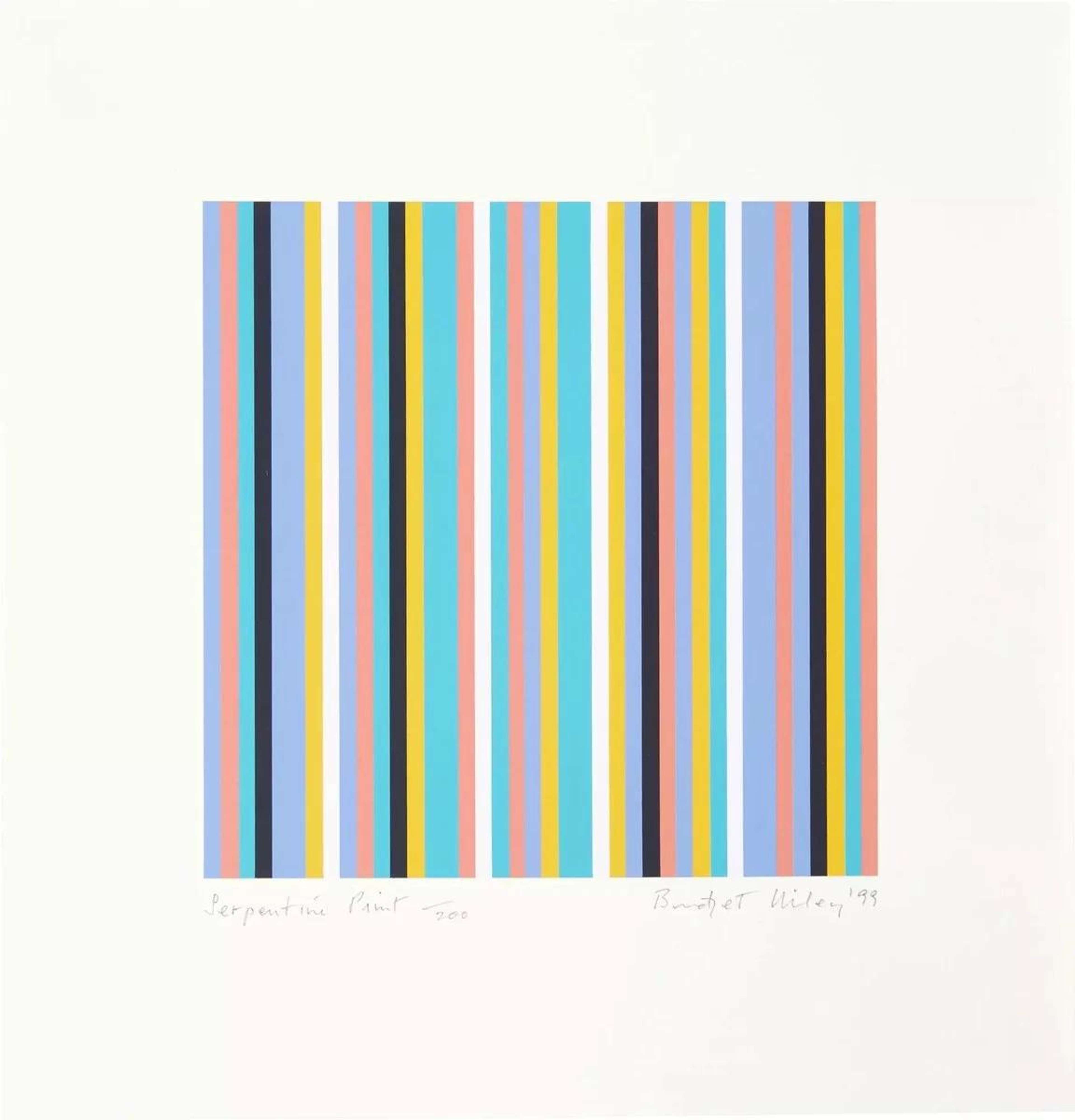

Serpentine © Bridget Riley 1999

Serpentine © Bridget Riley 1999

Bridget Riley

112 works

Once the frontrunner of the British Op Art movement, Bridget Riley is the creative genius behind a large body of dynamic, optically provocative artwork.

Read MyArtBroker's Bridget Riley Investment Guide In 2024.

Stunning onlookers for over 60 years, London-born Riley’s 1960s creations were largely monochromatic; in the 80s, the artist adopted a colour-based approach that referenced both a life-changing holiday to Egypt, and her long held love of Post-Impressionist art.

In this article we take a closer look at Bridget Riley’s career and her Top 5 most famous artworks.

image © Sotheby's / Pink Landscape © Bridget Riley 1960

image © Sotheby's / Pink Landscape © Bridget Riley 1960Pink Landscape (1960)

Born in South London in 1931, by 1958 Riley was working as a commercial illustrator at an advertising agency.

The same year, the artist-to-be attended an exhibition entitled The Developing Process, based on the art theories of influential art teacher and writer Harry Thubron.

Showcasing recent developments in European and American painting, the exhibition had such an enormous impact on Riley that she left her job.

Later attending Thubron’s summer school, she met the artist Maurice de Sausmarez, who encouraged her to study the art of French Post-Impressionist Georges Seurat.

Known for the iconic works Une Baignade, Asnières (1884) and Un dimanche après-midi à l’île de la Grande Jatte (1884-6), Seurat is associated with the Pointillist movement. Defined by its focus on colour theory and perception, rather than likeness, pointillism saw artists use ‘dots’ of block colour to convey a sense of their surroundings.

One of Riley’s earliest and most famous works, Pink Landscape (1960) is based on Seurat’s iconic Le pont de Courbevoie (1886).

Using a reproduction of Seurat’s iconic work as a guide, Pink Landscape sees Riley paint an impression of the hills outside the Italian city of Siena. In the image, she uses a different colour palette to Seurat, to awe-inspiring effect.

The painting marks a key stage in Riley’s artistic development: as soon as it was finished, she abandoned colour, only returning to it in the 1980s. Introducing the next ‘phase’ of her career, the work references the art historical basis of Riley’s unique and seminal take on non-representationalism and abstraction.

In 2016, a retrospective of Riley’s work that testifies to the French artist’s profound influence on her career – entitled Learning From Seurat – opened at London’s Courtauld Institute.

Movement In Squares (1961)

Perhaps the most iconic example of Riley’s work is Movement In Squares (1961). An emblem of what later became known as ‘Op Art’, the piece constitutes another stylistic and conceptual turning point in the artist’s career.

Following a trip to the 1960 Venice Biennale, Riley abandoned the more conventionally representational, pointillist style seen in Pink Landscape, opting in favour of the rigid, geometric forms of the Italian Futurists.

Re-tracing the dialogue between black, white, and colour, this illusionist work is testament to the Futurists’ influence.

Producing a variety of polychromatic hues despite its otherwise monochromatic composition, Movement In Squares comprises bold, hard-edged forms. Yet — as its title suggests — the work remains dynamic; two ‘fronts’ of geometric shapes meet to create a vanishing line that appears to suck these cuboid forms into its fold.

Blaze 1 (1962)

Blaze 1 is another of Riley’s most famous artworks.

An iconic piece painted towards the beginning of Riley’s career, it was the first to achieve international recognition, and comprises a concentric arrangement of circles, each filled with black and white ‘zigzags’.

When confronted with this dizzying image, you’d be forgiven for thinking there was a mathematical — or even scientific — bent to Riley’s painting.

Eschewing any theoretical approach to composition or colour, Riley’s work in this period is also indebted to her longstanding interest in French Post-Impressionist art and De Stijl — a Dutch abstract movement co-founded by Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg.

As is visible in this work, Riley applied the principles of Seurat’s Pointillism to the hard-edged forms of the ‘swinging 60s’. Breaking down areas of light and shadow into blocks, much in the way that Seurat did, Riley affirmed onlookers that her work was instinctual, not theoretical.

By 1964, and thanks in part to this image, the term ‘Op Art’ – short for ‘optical art’ - was coined by American sculptor Donald Judd.

Removing the ‘p’ from Pop Art, the term suggested the movement’s desire to rival its American cousin, and the likes of Andy Warhol – a figure loved by British art students of the day, such as David Hockney.

Later that decade, in 1967, Riley was included in the landmark Op Art exhibition The Responsive Eye, held at MoMA New York. Op Art had conquered America.

Image © Christie's / Cupid's Quiver © Bridget Riley 1985

Image © Christie's / Cupid's Quiver © Bridget Riley 1985Cupid's Quiver (1985)

Like Achæan (1981), Cupid’s Quiver (1985) is a vertically-orientated work inspired by a career-defining trip to Egypt that Riley made in 1979.

During the visit, Riley visited Cairo and the Nile Valley. There, she studied the tombs of the Egyptian Pharoahs at the Valley of the Kings — an archaeological site located just opposite Thebes, where at least 63 tombs and chambers once served as burial sites for the royalty and nobility of the Egyptian ‘New Kingdom’.

Stunned by the liveliness of these otherwise morbid spaces, Riley noticed that a single colour palette had been used throughout Egyptian society, in almost all aspects of social and cultural life. Here, she reproduces that same colour palette, bringing it into dramatic convergence with her trademark hard-edged forms.

Product of an overnight shift from black and white and back to colour — which Riley had not worked with since 1961 — the piece is not only one of Riley’s most famous, but one of her most expensive.

In March 2021, Cupid’s Quiver went under the hammer at Christie’s London. It realised £2, 242, 500, becoming the 8th most-expensive Riley work of all time.

Image © Christie's / Gaillard © Bridget Riley 1989

Image © Christie's / Gaillard © Bridget Riley 1989Gaillard (1989)

An assortment of coloured rhomboids – or ‘zigs’, as the artist calls them – Gaillard (1989) is characteristic of Riley’s later work.

Combining her love of colour and ‘optics’, the piece is testament to Riley’s constant innovation, as well as her enduring influence by Post-Impressionism and its many different ‘ways of seeing’.

Gaillard disrupts the viewing habits of its audience, questioning our ability to ‘read’ images simply, as we might do language.

Riley explains: ‘The colours' of such works […] are organised on the canvas so that the eye can travel over the surface in a way parallel to the way it moves over nature. It should feel caressed and soothed, experience frictions and ruptures, glide and drift […]. One moment there will be nothing to look at and the next second the canvas suddenly seems to refill, to be crowded with visual events.’

Many people have speculated that this image might have inspired Damien Hirst —who began exhibiting his artwork just a year earlier, in 1988 — to create his world-famous Spot paintings.

Browse our Bridget Riley prints for sale or get a valuation here.