Roy Lichtenstein: Pop Art's Intellectual

Still Life With Picasso © Roy Lichtenstein 1973

Still Life With Picasso © Roy Lichtenstein 1973

Interested in buying or selling

Roy Lichtenstein?

Roy Lichtenstein

293 works

Roy Lichtenstein is known for his ability to merge ‘high’ and ‘low’ art, often borrowing from comic books and romance novels. A titan of the Pop Art movement, he masterfully bridged the gap between commercial culture and fine art, challenging the conventions of the art world in the 1960s. His iconic comic strip-inspired paintings, marked by bold lines and Ben-Day dots, became emblematic of a new artistic dialogue. Lichtenstein's work delved into themes of imitation and mass production. Aside from that, however, he also looked toward the art historical canon for inspiration, often referencing artists such as Picasso, Mondrian, Monet and Cézanne.

Lichtenstein's Early Years

Lichtenstein's journey to becoming an intellectual pillar of the Pop Art movement began long before his comic-strip inspired works captivated the art world. As a youth, Lichtenstein was steeped in education, having attended the Dwight School in New York City – the motto of which is “Igniting the spark of genius in every child.” This formative period nurtured a broad curiosity that extended beyond the visual arts to encompass a deep love for music, notably jazz. He was part of a jazz band, and this passion would later inspire works such as the Aspen Winter Jazz Poster and the Composition series. This multidisciplinary interest laid the groundwork for his expansive creative language.

His academic pursuits led him to Ohio State University, a choice reflecting his commitment to a formal art education. The interruption of his studies by World War II did little to deter his intellectual growth; Lichtenstein's army tenure, initially earmarked for specialised training programs, eventually saw him serving in roles that utilised his artistic skills, such as a draughtsman and artist. Upon his return to Ohio State, Lichtenstein earned a Master of Fine Arts degree and began to impart his knowledge to others as an art instructor, a role he embraced intermittently over the next decade. This period was marked by a dedication to teaching and a continuous exploration of artistic styles and methods.

In 1957, a move back to upstate New York heralded a new chapter in Lichtenstein's career, both as an educator and an artist. It was during his tenure teaching at the State University of New York at Oswego that he started experimenting with Abstract Expressionism, a relative latecomer to the movement. This phase was also notable for his increasing incorporation of cartoon characters into abstract works, hinting at the iconic style he would later pioneer. Lichtenstein's final teaching position at Rutgers University coincided with a pivotal moment in his career. Here, he engaged with a circle of artists and intellectuals who shared his fascination with the intersection of pop culture and fine art, a collective curiosity that would propel him towards the breakthroughs that defined his contribution to Pop Art. Despite leaving Rutgers in 1963 following his rise to fame, the intellectual foundations laid throughout his early life and academic career profoundly influenced his art, teaching, and enduring legacy as a thinker and creator.

Lichtenstein’s Dialogue With the Art Historical Canon

In 1962, Lichtenstein focused on reproductions of masterpieces by seminal artists such as Cézanne, Mondrian, and Picasso. This bold act of homage was also a radical interrogation of the merits of art itself. Lichtenstein transformed these iconic works into his distinctive pop idiom, utilising his signature palette limited to primary colours to represent and reinterpret them. In doing so, he further challenged the sanctity of exclusively original works, and the boundaries between high and low culture. Lichtenstein's dialogues with established masters questioned the very nature of artistic creation, authorship, and the authenticity of art in a mass-produced world. He has often been accused of plagiarism for this practice, but it has always been a strong tradition in art, as illustrated in the 1963 work Femme D’Alger. Here, Lichtenstein isolates and reinterprets one of the figures in Picasso’s Les Femmes D’Alger – which itself was inspired by Women Of Algiers by Eugène Delacroix.

Mondrian had a particular influence on Lichtenstein, especially with regards to the primary colour palette that would come to define Lichtenstein’s most famous works. Throughout his career, Lichtenstein would return to Mondrian’s work, such as in Non-Objective I. The work’s own title addresses some of the questions raised by critics on Lichtenstein’s validity as an artist and intellectual: it engages with Mondrian's pursuit of a universal beauty through minimalist abstraction, aiming for "objectivity." It humorously hints that this piece by Lichtenstein is, indeed, not an actual Mondrian; it exists neither as the original item nor does it seek to embody objectivity.

Lichtenstein also frequently engaged with Monet's oeuvre, reinterpreting the Impressionist's masterworks with his distinct Pop Art lexicon. His first two print series, Haystacks and Rouen Cathedral from 1969, both reference the work of Monet. These replicate the French master’s obsession with changing colour and light, but by replacing Monet's nuanced brushstrokes with meticulously placed Ben Day dots and vivid colours, Lichtenstein transformed the delicate dynamics into striking Pop visuals. Decades later, in 1992, Lichtenstein would again converse with the Impressionist’s work in the series Water Lilies and Nymphéas. This series of six screen prints on stainless steel captures Lichtenstein's lasting interest in the dynamic between realistic representations of nature and the inherent artificiality found in traditional nature painting styles. By reducing Monet's water lilies to their fundamental visual components, Lichtenstein redirects attention from the broader scene to the precise elements it comprises.

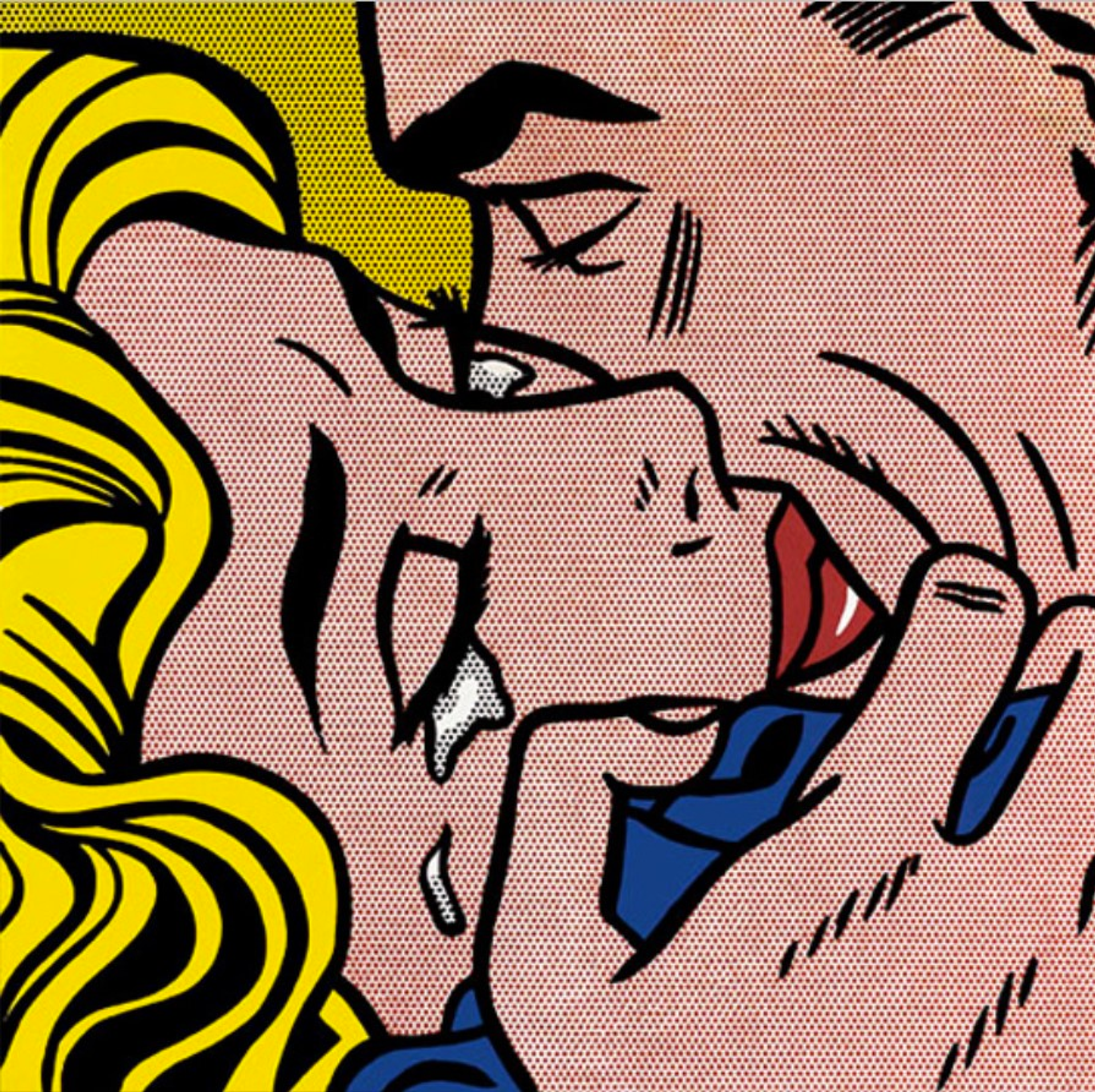

In the 1970s, Lichtenstein continued to explore and pay tribute to the foundational movements and luminaries of the history of art through his prolific output of prints and paintings. This period saw the creation of his Entablature series, such as Entablature V (1976) housed in Tate, London, drawing inspiration from the architectural motifs of neo-classical edifices. Alongside these, Lichtenstein's Still Lifes series emerged, where he reinterpreted the classical subject by delving into Cubism, often nodding to the works of Picasso and others. The mid to late '70s marked a new venture with a series that honoured Surrealist masters like Max Ernst and Salvador Dalí. Lichtenstein’s reverence for Picasso is also well-documented, as in the works Woman With Flowered Hat and Still Life with Picasso (Homage to Picasso), done after the Spanish artist’s death. Finally, in 1992 he created Bedroom at Arles, an oil and Magna on canvas painting based on the Bedroom In Arles series of paintings by Vincent van Gogh. This is the only quotation of another painting that Lichtenstein did of an interior.

Lichtenstein's engagement with these art historical references was far from mere replication. His work critically navigated the terrain between homage and commentary, addressing the complex dynamics of art's commodification within the burgeoning consumer culture of his time. By recontextualising iconic artworks within his distinctive style, Lichtenstein invited a reexamination of the original pieces, highlighting their transformation and assimilation into the fabric of popular culture.

Lichtenstein and the Questioning of the Art Process

Lichtenstein's philosophical engagement with the art-making process manifests profoundly through his work, challenging traditional views on the essence of artistic creation. His art often serves as a commentary on the processes and conventions of both the past and his contemporary art world, inviting viewers to reconsider their perceptions of the creative process of art. One early example is Lichtenstein's Portrait Of Madame Cézanne, which is a quotation of painter and art historian Erle Loran's diagrammatic analysis of Cézanne's portrait of his wife. Exhibited at Lichtenstein's first solo show in Los Angeles, this piece sparked debate over the nature of art and its reproduction, highlighting Lichtenstein's knack for layering complexity through appropriation. By transforming an analytical diagram into a piece of art, Lichtenstein blurs the lines between academic study and artistic creation, prompting a reevaluation of art's essence and the value of interpretation versus original creation.

Another pivotal series that probes the art-making process is Lichtenstein's Brushstroke series, where he isolates and monumentalises the brushstroke—an elemental act of painting. This series abstracts the brushstroke, rendering it in his iconic Ben-Day dots and lines, thus stripping it of its traditional role as a carrier of emotion and technique. Through this, Lichtenstein emulates the gestural brushwork of Abstract Expressionism, questioning the authenticity and originality of the painter's mark in an era dominated by mass-produced images. The Bull series further exemplifies Lichtenstein's interrogation of artistic process and evolution. Inspired by Picasso's progressive abstraction of a bull, Lichtenstein embarks on a similar process, transforming the figure of a bull from a recognisable form into a series of elements. This sequential simplification serves as a commentary on the nature of representation and abstraction, as well as the processes of seeing and understanding art. Here, Lichtenstein positions his own work within a broader dialogue about the reduction of forms and the essence of visual representation.

Through these examples—each questioning and redefining conventional artistic processes—Lichtenstein's work remains a critical lens through which we can examine the complexities of creation, representation, and the ongoing dialogue between past and present artistic practices.

Questioning Creativity and Originality: Lichtenstein's Legacy

Lichtenstein's legacy as Pop Art's Intellectual is indelibly marked by his deep engagement with the process of artistic creation. His work, characterised by its bold interrogation of art historical narratives and its embrace of popular culture, positions him as a pivotal figure in the discourse on the value and meaning of art in the modern era. Beyond the vibrant canvases and the iconic Ben-Day dots, Lichtenstein's strength lies in his approach to art-making—a constant exploration of themes, techniques, and perspectives. His substantial teaching career further underscored his intellectual pursuits, allowing him to share his insights and inquiries with the next generation of artists. Through his teaching, he nurtured a dialogue that extended beyond the classroom, fostering an environment of critical examination and creative exploration. His own explorations were deeply informed by his engagement with art history, as seen in his works that directly dialogue with masters. Lichtenstein's art thus became a confluence of reverence and critique, paying homage to these figures while simultaneously questioning the sanctity of their works and the processes behind their creation.