The Uses, and Misuses, of Price and Value in the Art Market

Pretty Tulips © David Hockney 1969

Pretty Tulips © David Hockney 1969Market Reports

Value is a market mechanism and not as much of a moral question as perhaps the media would have us believe.

By now, everyone agrees on at least one thing: the art market feels strange. Fragile in places, grotesque in others. But where recent commentary starts to lose its footing is in the temptation to turn price into either a moral failure or a cultural lie. It is neither. It is simply a market signal, I agree completely that it is often distorted, frequently misread, but it is not inherently corrupt.

In The Art Newspaper this December, Janelle Zara asks, “how much is art really worth?”, situating today’s pricing anxiety inside a long cycle of boom, bust, and reversal. She notes that, after years of ultra-cheap money and speculative heat, “high prices are under scrutiny as being out of sync with real long-term value.” Dealers, she writes, are quietly becoming more flexible. Even Larry Gagosian concedes: “Like any market, you have to adjust.”

This is a sober and largely accurate diagnosis. But it still frames price as something that somehow ought to behave in line with deeper value, something cultural, historical and even ethical. That’s where I think the category error begins.

Price does not exist to tell us what art means. It exists to tell us what one buyer was willing to pay one seller, on one day, under one set of conditions. That’s it. The trouble starts when we ask it to carry philosophical weight it was never designed to bear.

Eddy Frankel, writing in Artnet after Frida Kahlo’s $54.7m auction record, takes the opposite tack: not that price is misaligned with meaning, but that it is almost entirely irrelevant to it. “This has nothing to do with gender at all,” he writes, “and even less to do with art.” For Frankel, auction records are little more than a grotesque display of surplus capital: “anonymous buyers and sellers speculating and profiteering, using art as a commodity.”

His conclusion is blunt: “I do not care about this auction result, and nor should 99.9 percent of people.”

I understand the emotional impulse behind both positions. But where they converge, quietly, is in treating price as though it is supposed to be a moral instrument. Either it has failed to reflect true value, or it has revealed itself as ethically empty. In practice, it is neither virtuous nor vile. It is just a mechanism.

The danger is not that price exists. The danger is that we confuse it with proof.

The Market Most People Argue About Is Not the Market Most People Use

Most of the media are, in different ways, preoccupied with the very top end of the market: the artists being “IPO-ed,” the $50m trophy works, the political symbolism of record-breaking sales. But this is not where the market actually functions for most participants.

The real market, the one where habits are formed, confidence is built or destroyed, and disappointment is most keenly felt sits far lower. It operates in the £5,000 to £500,000 range. It lives in secondary transactions, repeat buyers, modest gains, occasional losses, and long holding periods. It is slow, often boring, and structurally more - dare I say it - honest.

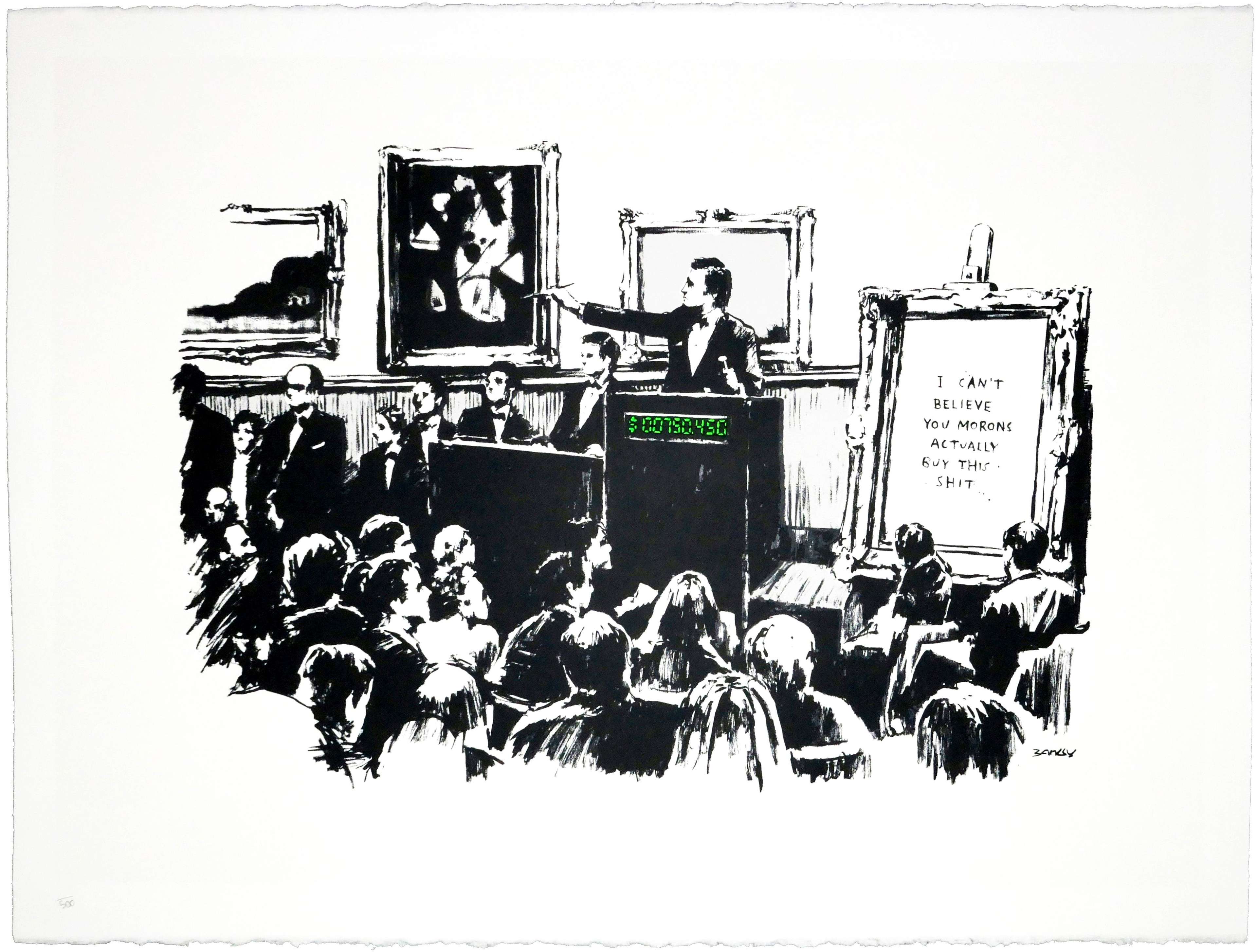

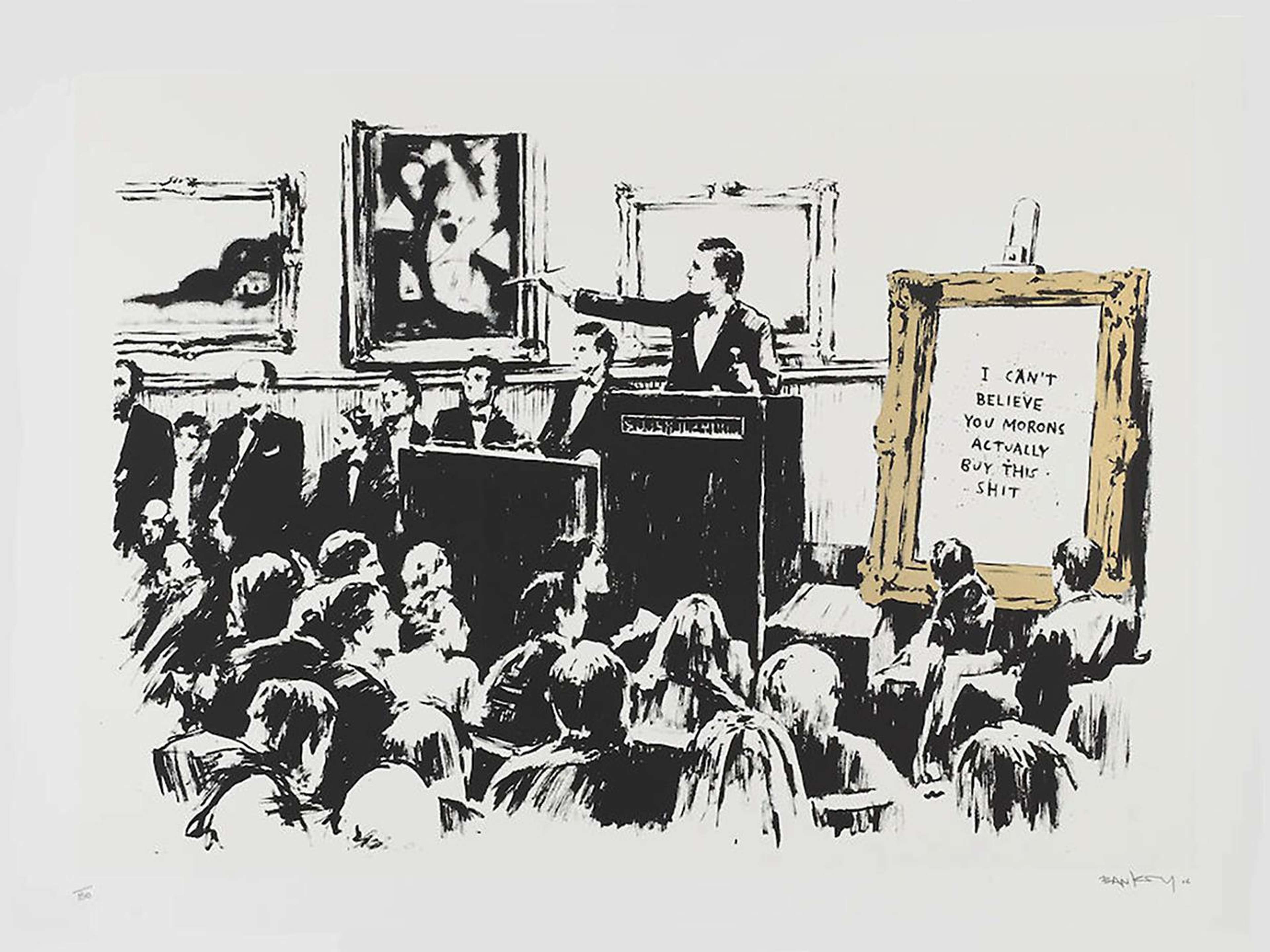

This is why Zara’s observation about “anchoring” is so important. As adviser Mattia Pozzoni puts it in his piece, sellers “keep citing comps from a frothier cycle.” This is not philosophical confusion. It is behavioural finance, pure and simple. People remember peaks. They resist clearance. They interpret yesterday’s outlier as today’s entitlement. Joe Syer made the key point about how we treat Banksy’ market as volatile just because it’s young, and Warhols and Hockneys as steady because it’s old. Bumps look flatter from a distance.

Frankel may be right that a $54.7m Kahlo sale makes no difference to most people’s daily lives. But it does matter in another way: it travels upstream and downstream through the market as narrative distortion. It quietly resets expectations, even for buyers and sellers who will never operate within six zeros of that result.

The top of the market trickles down, no more obviously than in the print markets for artists known for their canvases.

Speculative Auction Results and Valuations Pre-Date Financialisation

Zara traces today’s distortions back to the early 2000s and what Andrea Fraser calls the “emergence of art as a financial asset.” Certainly the language of “ten-times returns,” “IPO artists,” and accelerated expectations belongs unmistakably to the age of finance.

But speculation did not suddenly arrive with hedge funds. Collectors have always speculated. Social signalling, status, and upside have always coexisted with love of objects. What changed was speed, scale, and visibility. The consequences of being wrong now unfold in public, online and in data. This is why disappointment feels louder today. It is not that risk is new.

Where both articles stop just short is in naming the one metric that actually survives cycles: liquidity. A single auction record tells us almost nothing about long-term value. Zara herself acknowledges this through Harmony Murphy’s observation that auction results have “limited accuracy in determining a work’s long-term value,” especially when houses are effectively supporting their own inventory.

What does tell us something is repeated trade. Bid depth. Volume. Cross-market consistency. Works that quietly change hands again and again over ten or twenty years tell us far more about enduring demand than any headline ever could.

This is why prints, so often dismissed as “secondary”, offer one of the clearest windows into real market behaviour. They trade frequently. They reveal patterns. They expose where confidence actually sits, not where it is theatrically announced.

There is a wonderful quote I use frequently from “Auctions and the Price of Art” Ashenfelter, O. and K. Graddy (2002) which says: “The evidence clearly suggests, contrary to the view of the art trade, ‘masterpieces’ underperform the market.”

It’s too true.

The Real Toxic Asset Is Expectation

The most destabilising force in today’s market is not price itself. It is expectation that was never stress-tested.

Collectors were trained to believe upside was normal. Artists were encouraged to see velocity as validation. Galleries learned to speak fluently in momentum. Everyone learned how to quote the highs; very few learned how to model the probabilities. Now, as conditions tighten at the top of the market, reality feels like betrayal. In truth, it is just regression to something more statistically honest.

Frankel is right to recoil from the grotesque theatre of record worship. Zara is right to point out that financial language has overwhelmed artistic conversation. But neither problem is solved by rejecting markets altogether, nor by moralising price. The market is not broken. But the way we talk about it often is.

Price is not a lie. It needs context, probability, and humility wrapped around it. Until we learn to speak about it that way, we will continue to swing between cynicism and fantasy, mistaking both for critique and losing the trust of the next generation of collectors, of those curious but fearful of making mistakes. And the market will keep doing what it has always done: reflect us back to ourselves, with brutal indifference.