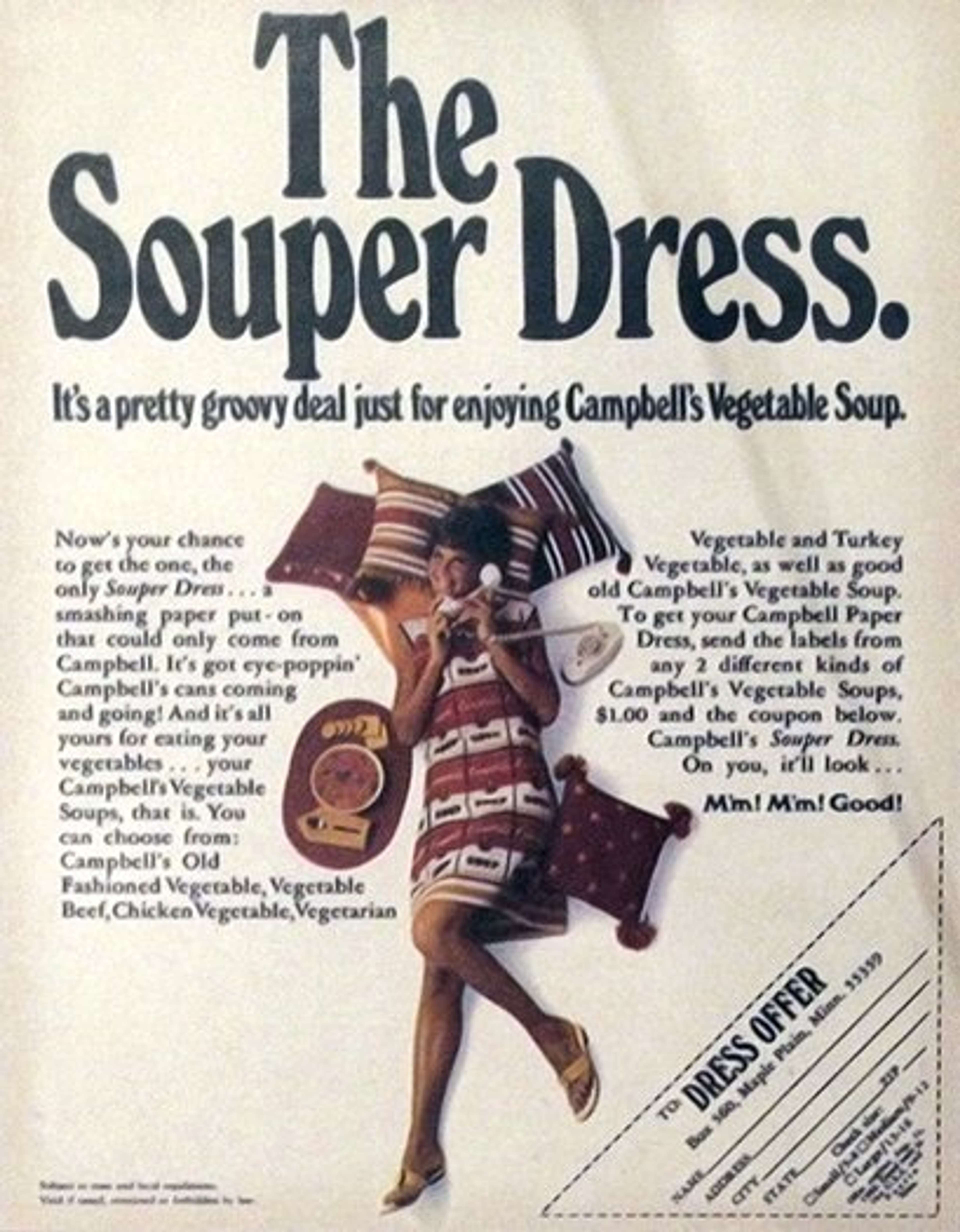

Campbell’s teamed up with Warhol to create Soup Can dresses and tins

The Souper Dress © (CC) Thomas Cizauskas

The Souper Dress © (CC) Thomas Cizauskas As well as producing prints Warhol turned his soup can labels into paper dresses that were worn by the most fashionable New Yorkers to gallery openings and other high profile social events. Soon Campbell’s caught wind of the incredible PR gift Warhol had given them and began producing the dresses themselves, complete with an adjustable hemline.

Later the brand would go on to issue further collaborations with Warhol and his estate including a limited edition series of tins released in the early 2000s in recognisable Warhol colourways, each priced at just 75 cents.

Warhol’s Soup Cans may have been among his personal favourites

Campbell's Soup II, Vegetarian Vegetable (F. & S. II.56) © Andy Warhol 1969

Campbell's Soup II, Vegetarian Vegetable (F. & S. II.56) © Andy Warhol 1969The artist kept adding to the series for years after his initial success. “I should have just done the Campbell’s Soups and kept on doing them…” he is reported to have said, “because everybody only does one painting anyway.” Today the iconic label design and its various Warholian interpretations continue to appear across the worlds of fashion and advertising as well as art, encapsulating the lasting appeal of Pop Art.