Canaries

Landscapes

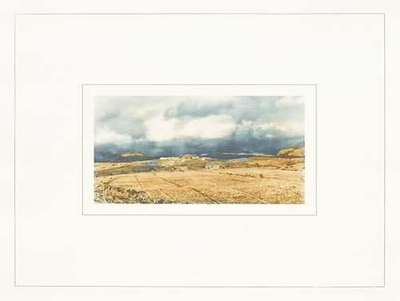

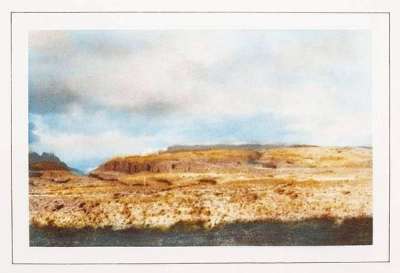

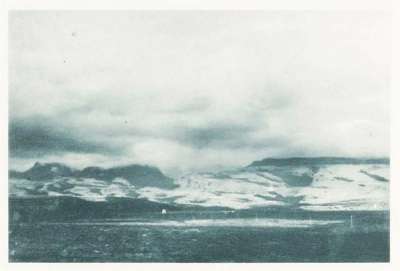

In Canaries Landscapes, Gerhard Richter turns his attention to the art historical trope of the landscape. Fascinated with cultural memory, he depicts a desolate and barren scene—the dramatic volcanic landscape of the Canary Islands —seemingly rendering it as the uncanny image of a forgotten, rugged prehistory.

Gerhard Richter Canaries Landscapes For sale

Canaries Landscapes Market value

Auction Results

| Artwork | Auction Date | Auction House | Return to Seller | Hammer Price | Buyer Paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kanarische Landschaften I - e Gerhard Richter Signed Print | 8 May 2025 | Van Ham Fine Art Auctions | £1,063 | £1,250 | £1,800 |

Kanarische Landschaften I - a Gerhard Richter Signed Print | 11 May 2024 | Nosbüsch & Stucke | £2,933 | £3,450 | £4,300 |

Kanarische Landschaften II - f Gerhard Richter Signed Print | 18 Jan 2024 | Van Ham Fine Art Auctions | £1,998 | £2,350 | £3,300 |

Kanarische Landschaften II (complete set) Gerhard Richter Signed Print | 22 Jun 2022 | Karl & Faber | £5,950 | £7,000 | £9,000 |

Sell Your Art

with Us

with Us

Join Our Network of Collectors. Buy, Sell and Track Demand

Meaning & Analysis

Gerhard Richter is one of the most significant German artists of all time. Well-known for his incredibly large and stylistically heterogenous ouevre, he has left few subjects untouched. From his historically-inspired paintings of newspaper photographs depicting Chinese Communist Mao Zedong, through to photorealistic paintings of still-life objects and architectural features, Richter runs the gamut of all-things contemporary. In this collection, entitled Canaries Landscapes, Richter turns his attention to yet another key artistic trope: the landscape.

In Kanarische Landschaften 1 - e (1971) and Kanarische Landschaften 1 – a (1971), we are party to an intensely detailed portrayal of a rugged, volcanic landscape. Both prints make use of the highly sophisticated heliogravure process, a transfer-based printing technique that allows Richter to combine an expressive touch and an eye for granular detail. Kanarische Landschaften II – f (1971) recalls Richter’s immense Atlas – a collection of photographs, newspaper clippings, and sketches the artist has compiled since the 1960s. In so doing, the photographic basis and origin of Richter’s art are once again laid bare.

Born in Dresden in 1932, Richter received formal artistic training at the Dresden Academy. Then under the purview of East German and Soviet authorities, the Academy limited its students to the production of fiercely ideological, socialist realist art designed to portray the glories of Communism. Opting to study under mural painter Heinz Lohmar, Richter was later exposed to a relatively free and cosmopolitan style of painting; but it was the artist’s aunt, who lived in allied-controlled West Germany, who was ultimately responsible for his denunciation of artistic conformity. Sending the artist excerpts from the photography magazine ‘Magnum’ every month, this aunt granted Richter privileged access to artistic developments taking place in Western Europe, and an immense body of photographic reference points for his artworks. When Richter was later granted permission to exhibitions in the West, he realised, in his own words, that ‘there was something wrong with my whole way of thinking’.