Red Celia © David Hockney 1984

Red Celia © David Hockney 1984

David Hockney

653 works

David Hockney’s journey as a printmaker began in 1954, when he was just 16 and studying at Bradford College of Art. His first lithographs introduced him to the process in which images are drawn directly onto a flat stone or plate and printed from that surface. The technique’s emphasis on line, touch and immediacy suited Hockney’s natural strengths as a draughtsman and became his entry point into graphic art. While he would later explore etching, photocollage and digital media, lithography retained a foundational role in his printmaking practice and shaped the direction of his early graphic work.

What is Lithography and Why Did It Suit Hockney?

Lithography is a printmaking technique based on the principle that oil and water do not mix. The artist draws an image with a greasy crayon or ink onto a smoothed limestone or metal plate. The stone is then chemically treated, dampened with water, and rolled with oil-based ink which adheres only to the greasy drawing. Finally, paper is pressed to the stone to transfer the inked drawing in reverse, producing the print. Lithography is planographic, meaning the printing surface is flat, which allows the artist to draw with a natural freedom, almost as if working directly on paper.

Lithography allowed Hockney to capture his spontaneous line work and tonal sketches with ease, preserving the characteristics of his drawings. Moreover, lithography’s capacity for subtle shading and layering of colours aligned with Hockney’s preference for colour and pattern. The medium’s directness and versatility encouraged his natural drawing process, meaning lithography became a fertile ground for Hockney’s burgeoning creativity.

Hockney in Bradford

When Hockney first encountered lithography at the Bradford School of Art, subjects were drawn directly from his immediate surroundings. Woman with a Sewing Machine (1954) portrays his mother Laura seated in the family home, the composition already hinting at Hockney’s lifelong fascination with interiors, everyday ritual, and the rhythms of ordinary life. The most ambitious of these Bradford prints is Fish and Chip Shop (1954), depicting a local shop interior with staff behind the counter and Hockney himself waiting for food. Warm and gently humorous, it transforms a familiar working-class setting into a scene finding richness in the mundane. These early lithographs reveal a draughtsman already turning personal experience into art through printmaking.

Hockney's Early Subject Matter and Storytelling

Beyond his domestic and local scenes, Hockney’s earliest lithographs already show him testing how much meaning a simplified image can carry. In Self-Portrait (1954), one of his first lithographs at Bradford, Hockney presents himself frontally, arms folded, glasses fixed firmly on the viewer. The image is drawn almost entirely in clear, confident lines, with very little shading. Even so, it projects a strong sense of confidence and self-awareness. Rather than offering a subtle psychological portrait, it functions as a statement from the young artist, presenting himself directly to the viewer.

Other lithographs from 1954–55 show the same shallow space and tightly controlled compositions. Figures sit close to the surface of the image, while backgrounds are stripped back to a few structural lines or shapes. This flattening is a deliberate decision, allowing Hockney to focus on close observation, gesture, and visual rhythm rather than on creating depth.

Within this pared-back approach, Hockney already begins to hint at narrative. Meaning comes from how figures stand, how close they are to one another, and what their relationships seem to be, rather than from overt action. Even at this early stage, he is alert to the way images can suggest social roles, identity, or tension. These ideas would soon be pushed further at the Royal College of Art, where lithography and etching became tools for more explicit storytelling and satire. These early lithographs mark the emergence of a graphic language built on precise line and narrative suggestion – an approach that would remain central to Hockney’s work across both printmaking and painting.

Lithography at the Royal College of Art

When Hockney moved to the Royal College of Art in 1959, his printmaking practice expanded rapidly. While etching became the dominant technique during these years, lithography continued to play an important supporting role in shaping his thinking. The RCA encouraged technical experimentation, and Hockney moved fluently between processes, allowing ideas developed in one medium to inform another. Lithography’s emphasis on drawing, flatness, and direct mark-making reinforced his instinctive approach to drawing, even as he explored the more intricate possibilities of intaglio.

You can see this overlap between techniques in Hockney’s early 1960s prints, even when he was no longer working directly in lithography. In works such as A Rake’s Progress (1961–63), the images are built around clear outlines, flattened space, and readable scenes. Figures are arranged so the viewer can quickly understand what is happening, rather than being lost in detail. This approach reflects the habits Hockney developed through lithography, where drawing clearly and directly is essential.

Even when he combined images with written words, as in Myself and My Heroes (1961), the text functions as part of the image rather than as explanation. These prints show that lithography helped shape how he used line, space, and storytelling across different print techniques as he explored how to represent himself, his experiences, and the world around him.

Hockney’s Later Lithographs

Although lithography first entered Hockney’s practice when he was a student, he never abandoned the medium. Instead, he returned to it at key moments across his career, using it alongside etching, photography, and later digital tools to rethink how images are constructed and read. By the late 1960s and 1970s, lithography had become a space for greater play around colour, framing, and the relationship between image and surface.

Works such as Pool Made with Paper and Blue Ink for Book (1980) demonstrate how Hockney adapted lithography to suit his evolving visual language. Here, colour and open space dominate, yet the medium’s defining qualities of clarity, immediacy, and the direct translation of drawing into print remain central. Lithography allowed Hockney to explore repetition and variation, testing how small shifts in colour or composition could alter the mood of an image, a concern that echoes his early interest in structure and visual rhythm.

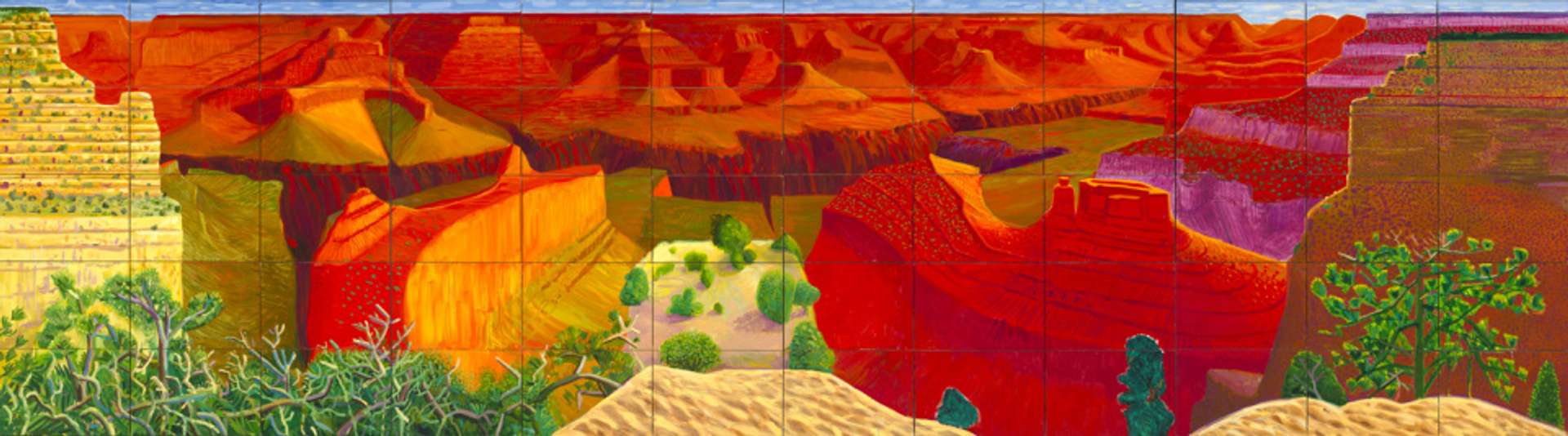

From the 1980s onward, lithography also became a means of revisiting established motifs. Portraits such as Red Celia (1984) show how the medium could support bolder colour and simplified forms while retaining a distinctness rooted in drawing. These later lithographs are more expansive than the Bradford works, yet they rely on the same fundamentals, reinforcing Hockney’s enduring interest in how images communicate clearly and immediately.

Hockney’s lithographs show how lithography provided a consistent framework for exploring line, space, repetition, and clarity. The discipline of drawing directly onto stone shaped his understanding of how images communicate, an approach that carried across his later paintings, photography, and digital media.