The Dog, The Baby And The Globe

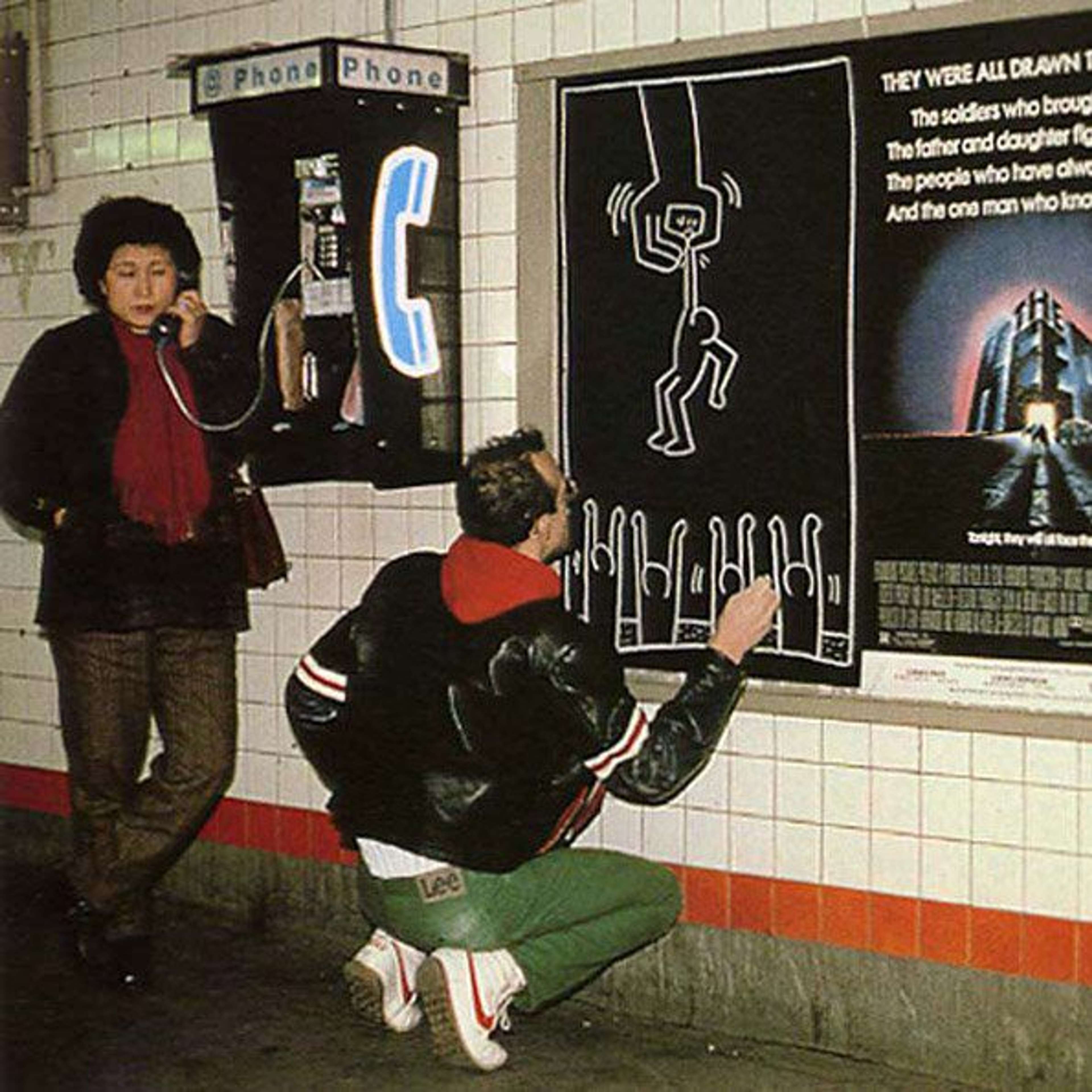

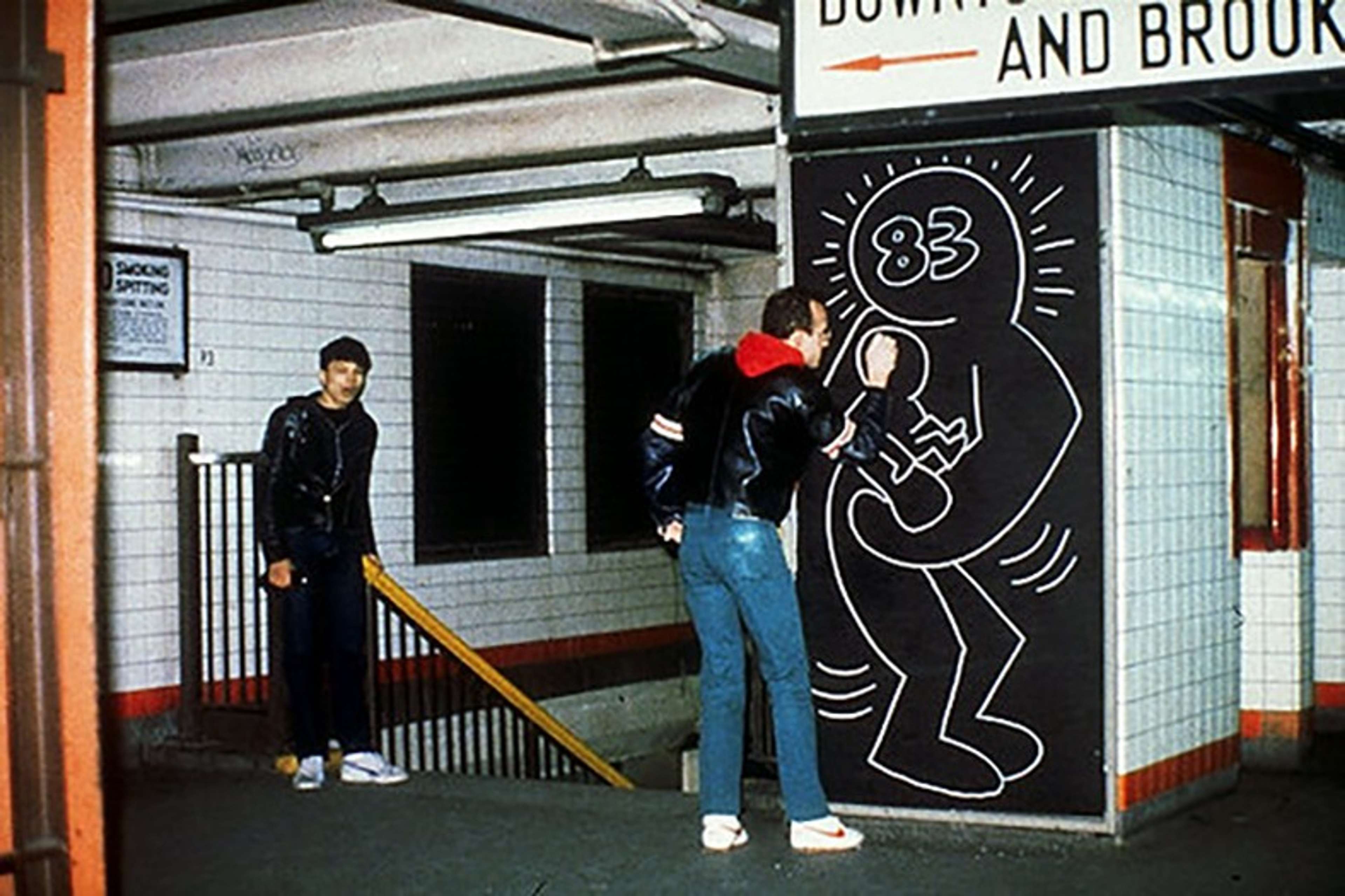

“Keith in the subway” (CC BY-NC 2.0) Ken Lig / JUST SHOOT IT! Photography

“Keith in the subway” (CC BY-NC 2.0) Ken Lig / JUST SHOOT IT! Photography

Interested in buying or selling

Keith Haring?

Keith Haring

249 works

Influenced by his study of Semiotics at the New School, Keith Haring filled his work with signs and symbols in order to create a pictorial language that was both deeply personal and easily accessible to the general public who first encountered his drawings on the New York subway.

In this way, his work became a truly ‘public’ art form, existing outside of what Haring saw as the elitist market of contemporary art. Icons such as his Radiant Baby and Barking Dog exuded joy and positivity to passers-by long before the critics knew what had hit them.

Here we take a closer look at some of the most familiar images from Haring’s work, what they symbolise, what inspired them, and how Haring created them.

For a closer look at how street art shook up art history, and changed the art market, read our How Street Art Has Changed The Art Market.

What inspired Keith Haring?

Haring developed a strong interest in drawing as a child, learning basic cartooning skills from his father and inspired by popular culture animations like Walt Disney, Dr. Seuss and Looney Toons. The artist’s playful and brightly coloured style plays into the visual language of these iconic cartoons in an entirely unique way and it is clear why Haring’s work is still so popular today.

After moving to New York in 1978, Haring became immersed in and heavily influenced by the emerging street art and hip-hop scene, which often took the form of graffiti and murals across Harlem and the subway. Jean-Michel Basquiat and Kenny Scharf, key figures in this alternative art scene, became close with Haring and the three artists developed a shared interest in making work outside of traditional art spaces. Haring used his distinct graffiti-inspired style to create a truly public art, just as Basquiat had done before him, that merges high art with popular culture. Crucially however, Haring never considered himself to be a graffiti artist, his Subway Drawings differing in location, timing and medium from his contemporaries.

“Keith in the subway” (CC BY-NC 2.0) Ken Lig (JUST SHOOT IT! Photography)

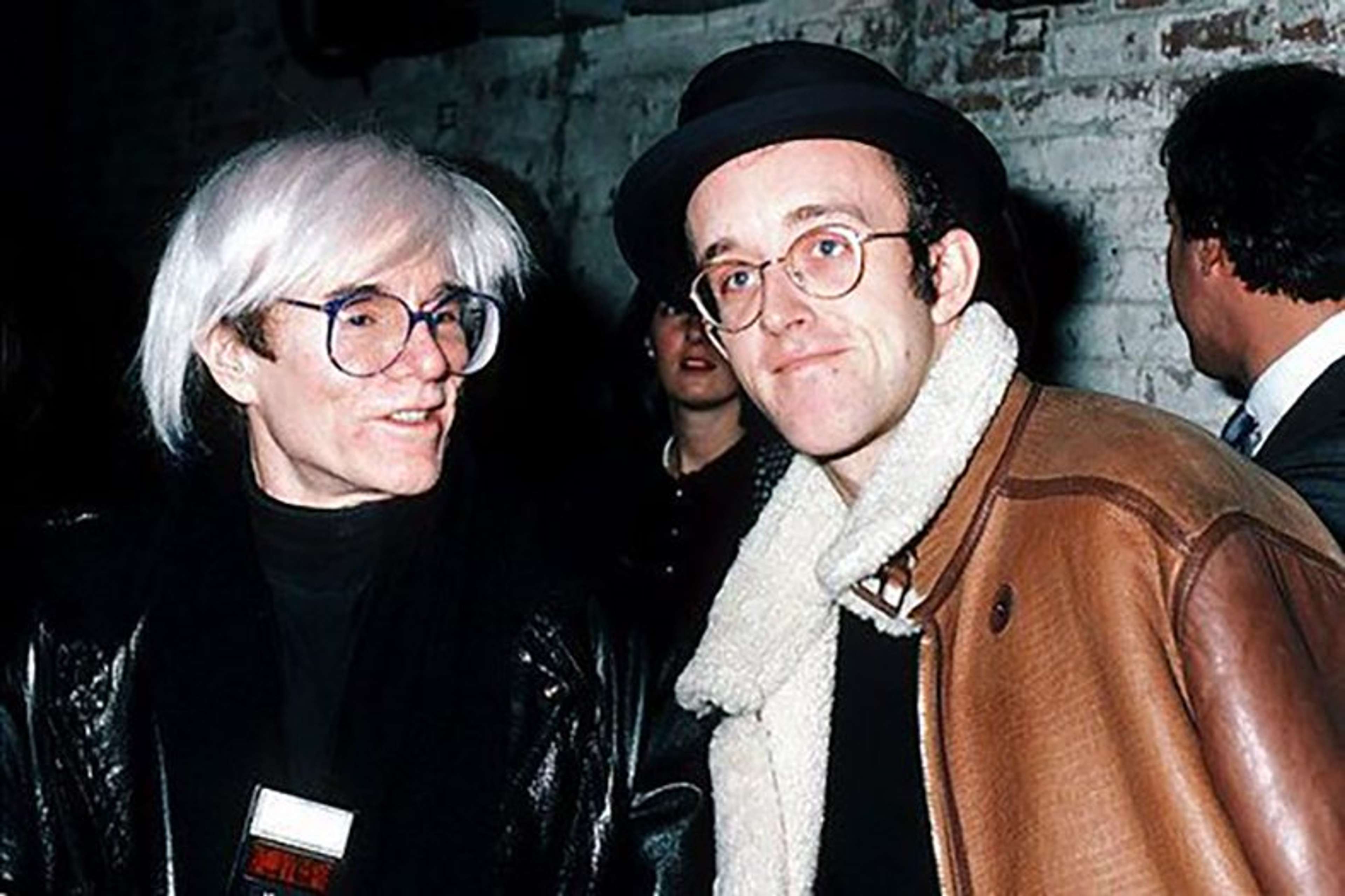

“Keith in the subway” (CC BY-NC 2.0) Ken Lig (JUST SHOOT IT! Photography)As an artist who grew up in the 1960s and ’70s, Haring was undoubtedly inspired by the Pop Art movement in his use of saturated block colours like blue, red and yellow, flat, simplified shapes and dark, bold lines. Haring’s work sought to bridge the gap between high art and popular culture, a key component of the Pop Art movement, by using the visual language of mass consumer objects. Notably, as Haring shot to stardom, he was befriended by the leader of the Pop Art movement, Andy Warhol, who became his mentor. From Warhol, Haring learned about the importance of repeating images and expanding his artwork through unprecedented channels in the commercial world. It is important to note that Haring’s intuitive working process that prioritised the hand of the artist, through his use of organic shapes and motifs, marks him as distinct from his predecessors.

“Andy Warhol and Keith Haring” (CC BY-NC 2.0) Ken Lig (JUST SHOOT IT! Photography)

“Andy Warhol and Keith Haring” (CC BY-NC 2.0) Ken Lig (JUST SHOOT IT! Photography)What is the meaning of the Barking Dog?

The Barking Dog has become one of Haring’s most iconic symbols, first appearing in his New York subway drawing series from 1980–85. It emerged as a symbol of oppression and aggression, acting as a warning to the viewer of the abuses of power that pervade everyday life in America and beyond. Traditionally used by artists to represent loyalty, companionship and obedience, Haring subverts the symbol of the dog to remind viewers to think critically about those who shout the loudest. Similarly, street artist Banksy can be said to have picked up Haring’s mantle, appropriating symbols such as the barking dog to spread a new message of distrust in figures of authority.

What is the meaning of the Radiant Baby?

Rooted in Haring’s encounter with the Jesus Movement of the 1970s, motifs such as the Radiant Baby, Angel and Flying Devil, demonstrate how the artist appropriated and subverted religious iconography to reflect contemporary concerns of his generation. Many have read this subversion as an overt critique on organised Christianity, and particularly the church’s position on the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s, to which Haring tragically succumbed.

Here the baby represents the ultimate symbol of innocence, radiating positive energy from its crawling pose, in what Haring called, “the purest and most positive experience of human existence.” As his career progressed, however, the baby motif found itself in ever darker scenes, covered in the Kaposi’s sarcoma associated with advanced HIV infection, or at the centre of a mushroom cloud or UFO abduction. In this way the baby is often associated with Haring himself, a figure whose innocence and purity led him to revolutionise the art world for a brief moment before his untimely death.

What is the meaning of the Heart?

Similarly to the radiant baby, Haring’s Heart motif, often seen being held aloft by a crowd of dancing figures, is a symbol of optimism and love. While it can sometimes represent romantic love – as when it is held between an androgynous couple – it is also read as a wider symbol of collectivity, community and compassion, as when it is held by two hands or when it also encompasses a globe within it. Here again a religious meaning can be inferred, as the sacred heart is pervasive across Christian art, however the heart is also a staple of cartoon imagery in which Haring was well versed from a young age. And while his later work often took a more erotic or tragic turn, the innocence of the love heart, usually painted in a bright primary red, remained present all the way through.

What is the meaning of the Dancing Figure?

The dancing figure or stick figure is perhaps one of Haring’s most well known motifs, appearing on t-shirts and billboards across the world still today, and can be seen to represent the joy and energy of the New York club scene – and in particular the gay scene – in the ’70s and ’80s. With bold energy lines radiating from their bodies the figures effortlessly evoke freedom and ecstasy, whether engaged in the act of breakdancing or holding their hands high above their head as if moving to the beat of an unseen DJ.

Occasionally the figures become conjoined or stacked evoking a further sense of community and solidarity, their energy lines turned into the squiggles and symbols usually associated with Aztec or Aboriginal art. Commenting on this particular motif, Haring has said “My drawings don’t try to imitate life; they try to create life, to invent life.”

What is the meaning of the Globe?

Often depicted above a crowd of dancing figures or inside a cartoon heart, the globe is immediately recognisable as an icon of peace and collectivity. As with many of Haring’s other motifs it is usually surrounded by radiant energy lines or supported by a pair of hands, suggesting the artist’s belief in the importance of collaboration and positivity in the face of the prejudice and division brought about by politics and the global AIDS crisis which had a huge impact on New York counterculture.

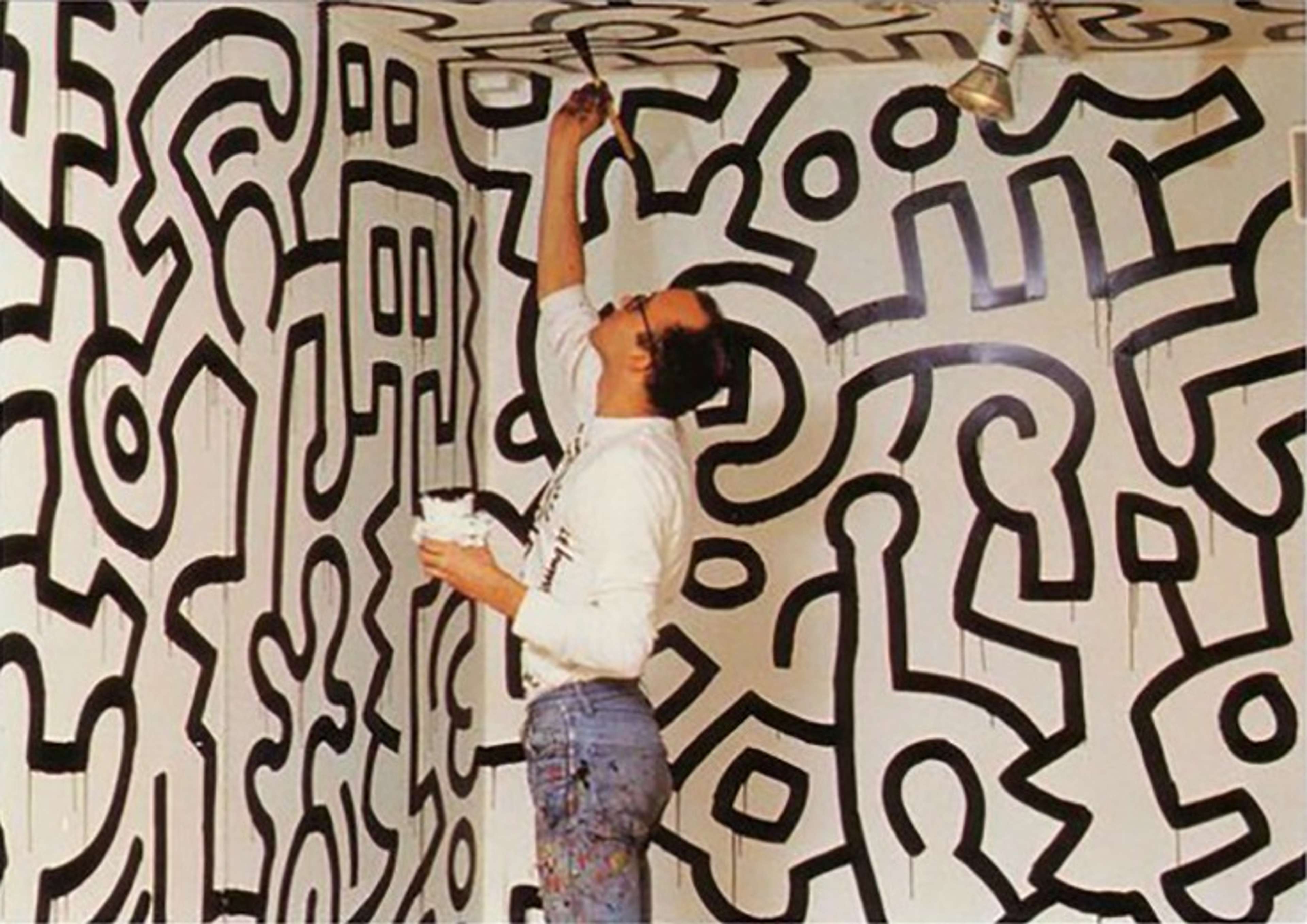

“Haring at work” (CC BY-NC 2.0) Ken Lig (JUST SHOOT IT! Photography)

“Haring at work” (CC BY-NC 2.0) Ken Lig (JUST SHOOT IT! Photography)What materials did Keith Haring use in his work?

Across his short but prolific career, Haring worked across a variety of different mediums, creating more than 3,000 works on paper and around 300 paintings, as well as sculptures and murals.

Some of Haring’s most iconic motifs emerged from his Subway Drawings from 1980-85, of which he produced around 5,000, that were created with white chalk on blacked out advertisement panels. Through obsessive repetition of subject across the drawings, Haring produced a memorable pictorial language, a syntax of signs, that was quick and simple to execute to avoid being arrested. Unlike the graffiti artists who he is often closely associated with, Haring used white chalk and worked during the day so that he could interact with his audience. Whilst his contemporaries used spray paint or markers, Haring’s use of chalk meant that his work could be removed more easily and had an ephemeral and performative quality to it. Haring’s friend from the School of Visual Arts, Tseng Kwong Chi, would follow him around the subways and photograph his chalk drawings before they were covered or stolen.

Haring experimented with a number of printmaking techniques in his career such as lithography, screen printing, etching, woodcuts and embossing. These printing mediums worked to bridge the gap between his unique pieces and the reproduction of his imagery to promote the accessibility of his popular imagery. His experiments with silkscreen likely stem from an admiration of Andy Warhol. Tellingly, in Haring's Andy Mouse series, his tribute to Warhol, Haring takes a leaf out of his elder's book and tries his hand at Warhol's silksceen process.

Finally, Haring also worked in painting and sculpture, creating life-sized figures in 3D and billboard-sized murals that occupied public spaces and communicated strong messages to the community.

Does Keith Haring’s art have a symbolic language?

Haring was strongly aware of how pictures could function just like words. “I was always totally amazed that the people I would meet while I was doing them were really, really concerned with what they meant. The first thing anyone asked me, no matter how old, no matter who they were, was what does it mean?” he said.

Inspired by Egyptian hieroglyphics, Haring adopted a system of expression that reduced complex and weighty concepts into a simple and brightly coloured symbol. Evolving the abstract shapes of his early drawings, each recurring motif holds its own set of meanings that have come to form a universal language to be seen and understood by the masses of New York.

In the radiant baby, the barking dog, the globe and other symbols, we can see Haring’s fascination with hieroglyphs, pictograms and other universal languages – something that still resonates with art lovers today, who are used to communicating with images and emojis as well as words.

Interested in collecting Keith Haring prints? Check out our Keith Haring Market Watch to learn the top 10 most investable prints for 2023.

2025 Exhibitions

To My Friends at Horn: Keith Haring and Iowa City

Open in Iowa City at the Stanley Museum of Art until March 9, 2025, this exhibition celebrates Haring's artistic legacy and the connections he forged during his visits to Iowa City in the 1980s. At its heart is A Book Full of Fun (1989), the mural Haring painted for Ernest Horn Elementary School, currently on loan to the Stanley Museum of Art while the school undergoes renovations. The exhibition also features a selection of artworks, photographs, and archival materials that provide insight into Haring’s impact and creative process.