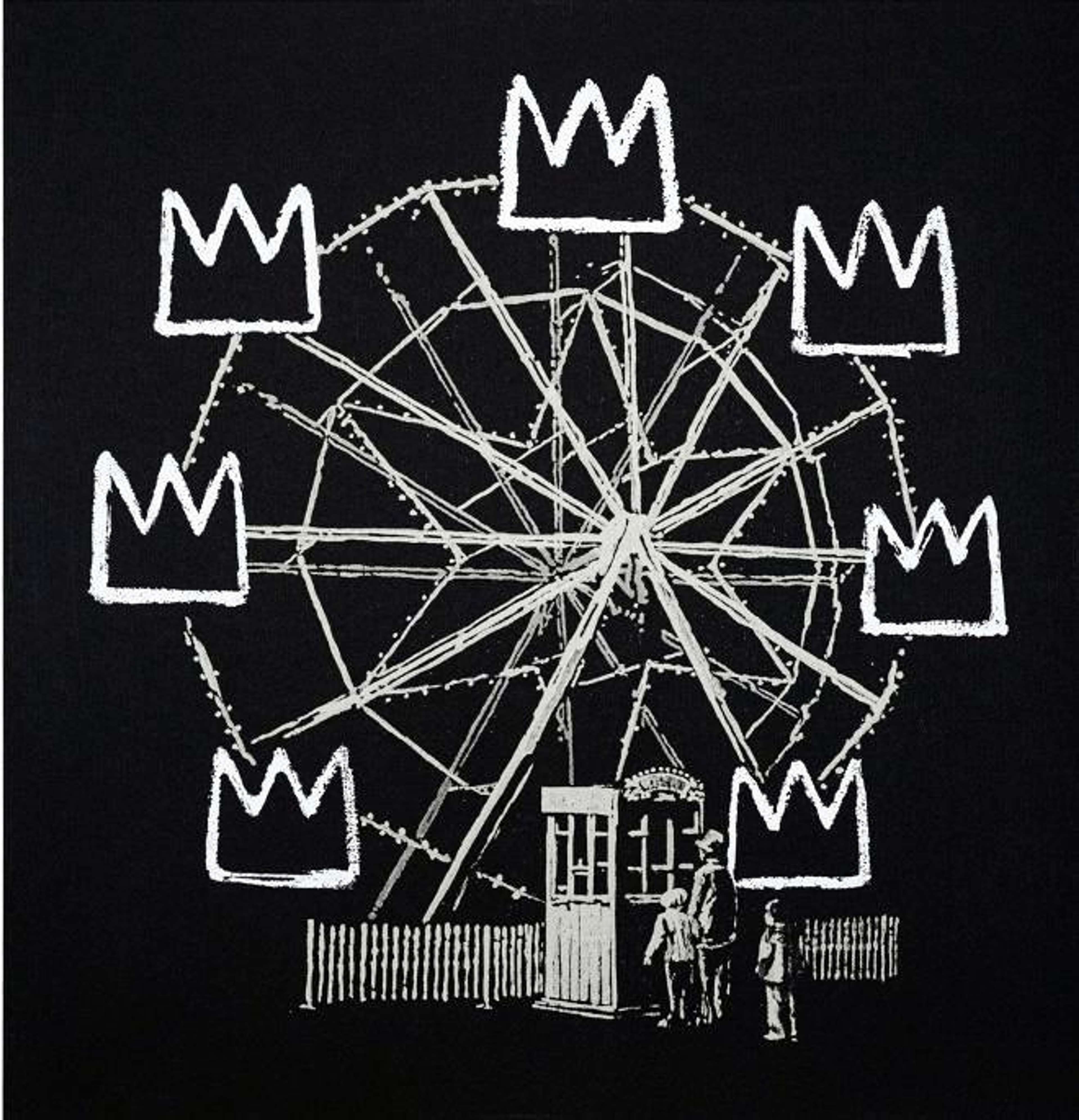

Banksquiat (black) © Banksy 2019

Banksquiat (black) © Banksy 2019

Banksy

270 works

Banksquiat (2019) is Banksy’s ode to Jean-Michel Basquiat and the origins of popularised street art. The monochrome print borrows Basquiat’s iconic crown and imposes it onto a Ferris wheel. By referencing Basquiat, as well as Keith Haring’s subway graffiti, Banksy aligns street art with “high” art while commenting on capitalist commodification, questioning how fame and consumerism recirculate radical imagery.

Banksquiat unites Banksy with the legacy of Jean-Michel Basquiat

Banksquiat (grey) © Banksy 2019

Banksquiat (grey) © Banksy 2019Banksquiat is Banksy’s deliberate attempt to stage a dialogue between two legends of street art. Drawing on Basquiat’s iconic visual language, he traces a clear line from the SAMO-era graffiti of late-1970s New York to his own Bristol-born stencil practice. The work frames street art as a dynamic, democratic field where new images overwrite the old, exploring both homage and competition. By fusing their names into “Banksquiat”, Banksy emphasises continuity as well as influence, channelling the rebellious energy that took Basquiat from street to gallery and redirecting it to keep his own art public, legible, and culturally consequential.

Banksquiat depicts a Ferris wheel made of Basquiat crowns

Back Of The Neck © Jean-Michel Basquiat 1983

Back Of The Neck © Jean-Michel Basquiat 1983Banksquiat depicts a Ferris wheel whose carriages are Basquiat’s three-point crowns, watched by a queue of figures. The image places the public circulating around a symbol long associated with Basquiat’s authority, ambition and Black empowerment, while the fairground setting turns the crown into mass entertainment. This is Banksy’s critique of how traditionally counter-culture graffiti languages get repackaged as commodifiable icons, inviting viewers to question how meaning shifts as symbols change through commercialisation.

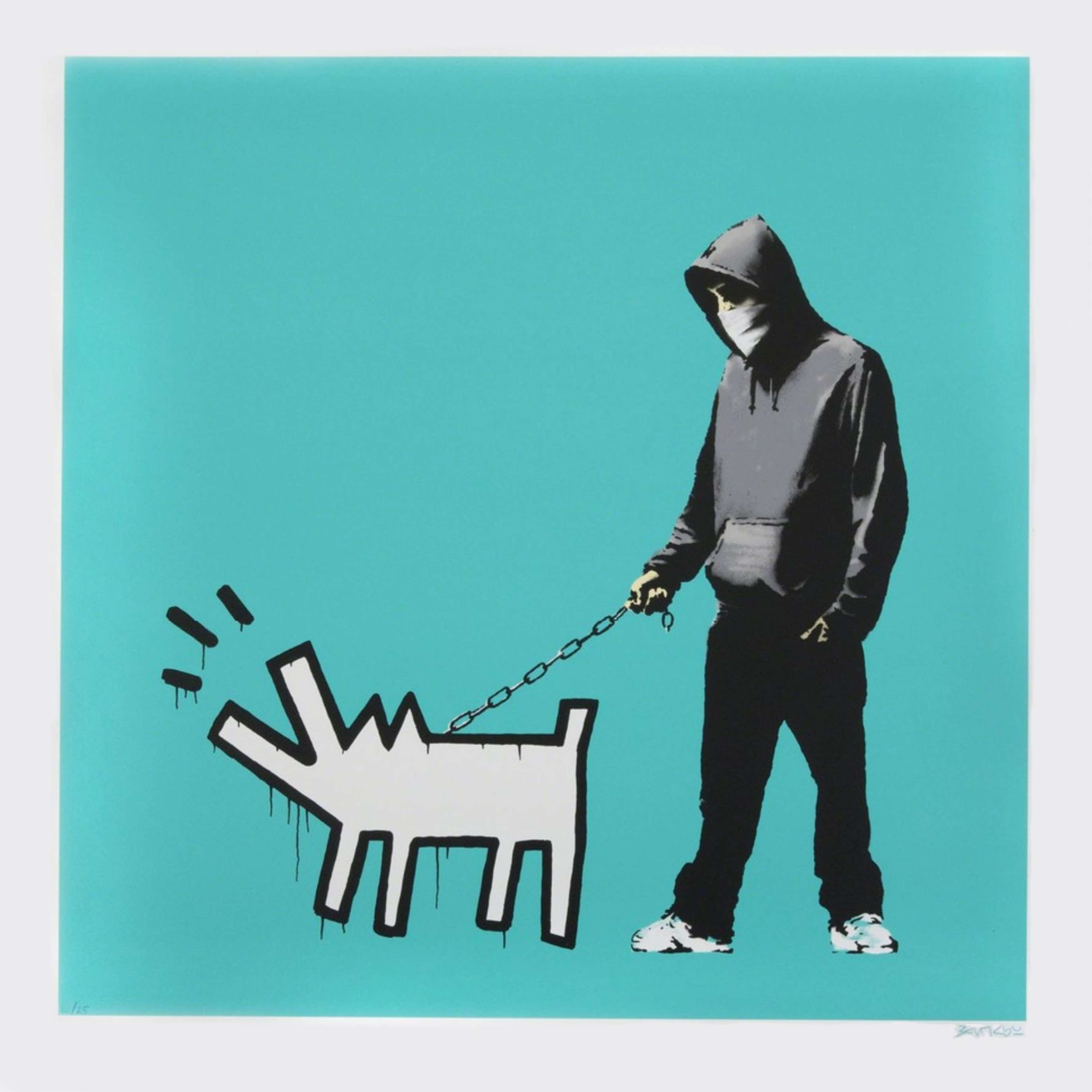

Banksquiat references Keith Haring’s chalk subway drawings

Fight Aids Worldwide © Keith Haring 1990

Fight Aids Worldwide © Keith Haring 1990The grey palette, chalk crowns and black background are an intentional reference to Keith Haring’s early subway drawings, executed in chalk on blank ad panels. Banksy’s prints translate that ephemeral, public-facing urgency into a fixed object while keeping Haring’s style in play. By paying tribute to Basquiat and Haring, Banksy maps a genealogy of street art that treats subways, posters and pavements as galleries. The result is a series that honours the speed, skill, and clarity required for images to be created in an urban landscape.

Banksy uses Banksquiat to critique art commodification and consumerism

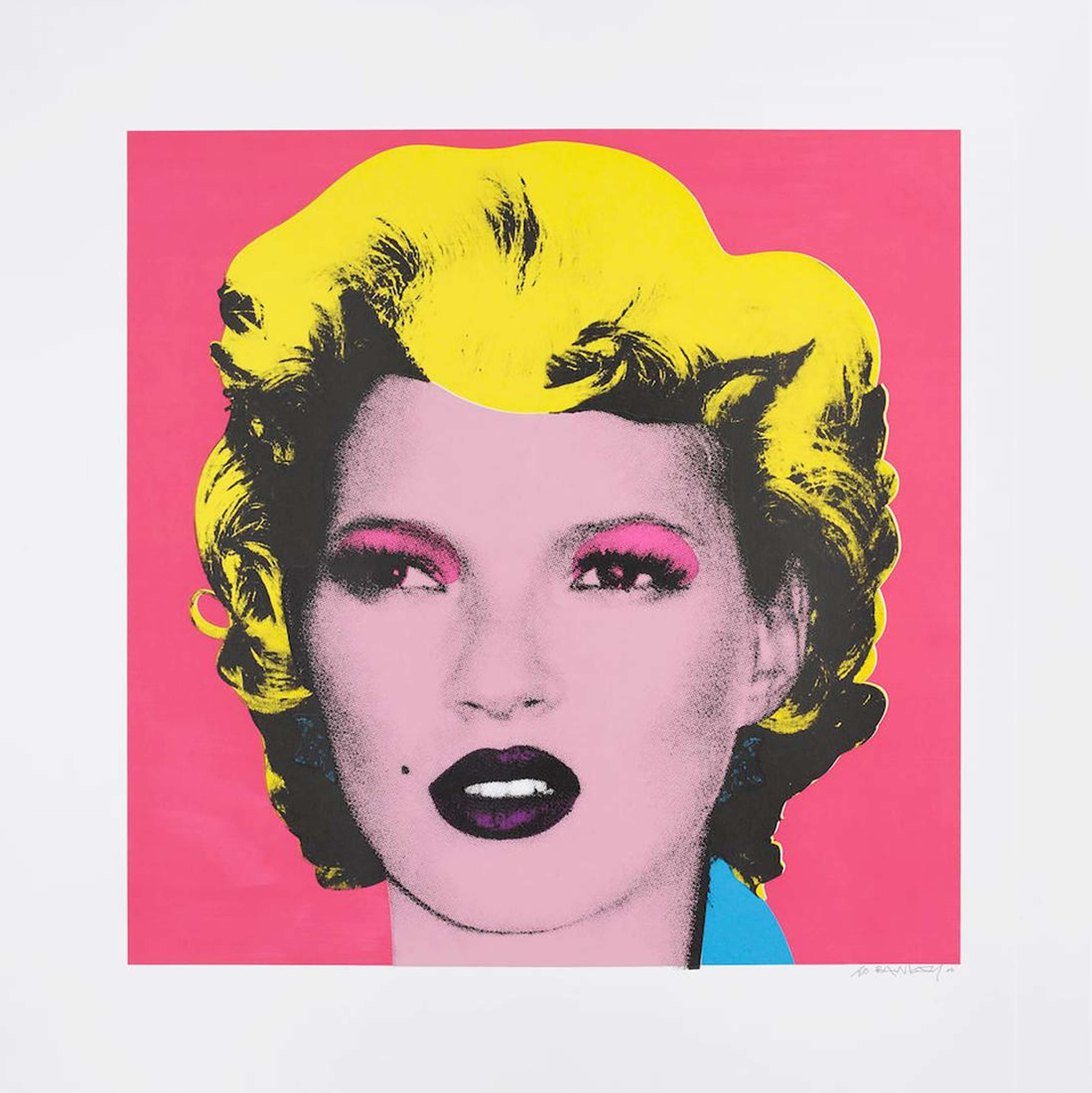

Kate Moss (dark pink) © Banksy 2005

Kate Moss (dark pink) © Banksy 2005Banksquiat also serves as a satirical commentary on how radical imagery gets monetised. The endless wheel signifies capitalism’s relentless output, reflecting the way Basquiat’s crowns are appropriated onto T-shirts, ad campaigns and luxury branding. However, Banksy’s series criticises “relentless commodification” while knowingly adding to the cycle, exposing how critique itself can be absorbed by the market. Banksquiat insists that making art truly public often means multiplying it, even if reproduction challenges the politics that gave the image its meaning.

Gross Domestic Product launched Banksquiat in 2019

Choose Your Weapon (turquoise) © Banksy 2010

Choose Your Weapon (turquoise) © Banksy 2010Banksquiat debuted through Banksy’s pop-up “homewares” brand, Gross Domestic Product, which opened as a Croydon showroom in October 2019 to trial an online release. GDP mocked the idea of a traditional retail experience while also addressing a real trademark dispute over Banksy’s name. Instead of allowing people to buy items directly, Banksy set up a lottery system for buyers, turning the act of shopping into part of the artwork itself. This unconventional approach exposed how value in contemporary art is shaped by demand, scarcity, and legal control. By releasing Banksquiat through Gross Domestic Product, Banksy made the artwork’s message about commodification part of its very method of sale.

Banksquiat reveals Banksy’s recurring fascination with authorship and anonymity

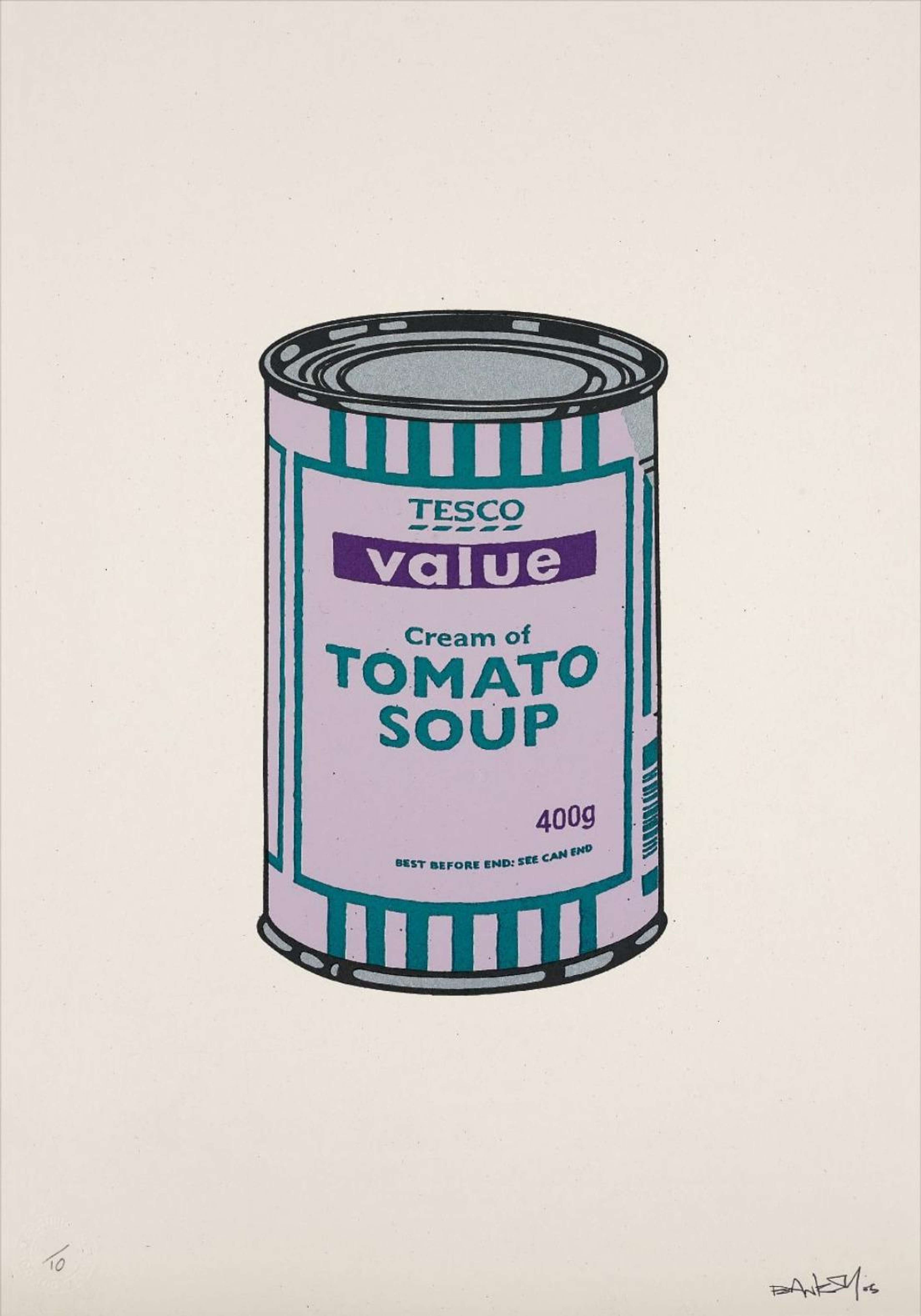

Soup Can (lilac, emerald and purple) © Banksy 2005

Soup Can (lilac, emerald and purple) © Banksy 2005Banksquiat reflects Banksy’s long-standing preoccupation with the tension between visibility and anonymity in street art. By referencing Basquiat (an artist whose rise transformed graffiti from underground act to global brand) Banksy revisits questions about identity, ownership, and recognition. The crowns that once signified Basquiat’s personal authorship becomes, in Banksquiat, a collective and depersonalised symbol. This mirrors Banksy’s own persona whose power depends on remaining anonymous even as his imagery is instantly recognisable.

Banksy uses Banksquiat to align street art with “high” art

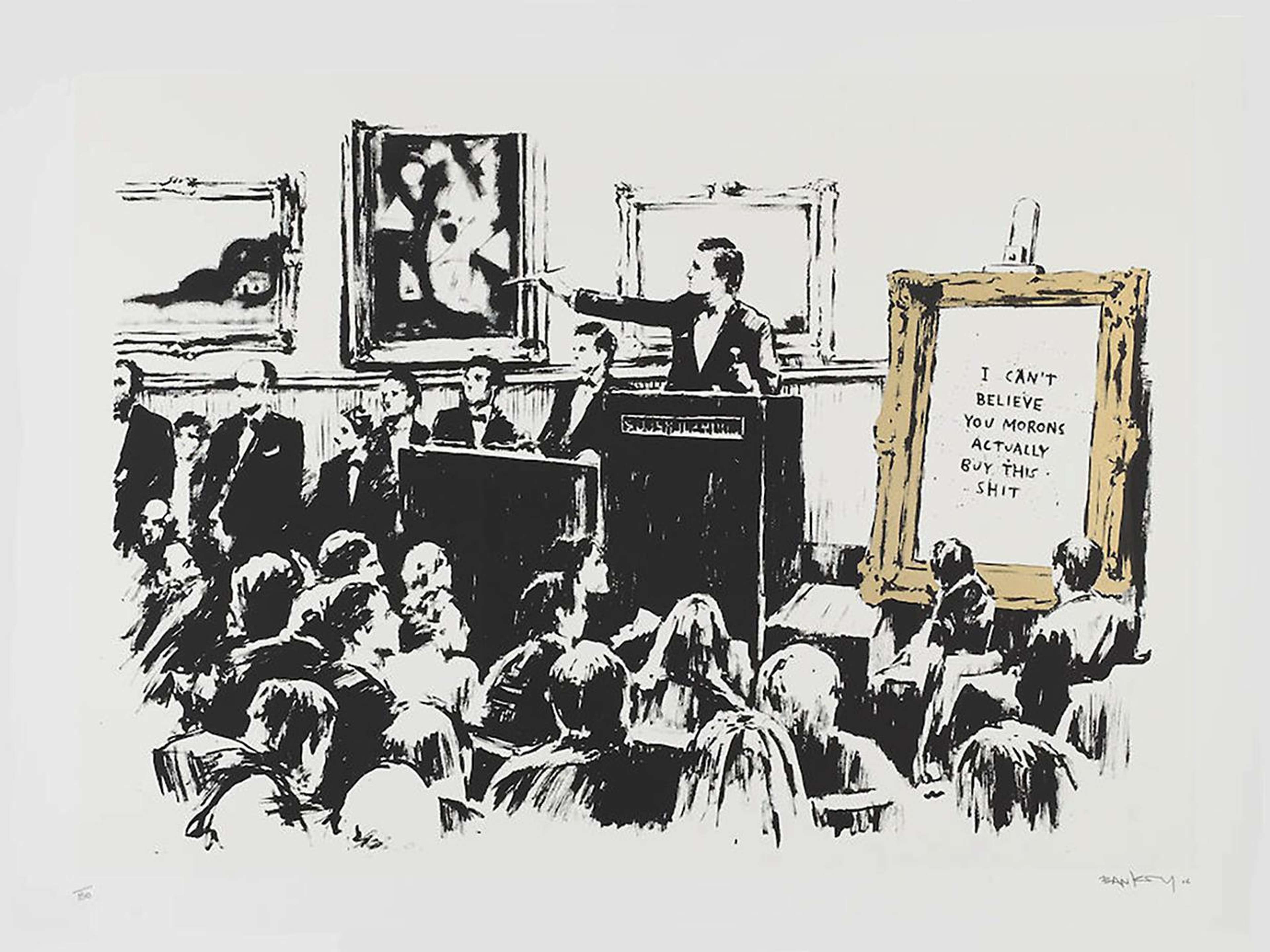

Morons © Banksy 2007

Morons © Banksy 2007By foregrounding Basquiat’s crown, Banksy asserts street art’s place within art history, tracing SAMO’s origins from Lower East Side doorways to museum walls and auction catalogues. Banksy leverages this history to question who gatekeeps “high” art and who benefits when institutions sanctify once-marginal practices.

Banksy previously honoured Basquiat with 2017 Barbican murals

Tortoise Helmet © Banksy 2009

Tortoise Helmet © Banksy 2009In 2017, Banksy painted two murals outside London’s Barbican to coincide with a Basquiat retrospective, posing the same questions that Banksquiat would amplify two years later. By painting on the Barbican’s doorstep, Banksy staged a live critique of institutional framing, the murals serving to criticise establishments that once dismissed street art yet now celebrates and commodifies it.

Basquiat’s crown symbol embodies power, ambition and Black empowerment

Rude Copper (Anarchy) © Banksy 2002

Rude Copper (Anarchy) © Banksy 2002Basquiat’s crown has been interpreted in many ways; some say it pays homage to Andy Warhol, others say it claims artistic authority and signals Black pride. In Banksquiat, the repeated crowns form the Ferris wheel’s cars, a reminder that Black creativity has long powered culture while often being marginalised or appropriated. Banksy’s wheel asks whether today’s recognition truly celebrates Black power, or merely keeps the icons circulating while the system pockets the proceeds.

Banksquiat showcases how Banksy parallels Pop Art ideas

Soup Can (banana, orange and hot pink) © Banksy 2005

Soup Can (banana, orange and hot pink) © Banksy 2005Banksy often satirises and reworks famous art to generate new parallels, such as his Kate Moss series (after Warhol’s Marilyn collection) or Soup Can (after Campbell’s Soup). Banksquiat works in the same way: Banksy takes Basquiat’s crown and puts it in a new setting so modern audiences can judge it against today’s culture and markets. Like Warhol’s packaging and Haring’s figures, the crown has become a clear sign anyone can read, and it asks whether that recognisable sign has been impacted by commodification or whether it still carries its original critique.