Keith Haring & Andy Warhol: A Friendship That Shaped Pop Art

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr / Andy Warhol and Keith Haring

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr / Andy Warhol and Keith Haring

Interested in buying or selling

Keith Haring?

Keith Haring

249 works

There are some moments in time that just seem to perfectly encapsulate a society’s zeitgeist, full of places and people that seem to have a finger on the very pulse of pop culture. This was the case in the effervescent world of 1980s New York, where two artists stood at the vanguard of a cultural revolution that would come to define an era.

Keith Haring – the emerging artist with his dynamic figures and bold public canvases – and the consummate Pop Art maestro Andy Warhol forged not just a friendship but a collaborative synergy that transcended their individual fame. The intertwining lives of Haring and Warhol, their camaraderie and mutual influence catalysed a new wave within the evolution of the Pop Art movement. Their story is one of a remarkable confluence of personality, talent and vision, resulting in timeless works that challenged conventions and reimagined what art could be.

Warhol's History of Mentorship

Warhol's collaborative spirit was pivotal in shaping the careers of many influential artists from the 1960s onward. In that decade, Warhol had already established a pattern of mentorship at his studio, The Factory. There, he worked with and supported a wide range of artists including Gerard Malanga and Isabelle Collin Dufresne, as well as a retinue of bohemian and counterculture figures known as his superstars. This group not only collaborated on Warhol's projects but also became central to the creative output and social dynamics of The Factory at large. This history of mentorship demonstrates Warhol's long-standing commitment to fostering talent and pushing the boundaries of art through collaboration.

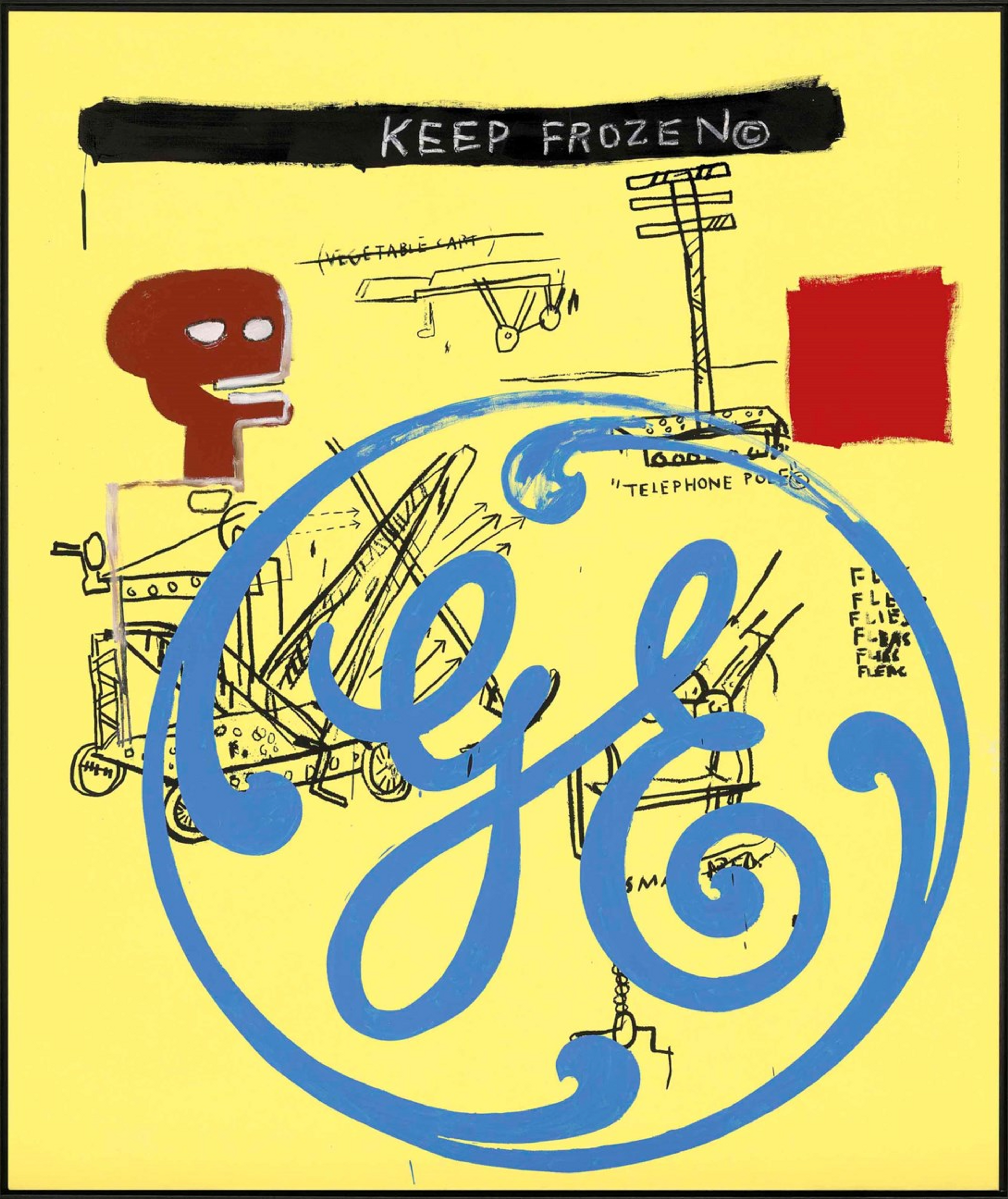

The fact that Warhol often acted as mentor due to his high standing in the art world is not to say that he did not benefit from many of these relationships. One of the most famous examples of this is his iconic 1980s partnership with Jean-Michel Basquiat, then an up-and-coming artist. Their collaboration was both a friendship and a creative exchange, jointly producing over 150 works. Warhol was impressed by Basquiat's speed and originality, and the two shared a bond that was part supportive and part competitive – especially as Warhol greatly feared becoming obsolete and was constantly on a quest for reinvention.

Warhol x Haring: Tracing the Evolution of the Pop Art Movement Through Two Visionaries

From early on in his career in the 1960s, Warhol was crucial for the development and consolidation of the Pop Art movement. Following a successful stint as a commercial artist, Warhol redefined popular culture with his art, using everyday objects and enduring images such as Marilyn Monroe’s likeness and Campbell's Soup Cans to challenge traditional art conventions. His experiments with silkscreening, performance art, filmmaking and video installations blurred the lines between fine art and mainstream aesthetics. Warhol's approach was revolutionary, making art accessible and relatable to the masses and cementing his status as the "Father of Pop Art".

Haring's impact on Pop Art unfolded differently, in a distinctly less glossy way. Beginning with spontaneous chalk drawings in New York City subways, these became a laboratory for Haring's iconic imagery such as the Radiant Baby, barking dogs and flying saucers. His bold lines and vibrant murals, often created in public spaces like hospitals and schools, carried potent political and societal messages. Haring's work, especially from 1982 to 1986, gained recognition for its energetic lines and movements. The activism present in his imagery also made profound cultural statements, particularly regarding homosexuality and AIDS awareness. Haring's rise to fame was distinctly grittier than Warhol's, reflective of the ethos of the 1980s.

Both artists pushed the boundaries of the art world by incorporating elements from everyday life and commentary on contemporary issues. Warhol's use of commercial goods and celebrity culture and Haring's street art aesthetics and activism both served to democratise art, making it more approachable and engaging for the general public. Their distinct contributions laid the groundwork for subsequent generations of artists and the continuing evolution of the Pop Art movement.

Image © Sotheby's / Keith Haring and Juan Dubose © Andy Warhol 1983

Image © Sotheby's / Keith Haring and Juan Dubose © Andy Warhol 19831982: The Beginnings of a Pop and Street Art Alliance

According to Warhol's diaries, the artists first met during one of Haring's shows at the Shafrazi Gallery in late 1982. At this point, Haring’s career was only starting, while Warhol was already considered a giant in his field. Impressed with the spontaneity of the dancing figures, Warhol then visited Haring in his studio, and a friendship emerged in 1983. The pair often hung out socially together, and Warhol had a significant impact on Haring's life by serving as a mentor. Haring credited Warhol as a major influence and early supporter of his career, and wrote in his diaries that “the biggest honour was the support and endorsement he bestowed upon me. By mere association he showed his support… I learned a lot of things from Andy in the five years we were friends. He prepared me for the ‘success’ that happened to me while I knew him, and taught me the ‘responsibility’ of that success.”

Over the next five years, Warhol and Haring exchanged many works and featured one another in their art. As a foundational figure of Pop Art, Warhol found in Haring—a trailblazer of street and graffiti art—a kindred spirit and a source of rejuvenation for his own work. The creative fusion between Warhol's established pop artistry and Haring's emerging street art flair illustrates the adaptive and inclusive nature of the Pop Art movement through the lens of two of its most visionary figures.

1986: Andy Mouse and the Pop Shop

In 1986, Haring opened the Pop Shop in downtown Manhattan, a radical endeavour that reflected his vision of art accessibility for all. The store was more than a retail space; it embodied Haring's artistic philosophy, selling his work and merchandise at low prices to make art democratic, and not just the preserve of galleries or the super wealthy. The shop's offerings ranged from affordable collectibles to original art pieces, making Haring's vibrant and socially conscious art part of everyday life.

Haring claimed to have had cold feet before its opening – the shop’s challenge of the elitism in the art world was criticised by many, but never by Warhol. The latter was convinced the idea was brilliant, and even created a line of t-shirts to support Haring in this venture. To thank Warhol, Haring created the series Andy Mouse – which depicts the artist as a figure of classic Americana in the style of Mickey Mouse, a character that Warhol himself had depicted several times. Andy Mouse engages with many motifs present in Warhol’s art, including money and media, while questioning what propels cultural stardom; it also borrows from Warhol’s own silkscreening technique, further solidifying the homage.

The legacy of the print series and Pop Shop is profound, challenging the elitism of the art world by proving that art could be commercial and still maintain integrity. It paved the way for a new approach to art consumption, appreciation, and distribution, influencing not just the art sector but retail as well.

1987: Warhol's death

In February 1987, Warhol unexpectedly passed away following complications from a gallbladder surgery. Haring goes on a deep reflection about Warhol’s life and career in his diaries, making it clear just how much the news affected him. He draws a comparison between Warhol’s death and the social life they shared together: “Andy had an incredible sense of timing. One thing I learned from going to a lot of parties and ‘social’ events with Andy was that he always arrived at the right time. He’d always arrive when the party was in full swing, but before the peak. In fact, his entry would often be the height of the party and the signal that the party had actually ‘started’. His exits were equally well timed. I would often catch him slipping out without saying goodbye. It was, of course, too difficult to try to say goodbye to everyone, so he’d just leave when nobody would notice and then people would slowly realise… He didn’t want his exit to signal the ‘end’ of the party, so he quietly slipped out when we least suspected it… mysteriously and with style. He left like he had left hundreds of parties… unnoticed leaving, but instantly missed; his absence both bewildering and unexpected. The party goes on, but something will be different. Andy is gone and I miss him already.”

The following year, Haring would be diagnosed with AIDS, at a time when the condition was practically a death sentence.

Their Joint Legacy and the Pop Art Movement

The joint legacy of Warhol and Haring within the Pop Art movement is a testament to their transformative impact on art and culture. Their friendship was iconic, with Warhol's recognition of Haring's talent and Haring's reverence for Warhol's trailblazing persona creating a powerful creative synergy. Together, they hosted events and supported each other on projects that left an indelible mark on the art world.

Warhol was instrumental in the Pop Art movement, using silkscreening to incorporate elements of consumerism and celebrity culture into his art. His style challenged traditional art conventions and redefined popular culture. Meanwhile, Haring took screen printing to new heights, blending graffiti with abstract and cartoon elements, which allowed him to mass-produce his work and make it even more accessible to a wider audience.

In 2024, the Museum Brandhorst in Munich hosted Andy Warhol & Keith Haring. Party of Life, the first comprehensive institutional exhibition dedicated to both artists. Running from June 28, 2024, to January 26, 2025, the exhibition explored the vibrant art scene of the 1980s, featuring over 130 works, including collaborations and pieces created with contemporaries like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Madonna. The exhibition attracted over 100,000 visitors within the first four months, underscoring the public's sustained interest in Warhol and Haring's contributions to art and culture.

Their collaborative works and individual contributions have left a lasting legacy, with both artists embodying the spirit of Pop Art through their innovative approaches to creation, graphic sensibilities, widespread dissemination and the contemporary social commentary embedded in their works. Their partnership continues to resonate today, embodying the Pop movement's ethos by merging high art with popular culture and social activism, forever altering the landscape of contemporary art.