Hawthorn Bush in Front Of A Very Old And Dying Pear Tree © David Hockney 2019

Hawthorn Bush in Front Of A Very Old And Dying Pear Tree © David Hockney 2019

David Hockney

653 works

David Hockney has continually reinvented how we look at the natural world across the late 20th and 21st centuries. From the sun-lit hills of California to the quiet lanes of Yorkshire, his distinctive visual language reframes nature through experiments with colour, perspective, and ever-evolving media. Never bound to a single technique, Hockney has moved between printmaking, Polaroid collages, and later iPad drawings, yet his work remains grounded in a lifelong commitment to observation and memory. The result is an oeuvre that invites us to see landscapes as living, shifting environments, captured through the artist’s eye.

Landscapes as a Lifelong Subject

Across his six-decade career, Hockney has returned to landscapes repeatedly, treating them as a constant source of inspiration and experimentation. Even when best known for portraits or poolside scenes, he continued to depict the world around him, whether that meant the Hollywood Hills or the Yorkshire countryside. Throughout, Hockney transformed familiar settings through striking colours, innovative perspectives, and an embrace of new technologies.

Early on, Hockney made a statement with his Los Angeles paintings such as Nichols Canyon (1980), a bright patchwork of winding roads and hills. The work marked a departure from his earlier figurative pieces and embraced a more expressive, almost abstracted approach to landscape. In Nichols Canyon, intense reds, purples, and greens transform an ordinary city canyon into an energetic composition, capturing Southern California’s distinctive blend of urban and natural terrain. The painting’s aerial perspective and exaggerated curves resist the traditional one-point viewpoint, inviting the eye to wander through the scene. This use of dynamic composition and multiple vanishing points would later become a defining feature of Hockney’s landscape vision.

Hockney has long rejected one-point perspective as a way of depicting space. Influenced by cubism and his own study of human perception, he argues that our gaze is never fixed. “The eye is always moving,” Hockney says, and the single static vanishing point inherited from Renaissance painting felt too limited to capture how one actually experiences a landscape. “A view from a stationary point is not the way you usually see landscape; you are always moving through it,” he observes, adding that once a fixed vanishing point is imposed, “you’ve stopped.” Instead, Hockney pursued a way of seeing that could convey the liveliness of vision, injecting multiple perspectives into a single frame to suggest movement and the passage of time.

This philosophy can be seen in his photocollages such as Merced River, Yosemite Valley (1983), composed of dozens of photographs assembled into a single image. The result is deliberately fragmented yet forms a unified whole, resisting the “monocular” authority of the camera’s single view and offering a richer sense of place as it is experienced in real life. Through such experiments, Hockney expanded the possibilities of landscape art, showing that depicting nature is less about reproducing a fixed scene than about capturing the act of seeing itself.

Hockney has often said that drawing teaches you to see more clearly. His textures of grass, the way light plays on water, and the particular shape of trees are rooted in close, direct observation of nature, even when rendered in wildly Fauvist colours or simplified forms. By insisting on looking harder at the world, Hockney carries forward a lesson shared by the great tradition of landscape painting: that art can reveal deeper truths about what we see every day.

The Yorkshire Years: Trees, Roads and The Arrival of Spring

In the 2000s, Hockney made a celebrated return to his roots in the Yorkshire Wolds of northern England. After decades in sunny California, he turned back to the quieter charms of the countryside around Bridlington, the area where he grew up. This homecoming sparked an extraordinary burst of creativity: Hockney painted local trees, roads, and forests with the same intensity he had once brought to his Los Angeles swimming pools. Often working en plein air, he committed himself to recording the changing seasons and shifting atmosphere of Yorkshire’s landscape as they unfolded. The result was a monumental body of work that reimagined British landscape painting for a new era. One of the defining motifs of these Yorkshire years is the country road winding through the landscape. By rendering these familiar routes with a bright palette not usually associated with England’s “pale winter sun,” Hockney offered viewers a renewed appreciation of the region’s beauty. Like the Impressionists before him, he wasn’t painting literal local colour so much as the emotion and sensation of a place.

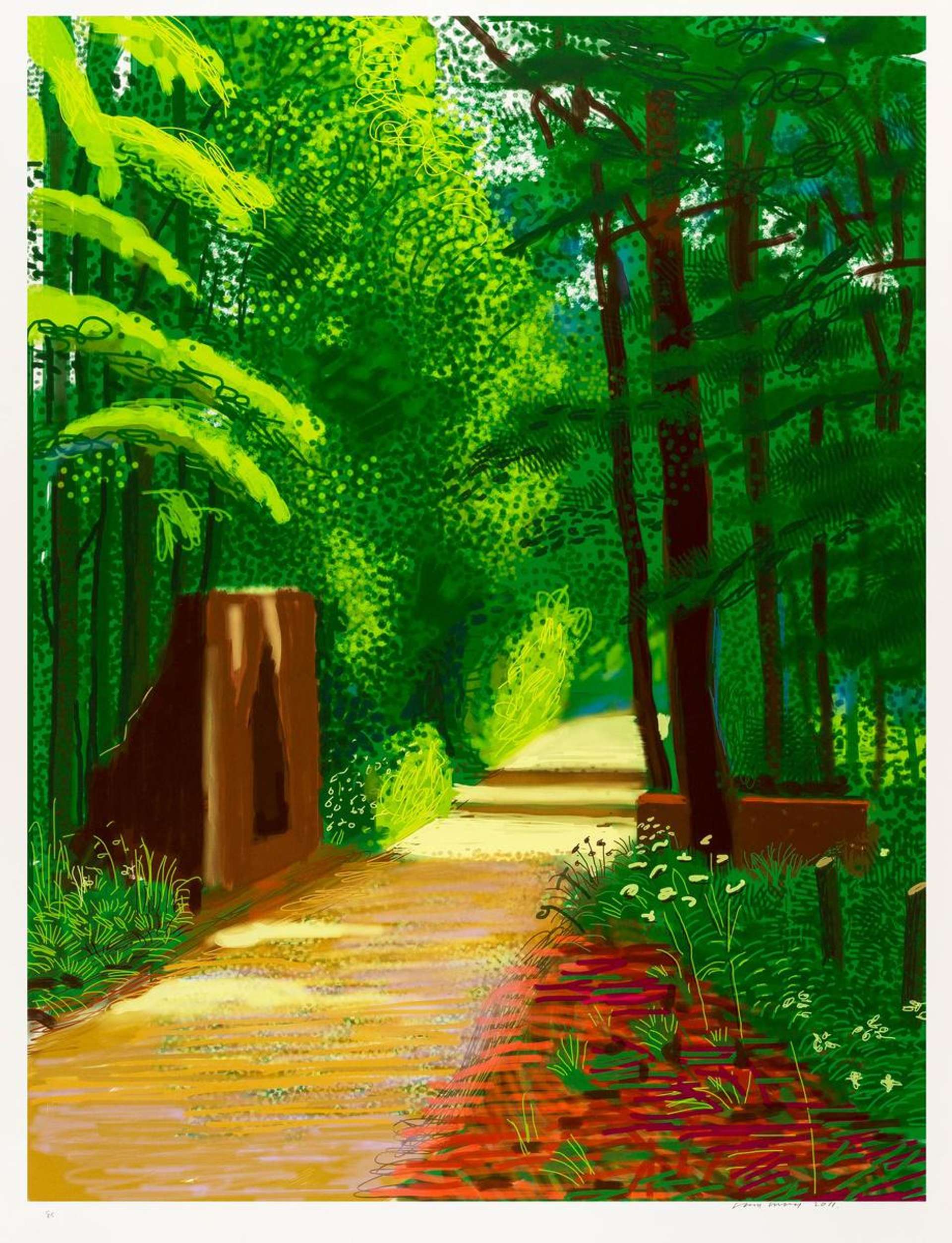

A defining project of Hockney’s Yorkshire years is his series The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire, drawn entirely on an iPad. In 2011, Hockney documented the gradual unfolding of springtime in the Wolds, using the iPad as his canvas. Over the course of January to May, he created a plethora of digital drawings of countryside subjects, capturing everything from the bleakness of late winter to the rich greens of May. Each drawing was dated and later printed in large-scale format, becoming a set of limited-edition works that together chronicle the season’s progression day by day. In October 2025, Sotheby’s staged its first dedicated live auction of Hockney’s The Arrival of Spring prints, offering 17 works from a single owner. Every lot sold, largely exceeding its high estimate, and the sale achieved a £6.2 million result, with six pieces making their auction debut and several setting new individual records for the series.

California, Pools and Light

Hockney’s Yorkshire landscapes really stand in contrast to the bright landscapes of California that initially caught the art world’s attention. After moving to Los Angeles in the 1960s, Hockney became entranced by the city’s suburban settings: sunlit swimming pools, palm trees, and modernist glass-and-stucco architecture. These motifs appeared in some of his most iconic paintings, such as A Bigger Splash (1967), and have their own legacy in Hockney’s printmaking. While the Yorkshire works document gentle English seasonal change, Hockney’s California images glamorise light, leisure, and the ease of modern living. By placing the two side by side, viewers can appreciate how Hockney approaches landscape under very different conditions, yet always with a focus on vision and perception.

Hockney’s Digital Turn: iPads, Brushes and Painting in the Dark

Always looking for ways to innovate, Hockney in his later years embraced digital tools to further transform landscape art. His claim, “I love new mediums,” has been proven time and again through his adoption of technologies like the fax machine, colour photocopier and the Apple iPhone and iPad. This digital turn, which began around 2009, opened up new possibilities for drawing from life. It also ensured that Hockney’s influence on how we see landscapes continued well into the 21st century, resonating with a generation raised on screens and instant imagery.

Hockney’s foray into digital painting started in 2008 when he began drawing on an iPhone using an app called Brushes. By 2010, with the release of the iPad, he had a larger canvas and quickly realised the potential of the device for serious art. With the iPad and the Brushes app, Hockney could access every colour imaginable, work rapidly without waiting for paint to dry, and even paint in the dark thanks to the device’s backlit screen. The speed and flexibility of the medium suited his longstanding desire to work directly from observation without delay.

Hockney showed that serious art could be made on a touchscreen, and in doing so he helped legitimise digital painting in the fine art world. When he first exhibited his iPad drawings in 2011, critics and viewers were astonished at how painterly and rich they were. Despite being created with pixels, they carried Hockney’s unmistakable style. One reason is that Hockney approached the iPad much like his physical media – he even said there’s no difference in looking: “If you have drawn all day [on an iPad], there is no cleaning up needed,” he said, but the act of drawing and observing is the same. By fusing traditional artistic principles with cutting-edge tech, Hockney once again changed how we view landscapes.

By the mid-2010s, Hockney even moved on to multi-screen video installations (depicting, for instance, a drive down a tree-lined road filmed by multiple cameras – another experiment in capturing landscape from many angles). But it is his iPad landscapes that remain most influential, as they directly bridge the gap between the classic and contemporary. They proved that even in his seventies and eighties, Hockney could lead a revolution in the way we see.

Landscapes in Print

One of the most distinctive ways Hockney reshaped landscape art is through printmaking. Prints gave him a space to test ideas about colour, repetition, and perception with a freedom that painting did not always allow. Across his career, he returned to serial formats to see how a landscape shifts when viewed again and again under different conditions.

A key early example is The Weather Series (1973), a suite of lithographs depicting rain, snow, mist, wind, sun, lightning – each shown through a simplified landscape. Inspired in part by Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints, Hockney uses the flat planes of lithography to strip away detail and draw attention to the sensation of how weather feels, rather than how it looks. As a series, the prints form a narrative of nature in flux, where weather alters mood, visibility, and emotional tone from one image to the next. This use of seriality is central to Hockney’s approach, as he encourages a more active form of looking, one that mirrors how we actually experience the world over time.

This focus on time carries through much of Hockney’s later landscape print work. Series such as The Arrival of Spring extend his exploration of change and perspective across days and seasons. The idea has clear roots in Impressionism, but Hockney’s version feels distinctly contemporary, shaped by new processes and digital tools. The result is a heightened awareness of landscape as something lived and observed.