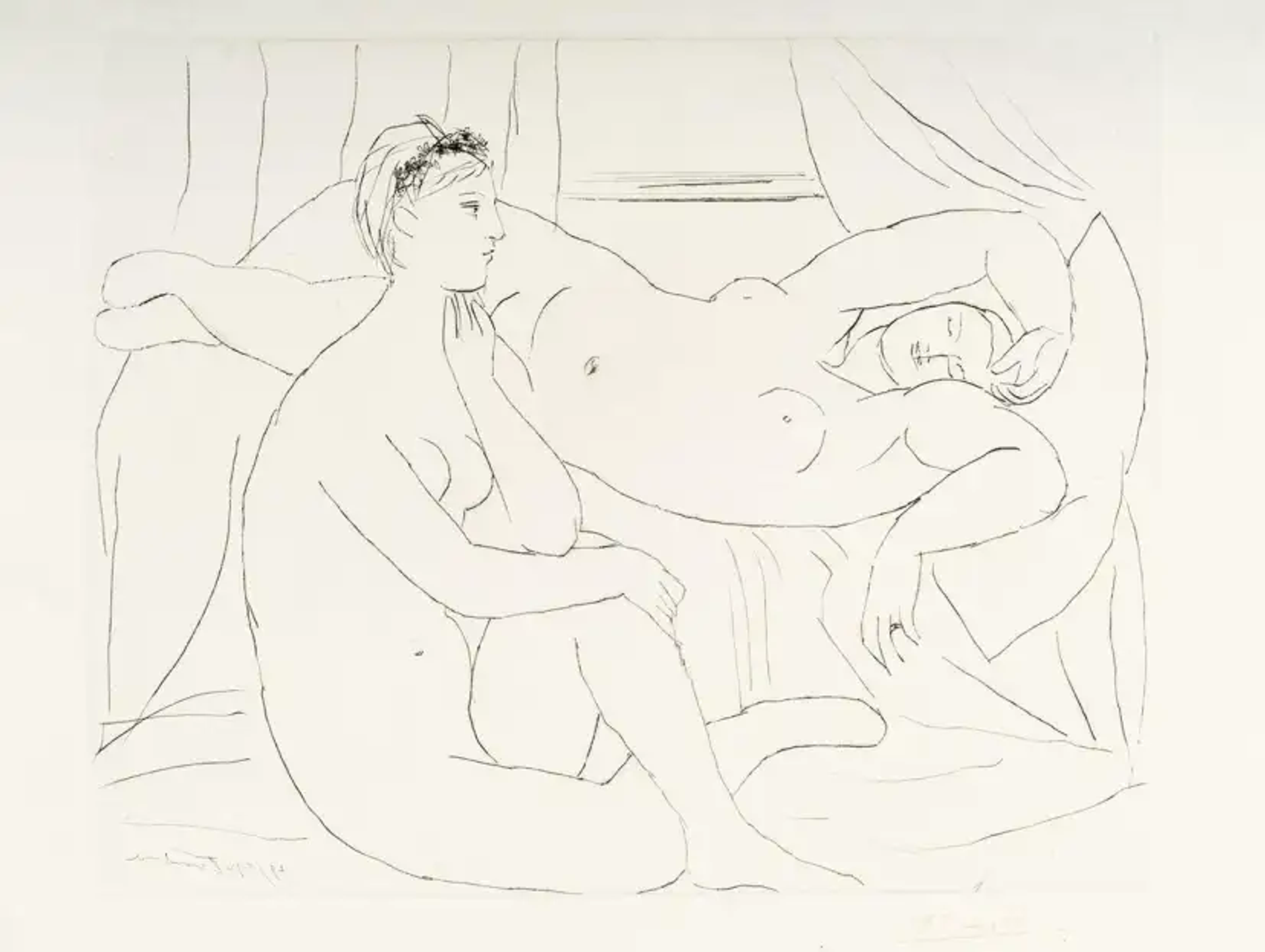

Minotaure Une Coupe La Main Et Jeune Femme (signed) © Pablo Picasso 1933

Minotaure Une Coupe La Main Et Jeune Femme (signed) © Pablo Picasso 1933

Pablo Picasso

160 works

While Pablo Picasso is often celebrated for his revolutionary Cubist works, a lesser-explored yet equally fascinating chapter of his artistic journey is his Neoclassical phase. Beginning in the early 1920s, Picasso – already a master of innovation – made a seemingly counterintuitive pivot: he turned back to the classicism that many of his avant-garde contemporaries had rejected. This period, marked by a return to traditional themes, techniques and forms, reveals a different facet of Picasso's inexhaustible creativity and ability to go against the grain.

The Neoclassical phase of Picasso is a testament to his versatility and deep understanding of art history. During this time, his work displayed a renewed interest in the human form, classical themes and clear, structured compositions, drawing inspiration from the Renaissance and ancient Greco-Roman art. This period, often overshadowed by his earlier and more radical Cubist works, offers a unique window into Picasso's psyche, showcasing his ability to both disrupt and embrace artistic norms.

The Historical Context of Picasso's Neoclassical Phase

The end of World War I in 1918 marked a turning point in global history, which had a significant impact on the trajectory of modern art. The catastrophic impact of the war, which had ravaged much of Europe, left a deep scar on the collective psyche of the continent. In the wake of such devastation, there was a palpable shift in societal values and cultural expressions. This period saw a widespread retreat from the avant-garde fervour that had defined the early 20th century, giving way to a yearning for order, stability and a return to more traditional values. This change in sentiment was perhaps a coping mechanism, a way for society to find solace in the familiar and the enduring amidst the ruins of war.

In the art world, this shift manifested as a departure from the radical innovations and rebellious spirit that had characterised movements like Cubism, Futurism and Expressionism. Artists, many of whom had witnessed the horrors of war first-hand, began to question the pre-war optimism about progress and modernity. There was a growing disillusionment with the idea that modern technology and new ways of thinking could lead to a better world. Instead, artists started to look backwards, finding comfort in the timeless beauty and structured forms of classical art. Picasso, who had been a pioneering figure in the development of Cubism before the war, was not immune to this change in cultural climate.

The Dawn of Picasso's Neoclassical Period

In February 1917, Picasso undertook his first trip to Italy, in order to design the curtain and costumes for the ballet Parade. The journey would impact him deeply and as the artist spent time in Rome, Naples and Florence, he immersed himself in artworks from Classical Antiquity and the Renaissance. Picasso’s Neoclassical phase can be seen as a response to the broader societal need for a return to order and tradition, as well as a personal reaction to these new experiences. This period in the artist’s career was marked by a stark contrast to his earlier works – where once there were abstract forms and fragmented perspectives, now there were clear, harmonious compositions and a renewed focus on the human figure. This return to classicism was not just a nostalgic revival of past styles; it was a recontextualisation of traditional art forms in the light of contemporary experiences.

Picasso was not the only artist to embrace Neoclassicism during this time, although his stature and influence brought significant attention to the revitalisation of the movement. His adoption of the style was seen as a legitimisation of the return to traditional forms and helped to propel the trend forward. His Neoclassical works offered a counter-narrative to the prevailing trends of abstraction and conceptualism, and played a crucial role in the broader artistic discourse of the early 20th century.

Analysing Picasso's Neoclassical Style: Techniques and Reception

In Picasso's Neoclassical phase, he embraced the clarity, order and balanced proportions characteristic of classical art. His paintings from this period often feature well-defined, sculptural figures, reminiscent of ancient Greek and Roman statues. The lines are cleaner and more precise, and the compositions are typically more harmonious and less chaotic than his Cubist works. One of the most notable aspects of Picasso's Neoclassical style is his renewed focus on the human form: his figures during this period are robust and rounded, exuding a sense of calm and stability. This is particularly evident in his depictions of women, which often convey an air of serene dignity and grace. The influence of Renaissance artists like Raphael and Michelangelo is palpable in the anatomical accuracy and the idealised forms of these figures. In terms of colour, Picasso's Neoclassical paintings are often more subdued than his earlier works, favouring a more restrained palette that underscores the sense of classical elegance. He also experimented with various textures and techniques to achieve a more sculptural quality in his figures, emphasising volume and depth in a way that was reminiscent of classical sculpture.

The reception of Picasso's Neoclassical work was mixed at the time. Some critics and fellow artists viewed this shift as a retrogressive move, particularly in light of the groundbreaking nature of his Cubist work. There was a sense among some that Picasso was abandoning the avant-garde principles he had once championed. However, others appreciated the technical mastery and beauty of these works, recognising the depth of Picasso's engagement with the artistic traditions of the past. It demonstrated that the exploration of classical themes and techniques could be a forward-looking endeavour, rather than a simple retreat into the past. Picasso's Neoclassical works challenged the boundaries between the traditional and the modern, showing that the two could coexist and even enrich one another.

Exploring Themes and Subjects in Picasso's Neoclassical Works

During this phase, Picasso's subjects often harkened back to classical mythology and the human form, reflecting a significant shift from the abstract, fragmented subjects of his earlier works. A recurring theme is his fascination with the character of the Minotaur and bacchanalia. The Minotaur, a mythical creature with the body of a man and the head of a bull, became a significant motif in Picasso's art from the 1920s all the way into the 1950s, appearing in approximately 70 of his works. The Minotaur's duality – human and beast – allowed him to explore themes of savagery and civilisation, desire and repulsion, violence and tenderness. Picasso identified with the Minotaur, seeing parallels between its traits and his own – from the bullfighting culture of his Spanish heritage to his personal attributes of virility and masculinity. This connection is notably illustrated in works where the Minotaur engages with female figures – a troubling reminder of Picasso’s own distressing relationships with women.

His portrayal of the Minotaur varied from menacing to vulnerable, reflecting his own personal struggles and the turbulent socio-political climate of the time; the character also appears in Guernica as a symbol of rebellion and strength. The figure is often depicted in scenes of bacchanalia, wild and mystic festivities dedicated to the god Bacchus, where it symbolised primal instincts and a connection to the darker aspects of human nature.

The theme of bacchanalia is also recurrent in Picasso's work, often reflecting the societal excesses and the hedonistic pursuits of the interwar period. These scenes are filled with a sense of unrestrained energy and chaotic movement, capturing the spirit of the bacchanalian revelries. Through these depictions, Picasso engaged with themes of ecstasy, excess and the human propensity for indulgence and debauchery. His obsession with the Minotaur and bacchanalia allowed him to explore a range of complex themes, from personal identity and inner conflict to broader societal issues.

Neoclassicism Through the Lens of Pablo Picasso

For Picasso and his contemporaries, the Neoclassical movement was a way to reconcile the lessons of the past with the realities of the present. It was an attempt to restore a sense of humanity and beauty in a world that had seen too much destruction, and this period is a poignant reminder of the power of art to reflect and shape the collective consciousness of a society in times of profound change.

The Neoclassical phase of Picasso's career, while relatively brief compared to his other periods, had a lasting impact on the development of modern art. It demonstrated the artist's remarkable ability to adapt and evolve, challenging the conventional narrative of artistic progress and evolution. Picasso's engagement with classical themes and techniques during this phase enriched his own artistic vocabulary while also offering a bridge between the past and the future, influencing subsequent generations of artists. This period of Picasso's work remains a testament to his enduring fascination with the human form and his relentless pursuit of artistic reinvention.