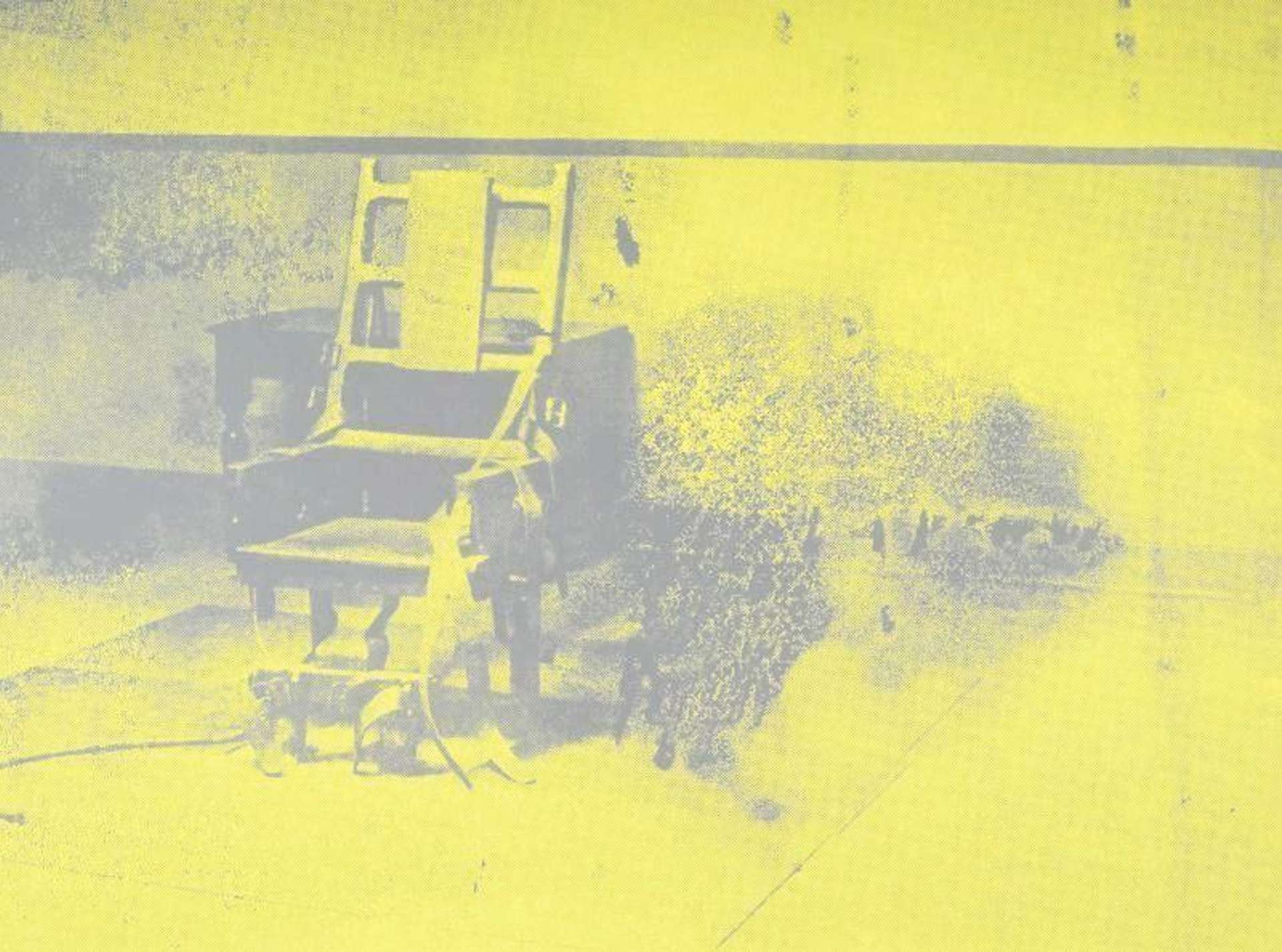

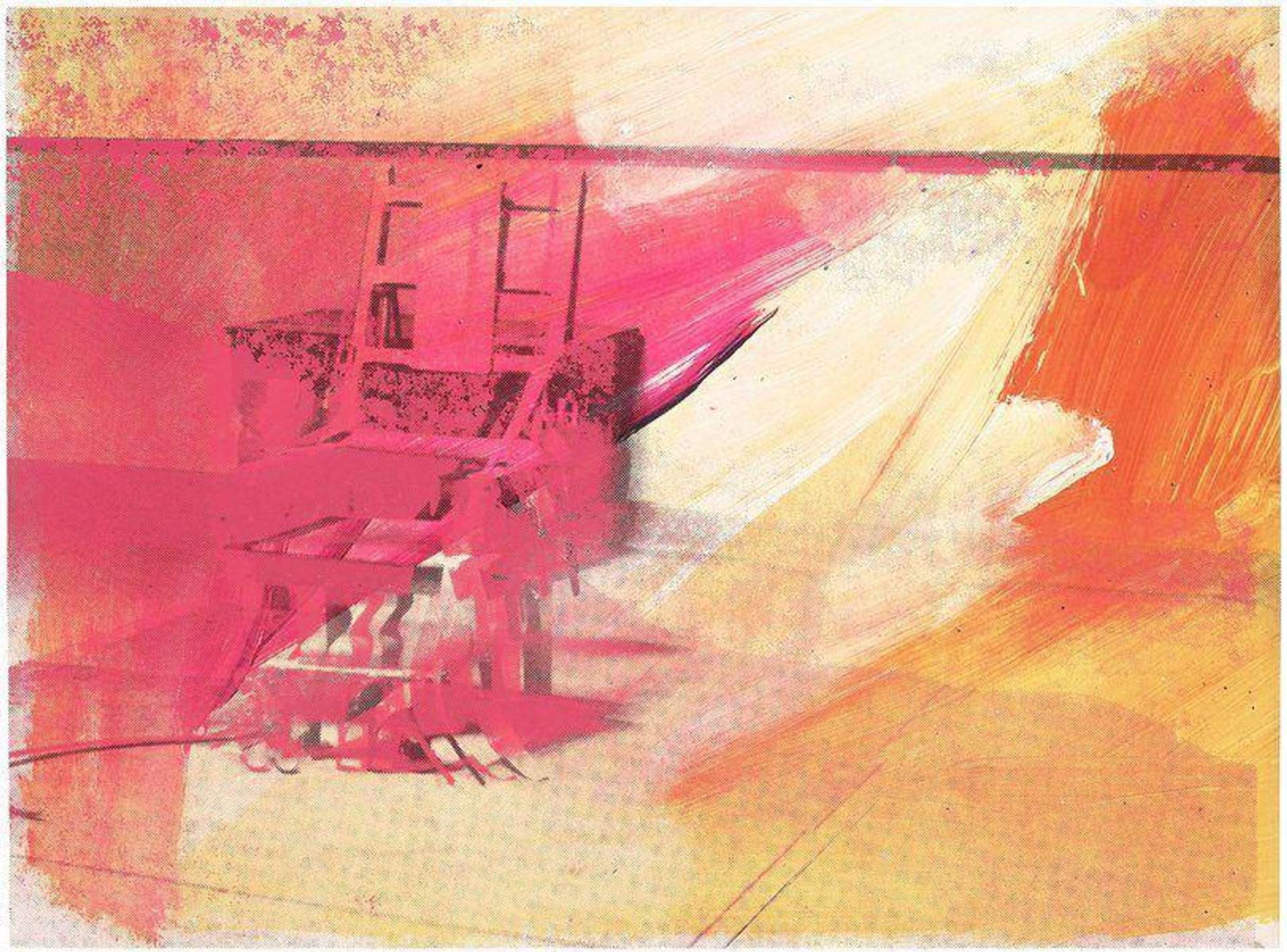

Electric Chair (F & S 11.83) © Andy Warhol 1971

Electric Chair (F & S 11.83) © Andy Warhol 1971Live TradingFloor

Read Chapter Four of Richard Polsky’s mini series on the world of Andy Warhol authentication.

Chapter 4

When I was hired to authenticate Alice Cooper’s Little Electric Chair, the first thing I did was take stock of what was already known about the series. Although the Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné listed exactly fifty examples, I knew for a fact there were more genuine ones out there. The reason I knew it was because I had already authenticated a small group which came out of Chicago. They were sold by a disgruntled employee of Andy’s, who allegedly wasn’t paid (or was underpaid), and absconded with them.

One day in 1972, he arrived in Chicago and began peddling them to established members of the art dealing and collecting community. Each canvas was sold for a discounted US$1,500 (Alice’s cost US$2,500). One of the stories to emerge was that one of the buyers organized a dinner, in Andy’s honor, at his home in Chicago. The host brought his green Little Electric Chair to the table to show Andy, along with a pair of scissors, and offered to cut it up if it was a fake. Warhol grinned, “I wouldn’t do that if I were you.”

That was the thing about Andy Warhol; he took the integrity of his work seriously. I was once at the studio of the Los Angeles painter Chuck Arnoldi, when he showed me a classic twenty-four inch Warhol Flowers painting. The multi-colored flowers on a green background had been sliced up, reassembled, and framed under glass.

I said to Chuck, “What’s the story?”

Chuck smirked, “During the 1970s, Warhol visited my studio and I showed him the painting. He took one look at it and cried, ‘That’s not mine!’ He then asked me for a pair of scissors.”

“So you gave it to him?”

“What was I going to do? It was Andy Warhol.”

Besides the “Chicago Group,” the collector Peter Brant owns twelve paintings from the series. Charles Schwab owns a silver one. Other prominent Little Electric Chair owners include: Cy Twombly’s estate, Irving Blum (who exhibited the original group of 32 Campbell’s Soup Can paintings), The Menil Collection, Yale University Art Gallery, Philadelphia Museum of Art, and, of course, the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh.

How to Prove Provenance: Chasing Paperwork

When I took a look at Alice’s red painting for the first time, I quickly determined the image itself was correct. It was obviously made from the same photosilkscreen as the ones which appear in the catalogue raisonné. Also, the dimensions were right, the use of acrylic paint and silkscreen ink was accurate, and the brown linen it was screened onto was consistent with those examples known to be genuine. Within a matter of minutes I was satisfied that the picture, at least visually, was the real deal.

Q: What is provenance and why is it important?

A: Provenance is the proven history of ownership for an art object, including a range of sources—receipts, photographs showing the painting or object in the artist's studio, correspondence between galleries and buyers, collector's inventory records — which is essential in verifying the authenticity and legal ownership of the artwork.

With that in mind, I knew that giving the work my stamp of approval would come down to its provenance. Provenance refers to the painting’s backstory. Ideally, it lists all of the previous owners of the work, its exhibition history, and possibly its auction history. If a painting was owned by a prominent collector, exhibited at a major gallery or an important museum, it can add immeasurably to its value. In Alice’s case, the cherry on the cake was the celebrity factor. For example, Liza Minnelli once owned a large collection of Andy Warhol paintings. Many of them depicted her or her mother, Judy Garland. When Liza sold them, buyers paid a premium just for the bragging rights.

Provenance research can be tricky. In a perfect world, you would have a photograph of the artist in his studio standing next to the painting in question. Another credible piece of documentation is an illustration of the work in a gallery or museum exhibition catalog. For an early Andy Warhol painting, these scenarios are closely followed by a label on the back of the painting announcing it came from the Ferus Gallery, Stable Gallery, Leo Castelli Gallery, or Galerie Ileana Sonnabend — his key dealers during the 1960s (these days even labels are faked). But barring the above outcomes, you often have to dig deep. Given Alice’s painting came directly from the Warhol Factory, with no paperwork, I had my work cut out for me.

After much thought, I decided to assemble a timeline for Alice’s canvas. Shep Gordon, Alice’s personal manager, set up a conference phone call with Alice. The conversation turned out to be entertaining but a little weak on useful information. Alice’s memory was shaky. It was asking a lot of a rock and roller — who toured and partied heavily in the 1970s — to recall the details from a relatively minor event in his life that took place decades ago. Alice got a kick out of owning the painting, but I sensed it wasn’t all that important to him.

Fortunately, Shep Gordon had a better memory. He was one of those rare individuals you meet in life who make an impression on you. Frankly, I had never heard of him until Ruth Bloom phoned me on his behalf, to authenticate Alice’s painting.

I recall Ruth asking me, “Do you know who Shep Gordon is?

“No, I don’t.”

“Well, there’s a movie about him on Netflix called Supermensch: The Legend of Shep Gordon — you have to see it.”

Image © Sotheby's / Judy Garland © Andy Warhol 1978

Image © Sotheby's / Judy Garland © Andy Warhol 1978They Call Me Supermensch: Shep Gordon

A mensch is a Yiddish word which loosely translated means a good person. A mensch is the sort of guy who calls his mother every Sunday night and always tries to do the right thing. I rented the DVD and sure enough, Shep’s life story was impressive. The guy came from nowhere (actually, Buffalo) and through incredible luck, timing, and business savvy wound up as one of the biggest rock managers in the world. Then he did it all over again when he helped launch the “celebrity chef” movement. But what made Shep the “supermensch” was his compassion for others. Unlike many hardcore businessmen, he never saw deal making as a zero sum game. Instead, he made it a point of doing business so both sides walked away winners.

Not long after I was hired to research Alice’s painting, I received an invitation in the mail to attend a book signing for Shep’s autobiography, They Call Me Supermensch. The book was commissioned by Anthony Bourdain, who had his own imprint with Ecco Press. The event was being hosted by none other than Alice Cooper. It was due to take place in New York at a hip boutique called Shinola Detroit. They were known for luxury goods, including watches, bicycles, and fine leather gloves.

My wife convinced me to fly to New York for the book signing. At the last minute, I invited the artist Bill Kane to join me. Upon landing at Newark, we took a taxi to SoHo, where Bill had booked us into an Airbnb. The spacious loft was gorgeous; too bad it could have been the setting for a Roach Motel commercial (“they check in but they don’t check out”). The good news was our location was only two blocks from the event.

A couple hours later, we walked down to Shinola Detroit. Memories of SoHo’s flourishing art scene during the 1980s flooded back to me. When we walked in, the book signing was in full-swing. Beams of light ricocheted off shiny bicycle fenders. There was a bartender mixing cocktails, flanked by a table stacked with copies of Supermensch. A small crowd of well-wishers were gathered around Shep and Alice. Some of them were record company executives; I recognized an elderly Clive Davis.

I saw a few people wearing white tee-shirts whose blue letters carried the crude message: No Head No Backstage Pass. When I asked someone who was wearing one what it meant, he replied with a laugh, “You’ll see a picture of Shep in his book wearing the same shirt during the 1970s. He decided to cut through all the bullshit with the groupies who wanted to go backstage and meet the performers — by knowing they needed to accommodate him!”

Then he walked over to a table, grabbed a shirt, and said, “Here — have one!”

I waved Bill over and he walked away with a souvenir, too.

As we made our way over to Shep and Alice, Shep called out, “Alice, this is Richard Polsky. He’s the guy who helped us with the Warhol.”

While Bill looked on in bemusement, I greeted Alice, “Hey, great to meet you.”

Alice was slim and of average height, with dyed coal-black hair, and heavy black eyeliner. He was decked out in black leather and sported a medallion around his neck that resembled a gold doubloon. Considering he had just turned seventy, and had endured the rigors of touring for over almost fifty years, he looked pretty darn good.

I was impressed by his sincerity; jaded he was not. It was obvious that the former Vincent Furnier was completely comfortable in his Alice Cooper persona. He had been Alice for so long, that his previous and current lives had completely merged. His striking wife Sheryl Goddard was by his side the entire time we spoke. Just like Alice, she couldn’t have been any nicer. Like the handful of other rock marriages which have endured — such as the late Charlie and Shirley Watts — there was something reassuring about meeting Alice and Sheryl.

I was careful not to overstay my welcome, knowing there were others who wanted to meet him. But I couldn’t resist asking Alice a parting question:

“I don’t know if you remember this, but I once read a story about how you were hanging out at a club in Los Angeles during the 1980s called On the Rox. You were talking to a group of young musicians when all of a sudden Paul McCartney walked in. One of the guys jumped up and yelled, ‘Let’s go say hello to Paul’ and you told him, ‘Sit down! You’re not cool enough to talk to Paul McCartney.”

Alice looked at my quizzically, and said, “I think I remember On the Rox … that could have happened.”

Regardless, I appreciated that he indulged me. Then I spoke to Shep for the first time. Once again, I didn’t expect him to be so modest and easy to talk to. I sensed that one of the keys to his success was how he treated everyone as an equal. I had him sign a book while we talked about what was next for the Warhol painting. A moment later, a photographer stopped by and Bill, Shep, Alice, and I posed for a photo. A few weeks later, I spotted it on the internet, and shook my head in wonder.

As we said our good-byes, I asked Shep, mostly in jest, “So, do I have a coupon with you?”

Shep grinned, “Yes, you have a coupon.”

A coupon was Shep’s way of saying he owed you a favor. If you did Shep a “solid,” then he owed you one in the future — it was like money in the bank. Shep came up with his coupon concept during the mid-1970s when he was trying to break the singer Anne Murray. While she may have had a terrific voice, she lacked street cred with the record buying public. That’s when Shep hit on a stratagem which he referred to as “guilt by association.” He managed to convince John Lennon — who was hanging out at the time with Harry Nilsson at the Troubadour club in West Hollywood — to pose for a photo with Anne Murray. An appreciative Shep Gordon then told John that he had a “coupon with him” (leading me to wonder whether he ever used it). Shep promptly sent the picture to the producers of the popular show Midnight Special, who agreed to have Anne appear on an upcoming broadcast. With that kind of exposure, she broke through and went on to a successful career.

Breaking Bread with Shep Gordon

As I left Shinola Detroit that evening, I felt nothing but gratitude for what just transpired. Though it was certainly fun meeting Alice, I felt I had made a new friend in Shep Gordon. While I use the term loosely, I sensed we would be working together in the future to try and bring Alice’s painting to market. Even for someone with Shep’s extensive business dealings, there was nothing to prepare him for the machinations of the art market. I envisioned signing on as a consultant on the project. I never saw it as a conflict of interest. Rather, I felt my forty-year tenure in the art industry put me in a unique position to advise him on the best way to sell the picture.

Within thirty days of the book signing, I heard from Ruth Bloom looking for advice on how to restore the painting to perfection. It came to light that it had been slightly scuffed many years ago, when it was placed under Plexiglas on top of a coffee table. More significantly, a determination had to be made on how to properly center the image and mount it. That’s because Warhol typically screened his images onto flat sheets of canvas, with plenty of excess fabric surrounding the image. This allowed it to be stretched and stapled onto wooden stretcher bars.

While all of this was going on, I read an amazing article about how a bottle of 2015 Alexander Valley Cabernet Sauvignon — from Shep Gordon’s personal label — sold for a mind-bending US$350,000 (in 2017). Previously, Shep had contracted with The Setting, a boutique winery in Napa, to produce a small number of cases to share with friends. The record-setting bottle sold at a charity auction sponsored by chef Emeril Lagasse’s foundation. Emeril was one of the chefs who Shep helped bring to prominence, in his second act as the catalyst behind the celebrity chef phenomenon. Granted, whoever bought the bottle intentionally overbid to support the charity. But it was still a remarkable event that received a lot of media coverage. When I heard about it, I saw it as a good excuse to give Shep a call and stay in touch.

“Hi, Richard,” said Shep.

“Hey, congratulations on breaking the record for the most expensive bottle of wine ever sold at auction!”

“Yeah, that was something wasn’t it?” he mused.

There was a brief pause.

Then Shep jumped in again, “Would you like a bottle?”

“Are you kidding?”

“I’ll hand you over to my assistant Nancy Meola and you can give her your address,” he said.

Before I could even thank him, he said, “I’ve got to run. Here’s Nancy…”

Sure enough, two days later, the Cabernet arrived via FedEx. I decided to share my good fortune with three other couples — everyone would get to try half-a-glass.

On the night of the big tasting, I carefully decanted and poured the wine. As I did so, my guests made jokes alluding to the decadence of drinking something so absurdly expensive. Though I was far from a wine expert, I savored the distinct notes of blackberry, which grew deeper with each sip. When I poured my wife Kimberly her “rightful share,” a drop accidently went over the side of her glass.

I yelled in jest, “Quick — lick it — that drop’s worth $500!”

Keep reading: 'I Authenticated Andy Warhol'.

Read the previous instalment of the series here.

Richard Polsky is the author of I Bought Andy Warhol and I Sold Andy Warhol (too soon). He currently runs Richard Polsky Art Authentication: www.RichardPolskyart.com