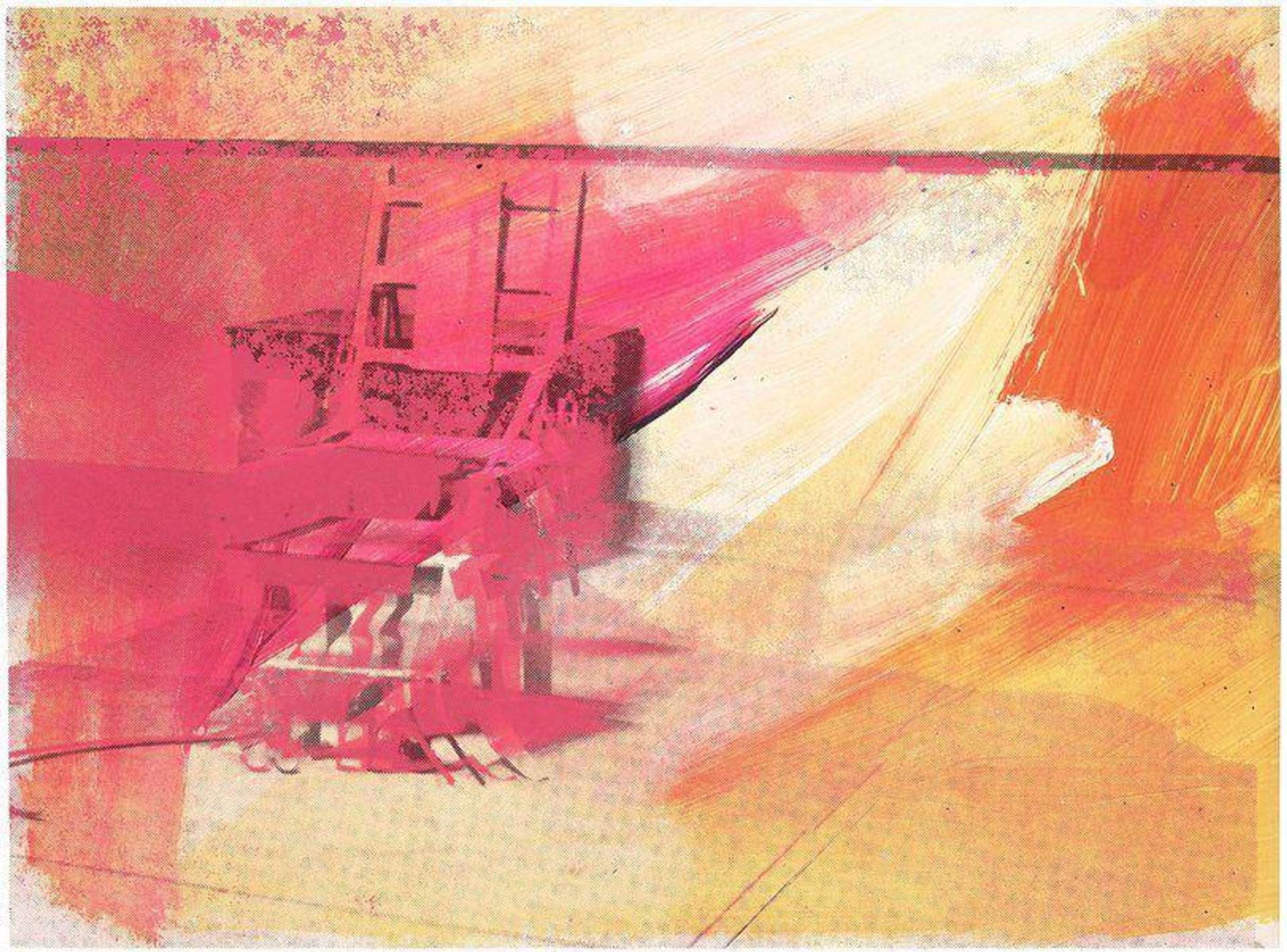

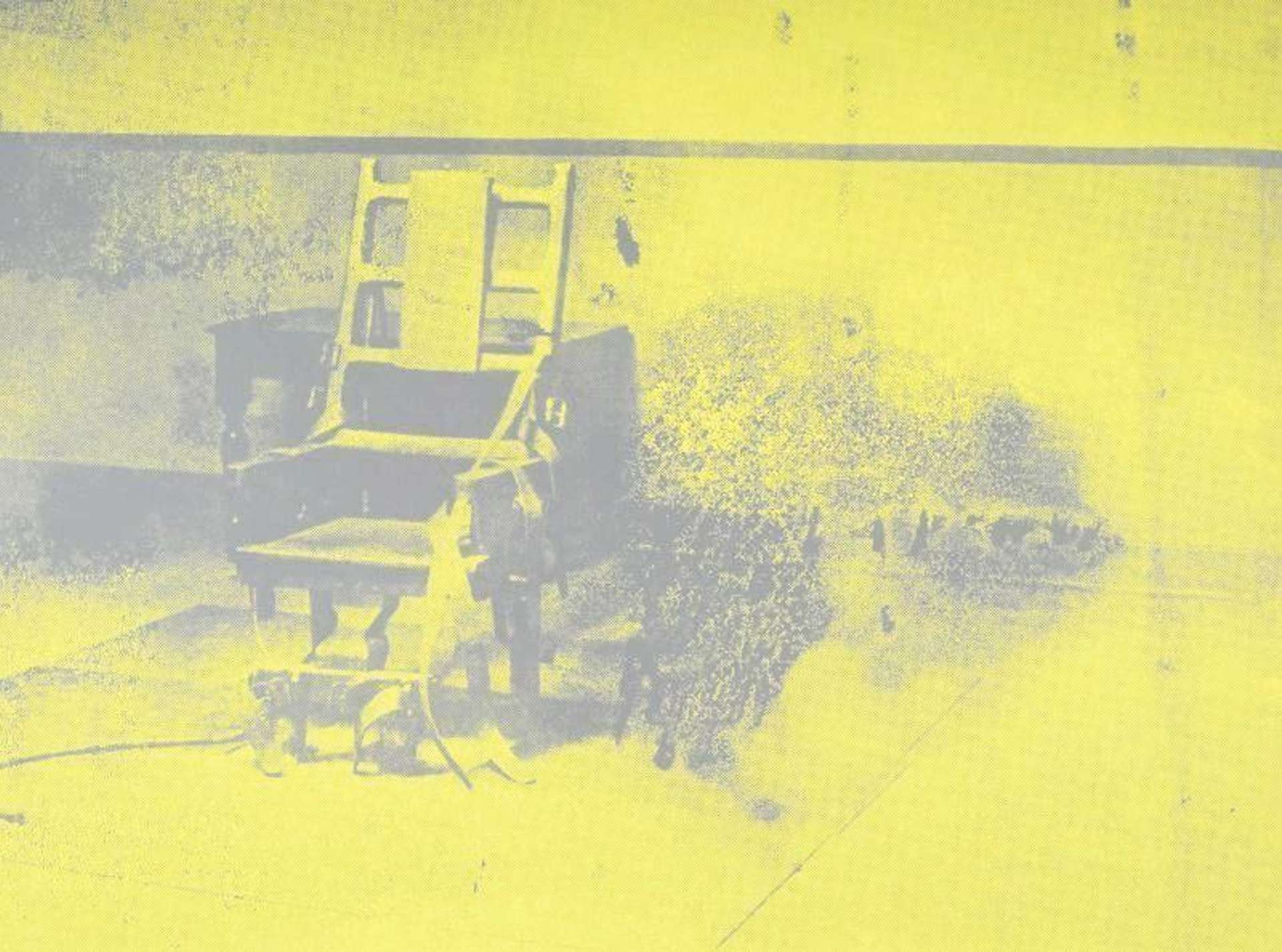

Electric Chair (F. & S. II.82) © Andy Warhol, 1971

Electric Chair (F. & S. II.82) © Andy Warhol, 1971Live TradingFloor

Read the final chapter of Richard Polsky’s mini series on the world of Andy Warhol authentication.

CHAPTER 8

The failure of Alice Cooper’s painting to sell raised some interesting questions about the Warhol market. Specifically, there was great difficulty in getting the auction houses to accept paintings that weren’t authenticated by the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board. In 2016, Christie’s hosted a single owner sale, called “Andy Warhol Works from a Private Collection.” The catalogue’s cover featured an unfinished classic red and white Campbell’s Soup Can painting. Yet, upon opening the sales catalogue, the name of the owner of the collection was nowhere to be found. I remember calling Christie’s Contemporary Art Department to learn more about the sale. The specialist I spoke with refused to divulge the name of the seller — which seemed strange for a somewhat high-profile sale.

All I was told was that the owner was someone “as close to Andy as you can get.” Was the seller one of Andy’s two brothers? A bodyguard? A former key employee? The sale itself contained approximately twenty pictures — most from the 1960s. There was no doubt they were all genuine. But a fair number of them looked unfinished, or in some cases felt like rejects. They all came with estimates well below what would have been the normal estimates for similar works. Ultimately, every painting sold, in most cases below estimate, to (who else?) but the Mugrabi family.

The take away from the sale was that Christie’s accepted a group of Warhol paintings that did not appear in the Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné — which almost never happened. I assume Christie’s had the full support of the Andy Warhol Estate. But in this case, they may have been repaying a favour. There has always been an implied understanding between the auction houses and artist estates to help each other.

The messy politics of art authentication

With the termination of many of the art authentication boards (over ten years ago), the major auction houses began approaching the estates for unofficial opinions about the authenticity of works they were offered. The various estates would cooperate whenever possible. However, their advice came strings attached. Namely, if the estate wanted a painting or a group of works to appear at auction (or conversely not to appear), they expected the auction house to “go with the program.”

These off the record arrangements were well-known by art world insiders. What no one could determine were the politics behind the deal-making. While you couldn’t prove it, the difference between getting a painting approved by an art authentication board — and not — sometimes came down to where you ranked in the art market food chain. One of the great stories that illustrates this point was the Ruth Kligman controversy. Ms. Kligman was well-known as Jackson Pollock’s mistress. Her sudden appearance in Pollock’s life caused all sorts of grief for his long-suffering wife Lee Krasner. Kligman achieved notoriety for being in the car on the fateful night when a drunken Pollock took a curve too quickly and he and Kligman’s girlfriend (Edith Metzger) were thrown from the car and killed. Allegedly, a few weeks before this tragic event, Pollock gave Metzger the last painting he created as a gift. The modest-size work was a red, silver, and black “Drip” painting — worth a small fortune if proven genuine.

Many years later, Ruth Kligman submitted the painting to the Pollock-Krasner Foundation art authentication board. Rumour had it that regardless of what the committee felt about the painting’s validity, there was no way in hell they were going to approve it — given the cruelty Kligman displayed toward Lee Krasner. Assuming this story is true, it presents an interesting case study in the responsibilities and ethics of an art authentication board.

Image © Christie's / Number 19 © Jackson Pollock 1948

Image © Christie's / Number 19 © Jackson Pollock 1948You have to remember that authentication board members are human. They bring to the table any personal issues they may have which are connected to the artist they’re validating. A board member may very well have known the artist during his lifetime and objected to a specific person from his inner circle, including his business manager, one of his dealers, or a collector. While an authentication committee participant is supposed to remain neutral, it’s almost impossible to do so.

I know of several instances where a painting, that to my eye was valid, was rejected by an art authentication board member because he had an axe to grind with the individual who submitted the painting. The problem is that a board’s decision is final — which means there isn’t much you can do about it — short of suing. While a few deep-pocketed (or extremely resourceful) individuals elected to sue an authentication board, these lawsuits always ended badly for both parties. It’s no wonder that by 2012, the art authentication boards for many famous artists were no longer functioning.

With so many paintings by the likes of Warhol, Basquiat, and Haring which lacked authentication certificates being submitted to the major auction houses, it made me wonder what it would take for them to accept outside authentication. The problem, as it currently stands, is that Sotheby’s and Christie’s are basically too successful to accept paintings I’ve authenticated. One of their executives once explained to me: “We know you do good work. But we’re offered a $5 million Warhol every week that’s already in the catalogue raisonné. If we take something you’ve authenticated that’s not in the catalogue, then we have to explain to the potential buyer why it wasn’t included, and the whole thing becomes controversial and time-consuming.” Essentially, he was telling me they have plenty of business; it’s simply not worth it for them.

Taking stock of the market for Warhol

We currently live in a robust art market. Every round of sales seems to set new records for individual artists. In May 2022, Andy Warhol’s Shot Sage Blue Marilyn sold for a staggering $195 million. Perhaps, as the expression goes, a tree really does grow to the sky. But if the world economy ever undergoes a major shift, and prices for art stagnate or even fall, the auction houses may find themselves being a little more flexible. The value of genuine Warhols, which don’t appear in the catalogue raisonné, is considerable. Sotheby’s and Christie’s will probably discover they are leaving more money on the table than they think.

This means there are plenty of opportunities for the next tier of auction house to get involved — which is precisely what happened with Alice’s painting and Larsen Art Auction. Although the red Little Electric Chair failed to find a buyer, Scott Larsen still felt encouraged, and expressed to me they wanted to try again with another Warhol I authenticated.

As for Alice’s painting, it continued to remain in storage. I kept in touch with Shep Gordon, but nothing developed, as far as finding a new venue to sell the painting. While I continued to ponder the issue, the art authentication business was expanding on a steady basis. Besides Warhol, the demand for authenticating purported Basquiats and Harings was particularly active. There was a continuous stream of owners of alleged Basquiats who kept finding paintings in storage lockers. This replaced the old Basquiat standby of saying you acquired it from one of his drug dealers. As for Keith Haring, a growing source of fake Subway Drawings was from someone who claims he got it from a former member of the maintenance department, at the New York Subway System.

What's the future of the art authentication business, then?

Regardless, the future of the art authentication business might lie in assembling an “all-star” team of authentication experts. If you could put together a three person group which consists of an acknowledged authority in connoisseurship, a scientific analysis professional, and an attorney who specialises in the high-end art market, you might be able to at long last convince Sotheby’s and Christie’s to accept outside authentication — in lieu of an artist estate’s original authentication board (which no longer exists).

The idea has a lot of merit. Auction houses live in fear of making a mistake and selling a painting which at a later date is declared a forgery. While refunding a large amount of money might harm the bottom line, the real concern is damage to their reputation. For this reason, the auction houses are obsessed with liability issues. As everyone knows the art market is unregulated. The only beacon of stability is the major auction houses because there is a public record of prices achieved at their sales. This gives the buying and selling public confidence in doing business with them. Otherwise, you’d be at the mercy of every dealer who liked to tell self-indulgent stories about their deal making acumen (and the highly exaggerated prices they probably never got).

If a crack authentication team was assembled, it would position Sotheby’s and Christie’s to accept tens of millions of dollars of works by Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Roy Lichtenstein, Jackson Pollock and others whose authentication boards have fallen by the wayside. While there would probably be an initial rush of owners anxious to take advantage of this new development, this would still be a steady source of revenue for the auction houses, as new works came out of hiding.

In addition, it would create a feeling of fair play in the art market. Despite the soaring auction prices as of late, there’s still a large group of wealthy investors who remain on the sidelines. They’re convinced that the art market is not a level playing field. Too many people believe the auction house proceedings are rigged because of the hidden language which has become de rigueur at the major sales. It’s often hard to decipher catalogue terms like “guarantee,” “third party interest,” and an asterisk which indicates the auction house itself has a financial interest in the picture. By including paintings which were genuine “since the day they were painted,” but somehow didn’t survive the politics of an art authentication board, it would go a long way toward installing confidence in the integrity of the art market.

New chapters for all...

I continued to follow the exploits of Alice Cooper and was amazed by how he was still touring and releasing new music. As rock stars continued to age, they took on a venerable quality. The key members of the Rolling Stones were approaching 80, yet there was serious talk of their going out on the road again. The public who grew up with the Stones, while getting older themselves, still felt a connection and were only too happy to continue to support their music. So too was the case with Alice Cooper.

Meanwhile, rumour had it that the editors of the Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné planned to publish an addendum, once the main project has been completed. Given the massive task ahead of them (they are currently preparing the next volume which will include work from 1979 and possibly beyond), it’s hard to predict when (and if) the addendum will happen. In theory, the book is likely to include those paintings which the Warhol estate never examined that slipped between the cracks. Given the chaotic nature of the Factory during the 1960s and early 1970s, there are plenty of candidates. And Alice Cooper’s red Little Electric Chair is certainly one of them.

One morning, I saw the name Shep Gordon appear on my phone’s screen. I immediately thought, I haven’t talked to Shep in a while… it must be important.

“Hi Richard,” said Shep.

“How’ve you been?” I responded.

“Good… Listen I just had an interesting trade offer. The manager of a contemporary artist, whose paintings bring in the millions at auction, offered to trade me for Alice’s painting.”

“What?” was all I could muster.

“Yeah, it turns out he’s a big fan of Alice’s and a big fan of the painting. In fact, he’s been following its story since day one. His manager proposed that he show me a few paintings and let me pick one. He also made it clear that it was mine to sell and he’d have no problem if I put it up to auction.”

“That’s incredible,” I said. “Who’s the artist?”

After disclosing his name, I quickly voiced my approval and said to Shep, “It’s a different way to go. But it gets the job done and at least the painting ends up going to someone who obviously loves it — which is pretty cool. It’s certainly a much better idea than having it cut up and sold as NFTs!”

“Agreed… I think I’m going to take the deal.”

Richard Polsky is the author of I Bought Andy Warhol and I Sold Andy Warhol (too soon). He currently runs Richard Polsky Art Authentication: www.RichardPolskyart.com

Read the previous instalment of the I Authenticated Andy Warhol series here.