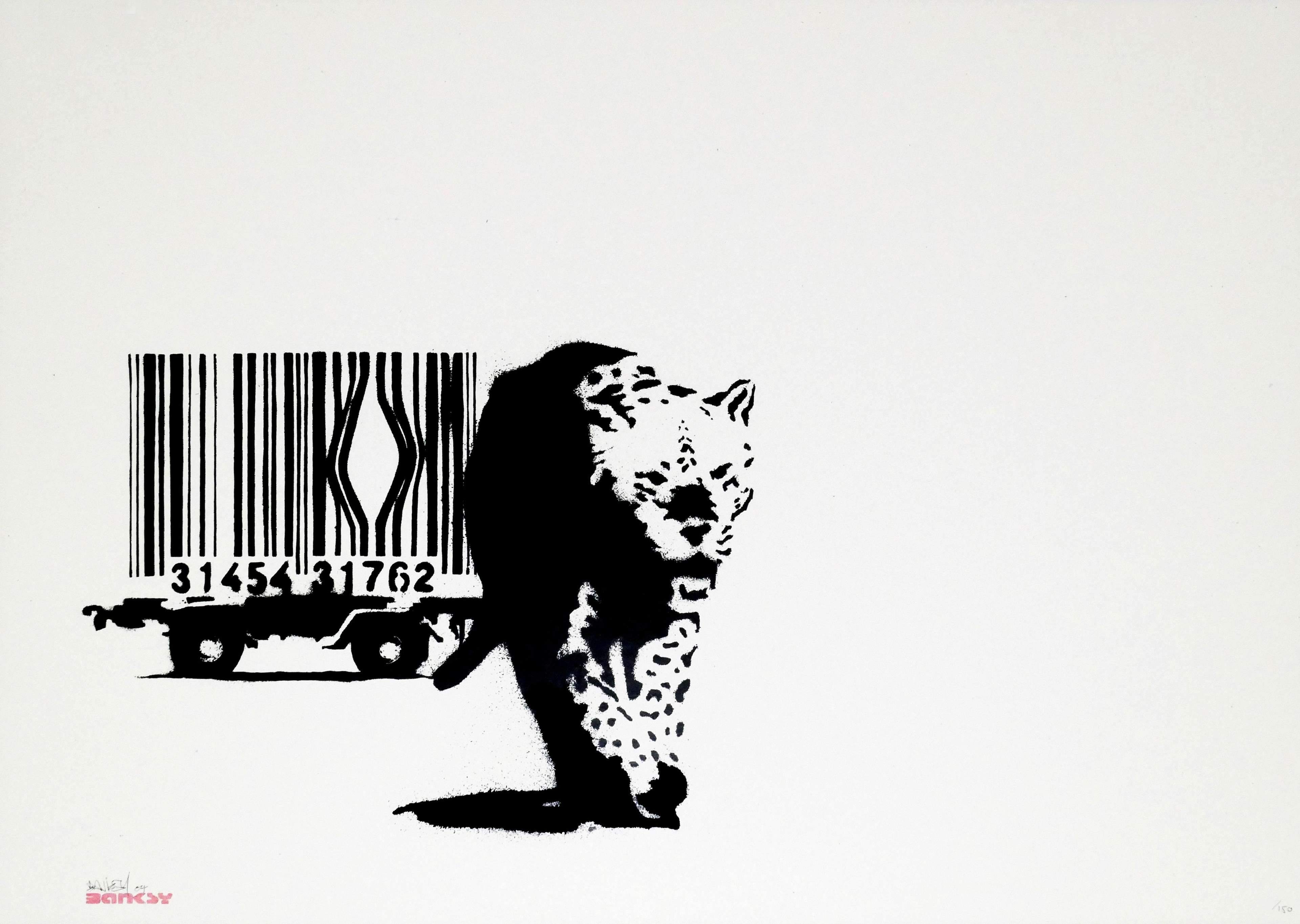

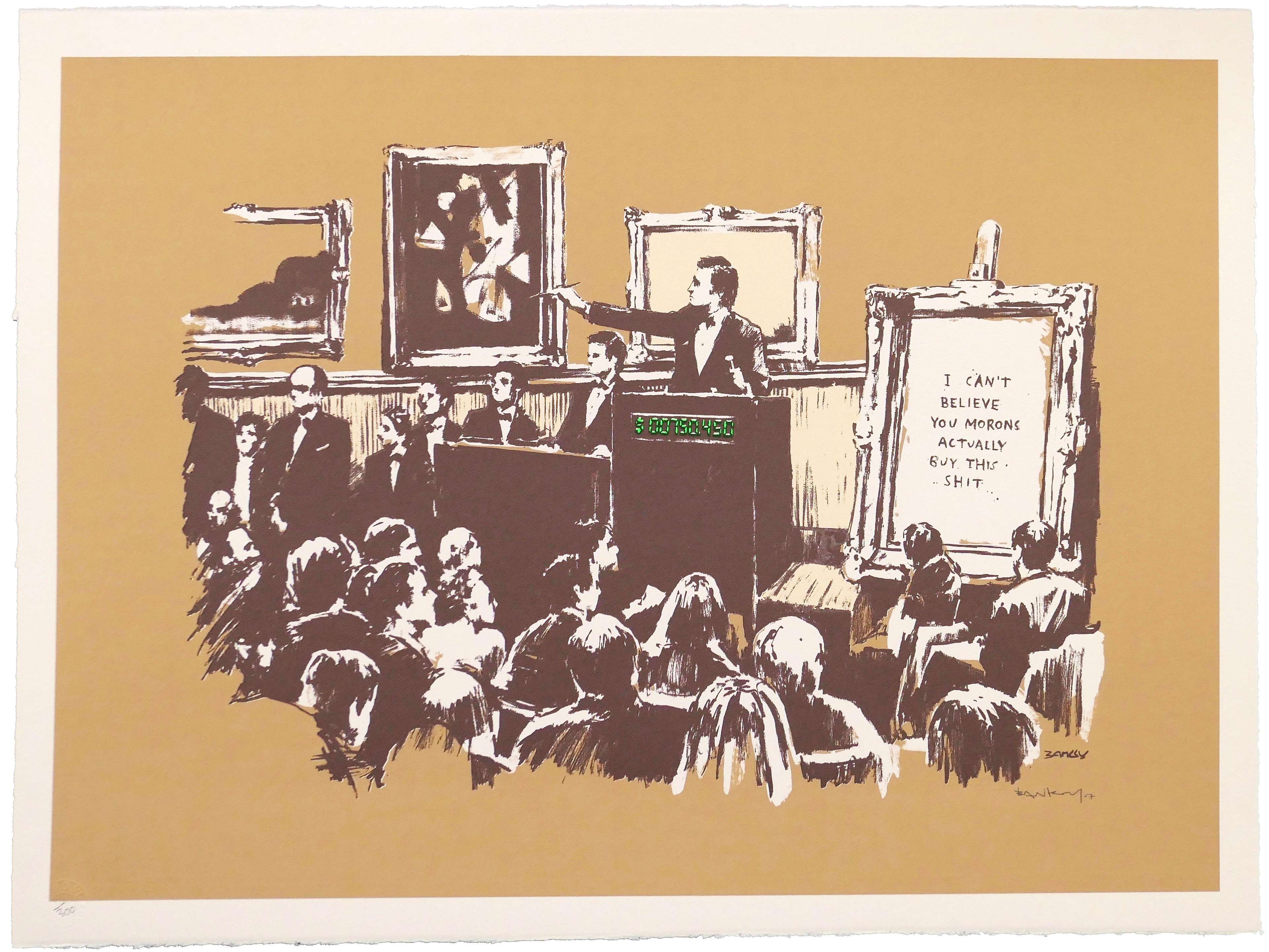

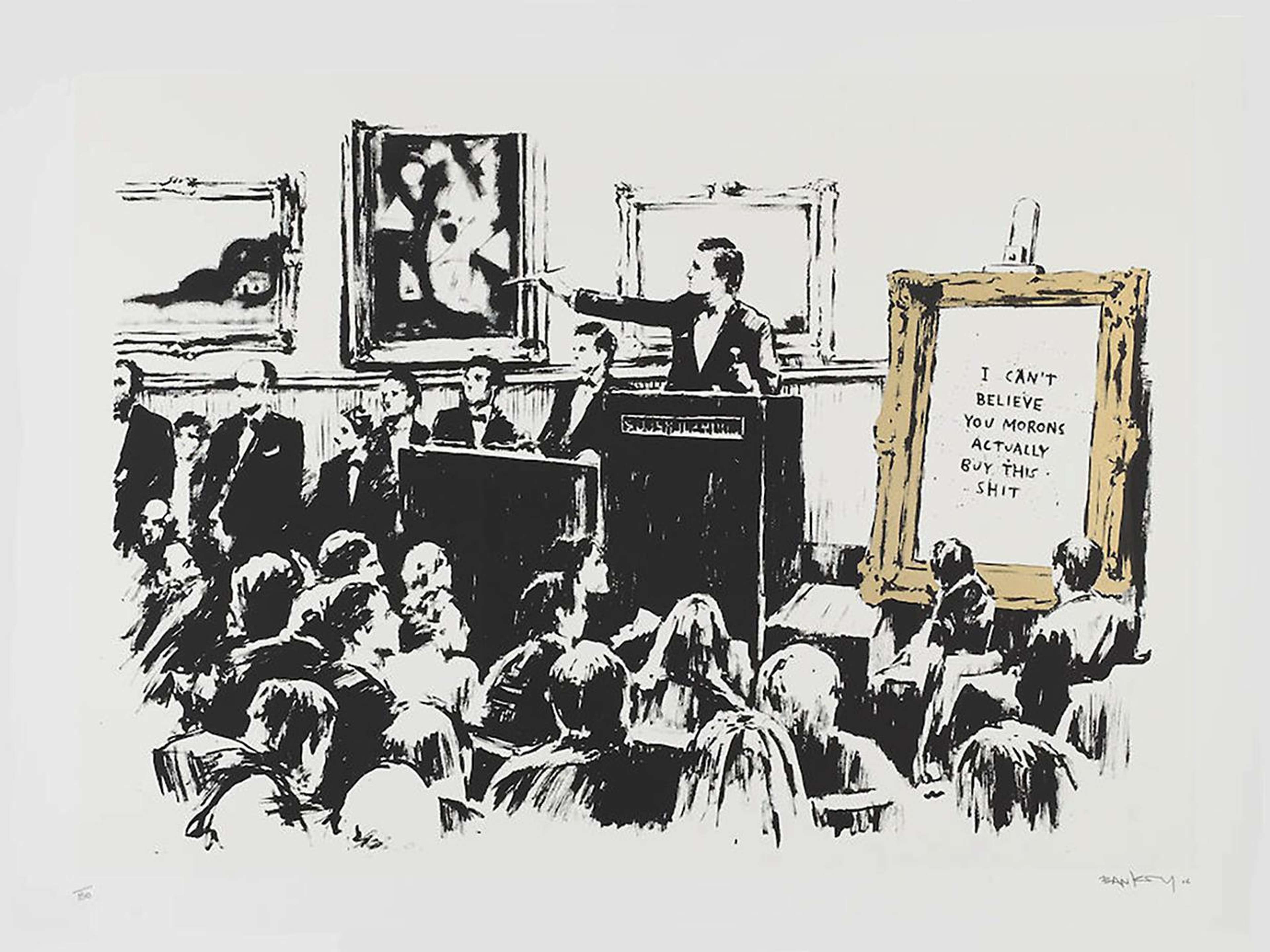

Morons (LA Edition, white) © Banksy 2007

Morons (LA Edition, white) © Banksy 2007Market Reports

The history of art and the history of the art market are inextricably bound. Of course, artisans, artists, and draughtsmen have relied on the sale of their crafts for centuries. However, the history of the art market itself is one which is rather overlooked. When did the ‘art market’ as we know it today truly begin? How has the art market transformed in recent history? And how does the art market influence the value of art itself? Here, we look to the history of the modern art market and its potential future.

What is the Art Market?

Primary Art Market

The primary art market represents the sale of capital which has never been sold before. The primary art market has existed for centuries, as artists received payment for works and commissions directly from their collectors and patrons. Essentially, the primary art market refers to artworks which are coming into the market for the first time.

Secondary Art Market

The secondary art market, on the other hand, represents the re-sale of capital which has been sold at least once before. Whether that sale be through auction houses, private networks, or online trading platforms, the secondary art market deals with artworks which have a sale history.

Though people have certainly been dealing art for a long time, the idea of art as an ‘investment’ is a relatively modern phenomenon. Nowadays, the secondary art market trades colossal amounts of money every month, and buyers are more and more concerned with the potential value growth of their artwork.

Here is a concise history of the art market as we know it, and how we got here:

1960s: Pop Art & The Commercialisation of Art

The advent of Pop Art revolutionised the history of art itself. King of Pop Andy Warhol operated his art practice like a business, creating works inspired by the popular commercial products of his age, and churning out screen prints like a business. It is no coincidence that Warhol named his New York studio the ‘Factory’, and employed assistants here to help him produce more and more sellable art for ever-growing prices. As Warhol himself once remarked: “Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art. Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.”

The art world in its entirety was monetised like never before in the 60s. Gallerist and art dealer Leo Castelli, for example, represented his artists like a business investor. By providing his artists with support and funding, Castelli propelled the likes of Warhol to international acclaim and spurred the value growth of their works during their lifetimes - something rarely achieved previously in art history.

The 60s was, therefore, not only the age of the blockbuster artist, but also of blockbuster art sales. From this decade onwards, art was considered a legitimate ‘investment asset’. The line linking art to capitalism was thus inscribed in indelible ink - never to be erased.

Image © Artsy / Collectors Ethel and Robert Scull with Andy Warhol, George Segal and James Rosenquist © Jack Mitchell 1973

Image © Artsy / Collectors Ethel and Robert Scull with Andy Warhol, George Segal and James Rosenquist © Jack Mitchell 19731970s: The Diversification of Collectibles

Once the seed had been planted in the 60s, investors increasingly saw art as an alternative asset to be capitalised upon. Throughout the 70s, the secondary art market underwent vast expansion thanks to this new understanding of art in relation to economics. So powerful was the link between art and capital that, in 1971, Robert Projansky penned “The Artist's Contract”, which protected artist's ownership and royalties to their work.

In 1973, a landmark auction took place at Parke Benet (now known as Sotheby's), which is remembered as “The Scull Auction”. Robert and Ethel Scull, who were prolific collectors of contemporary art in the 1960s, decided to sell their collection. Their 50 lots were sold with a high rate of return, testifying to the high value attached to contemporary art and the growing strength of the art market itself. This blockbuster auction is considered one of the defining moments in modern art market history, and paved the way for the commercial art market as we know it today.

In 1974, the British Rail Pension Fund began investing in art, allocating £40 million of their holdings to art investment. This large-scale operation was conducted through Sotheby's, who offered British Rail “free” advice on their investments. The state-owned company's decision to invest in art is testament to the increasing trust in art as an alternative asset throughout the decade.

Image © Christie's / Christie's London 1987 - record breaking sale of Van Gogh's Sunflowers for £22.5million

Image © Christie's / Christie's London 1987 - record breaking sale of Van Gogh's Sunflowers for £22.5million1980s: Booming Sales Worldwide

The 80s was a decade characterised by big business and big money. By this point, the art market was truly booming. A thirst for wealth and excess among investors drove art prices higher and higher. Japanese buyers became increasingly attracted to the market in this decade, motivated by rapid economic growth that spurred inflation in real estate, stock prices, and art. For the first time in history, the secondary art market was a global endeavour, and soaring prices showed no sign of relenting regardless of the 1987 stock market crash.

In 1986, a change in U.S. law made it less appealing for wealthy collectors to donate their art to museums and galleries - catalysing a series of big sales. The biggest of these sales was - undoubtedly - the 1987 sale of Van Gogh's Sunflowers at Christie's. As a New York Times correspondent recorded, the crowd at Christie's “could only gasp, applaud and cheer as the opening $8 million bid for the van Gogh was almost quintupled by the two unidentified telephone bidders in the space of 4 minutes 20 seconds.” The winning bid was secured by Japanese fire-insurance company Yasuda, who bought the painting for a record-breaking $39.9 million. This astonishing sale set an auction record, and set a new precedent not only for soaring art prices, but an expectation for spectacle at auction sales.

Image © The Brooklyn Museum / YBAs from the Saatchi Collection

Image © The Brooklyn Museum / YBAs from the Saatchi Collection1990s: Contemporary Art Reigns

Throughout the 90s, auction sales continued to boom as art prices spiralled. This sensationalism in the art market was fuelled even more by the advent of contemporary art, particularly that of the Young British Artists (YBAs). High profile-exhibitions showing the likes of Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin were promoted by the infamous Charles Saatchi. Saatchi's sponsorship of the YBAs meant that they were marketed not merely as artists, but opportunities for collectors to turn a quick and big profit.

2000s: Boom, Crash, and Art Market Resilience

The financial boom in the 2000s spurred exponential growth in the art market once again. Even after the 2008 crash, when Sotheby's stock alone dropped by 83%, the art market bounced back and remained resilient.

Certain factors owing to that resilience included the opening of Tate Modern in 2000, which increased global interest in contemporary art. The likes of Hirst became household names, and were able to sell their art for large figures and with relative ease despite economic downturn. Also, the advent of the internet opened the opportunity for online art sales. This particular factor is the single-most important change in art market history in our age. With corporations like eBay came an easier and infinitely more accessible way to purchase art - something auction houses quickly responded to.

Image © Sotheby's / Auctioneer Oliver Barker holding court over Sotheby's global e-auctions

Image © Sotheby's / Auctioneer Oliver Barker holding court over Sotheby's global e-auctions2010s: The Emergence of Online Art Markets

Thanks to the rapid development of technology, the secondary art market found a long-lasting place on the internet in the 2010s. Not only did auction houses begin conducting their sales live online, but access to information and pricing data became essential for online art market platforms. What had traditionally been thought of as an inaccessible world for many suddenly became infinitely more accessible.

With the touch of a button, you could now view historical art sale results, analytics reports, and even purchase an artwork. The art market was thus opened up to a new generation of collectors who demanded more prior to sale, with a thirst for information and access.

2020s: Into the Age of Market Transparency & Accessibility

As we head forth into this decade, the art market is set to transform even further. In the past five years alone, we have witnessed sweeping social, political and economic change which will shape the future. The COVID-19 pandemic spurred the world to occupy online spaces more than ever before - affecting the art world and its market to this date. A new age of online art collecting has necessitated markets like MyArtBroker, who provide transparency, accessibility and - above all else - information.

Likewise, the world of cryptocurrency and NFTs is an uncertain one - but one which cannot be ignored. With Sotheby's and Christie's dedicating entire auctions to NFTs, the metaverse poses a new frontier for the art market to explore.

One thing, however, is certain: the art market shows no sign of regressing, and the online art market is only getting started.