Banksy’s Christmas Murals – Unwrapping Hard Truths Since 2002

Queen's Mews ⓒ Banksy 2025

Queen's Mews ⓒ Banksy 2025

Banksy

270 works

Christmas sells the age-old story of goodwill to all men. Banksy has always disrupted it. Over more than two decades, the maverick street artist has returned to the festive season as a moment of deliberate tension – a time when faith and togetherness are most loudly rehearsed, and therefore most starkly exposed when they fail. Banksy uses Christmas to introduce friction, placing idealised narratives under pressure and allowing their contradictions to surface.

What emerges is a throughline, using Christmas as a site of intervention. From his temporary retail hijacks to politically charged murals, Banksy’s festive works consistently ask the same question: what do we really have to believe in?

Hijacking Christmas With Santa’s Ghetto, 2002-2007

Before Banksy’s Christmas interventions appeared on public walls, they appeared in shopfronts. Santa’s Ghetto ran intermittently between 2002 and 2007 as a temporary, Christmas-only project staged in improvised locations across London, before concluding in Bethlehem. Framed as a squat-style art concept store, it embedded itself directly within the seasonal shopping experience.

Operating under the Pictures on Walls umbrella, Santa’s Ghetto brought together artists from the street and underground art scenes, presenting work that often hadn’t been shown elsewhere and pricing it to remain relatively accessible. Its power lay in placement rather than scale. By occupying high-footfall retail zones in December, the project mirrored the language of festive consumption while quietly undermining it.

Banksy used Santa’s Ghetto as a proving ground. Across iterations in Shoreditch, Carnaby Street, Charing Cross Road, Soho and Oxford Street, the project blurred the boundary between exhibition, retail, and intervention. The presence of media attention and celebrity visitors only sharpened the contradiction between countercultural intent and mainstream visibility.

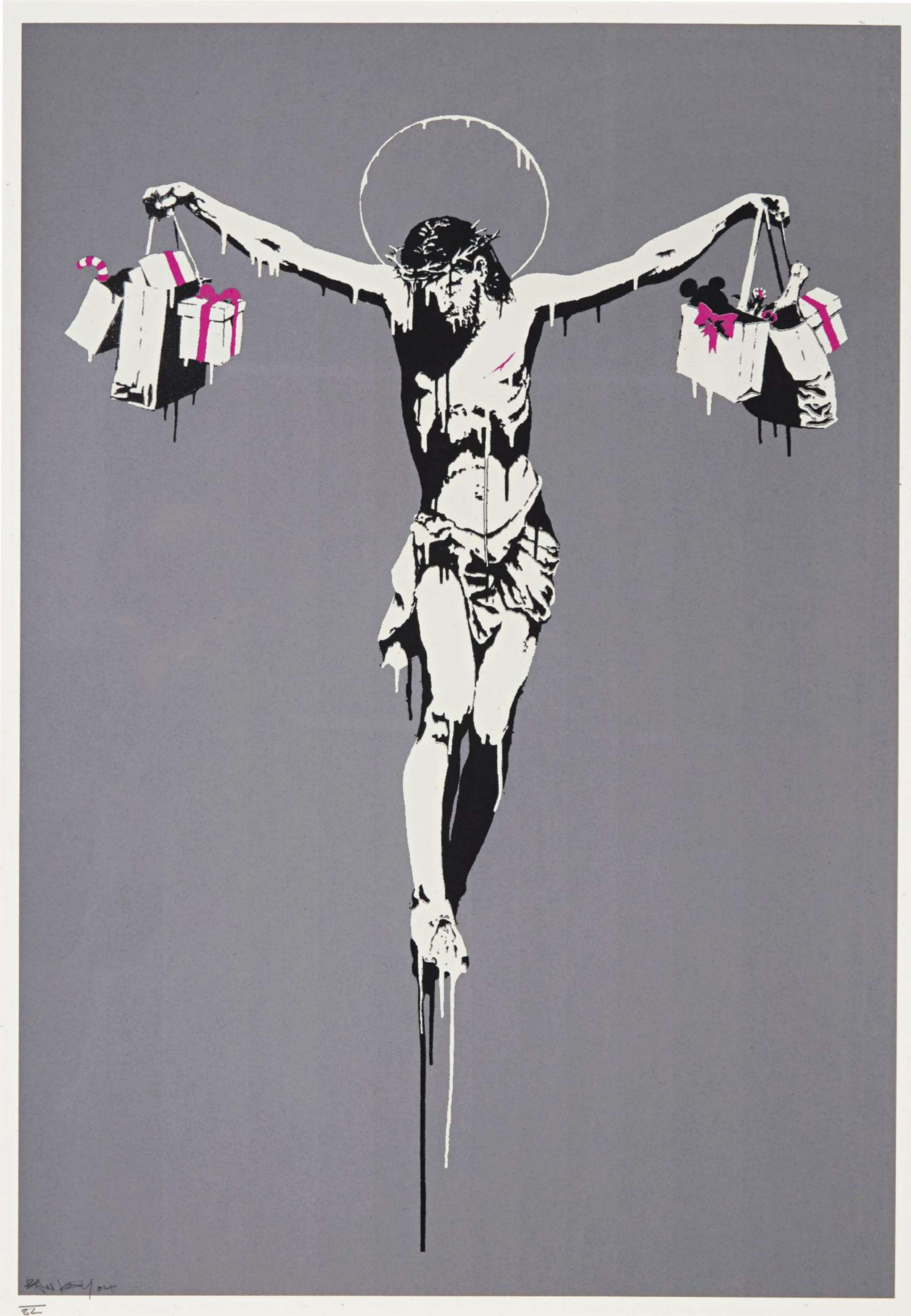

It was within this context that Banksy released works such as Christ With Shopping Bags. Seen through Santa’s Ghetto, the image functions less as a standalone provocation and more as part of a broader strategy: repurposing Christmas iconography to expose its commercial realities in the 21st century.

Season’s Greeting © Banksy 2018

Season’s Greeting © Banksy 2018Port Talbot - Season’s Greeting Shows A White Christmas Turned Grey in 2018

In December 2018, Banksy returned to the Christmas season with Season’s Greetings, painted on a garage wall in Port Talbot, South Wales. From one angle, the mural appears benign: a child catches falling snowflakes on his tongue. From another, the illusion collapses. The ‘snow’ is ash drifting from a burning skip around the corner.

The work demands movement. Viewers must physically reposition themselves to understand it, turning perception into participation. In doing so, Banksy literalises a familiar concern within his practice: the danger of accepting surfaces at face value.

The mural quickly drew thousands of visitors, transforming a residential street into a site of pilgrimage. Protective coverings and crowd management followed, reinforcing a familiar paradox – a work critiquing environmental harm simultaneously becomes a cultural asset in need of preservation.

At Christmas, a season associated with purity and renewal, Banksy instead presented contamination. Festive innocence gives way to industrial reality, and the act of looking becomes inseparable from the act of reckoning.

Birmingham Reindeer Mural © Banksy 2019

Birmingham Reindeer Mural © Banksy 2019Birmingham Reindeers Expose the Homelessness Epidemic in 2019

Banksy’s 2019 Christmas mural in Birmingham remains one of his most direct seasonal statements. Painted on a brick wall in the Jewellery Quarter, the mural depicts two reindeer in mid-flight. A bench placed below completes the illusion, transforming it into Santa’s sleigh.

The sleigh, however, is occupied by a homeless man named Ryan. In a video shared by Banksy, passers-by are shown offering food, a hot drink, and small gestures of care – unsolicited, but not unnoticed.

The intervention collapses fantasy into reality. Christmas generosity is no longer abstract; it is tested in real time, on a real street, with a real individual. The work exposes the gap between seasonal rhetoric and structural neglect, using Christmas imagery not to soften the message, but to sharpen it.

Interrupting the Nativity with The Scar of Bethlehem in 2019

Later that same month, Banksy unveiled The Scar of Bethlehem at the Walled Off Hotel, overlooking the Israeli separation barrier. The installation reimagines the nativity scene, complete with Mary, Joseph, and the infant Jesus. In place of the guiding star sits a bullet hole torn through the concrete wall behind them.

The symbolism is stark. Christmas, often framed as a story of peace originating in Bethlehem, is here overshadowed by violence and division. Wrapped gifts sit in the foreground, their presence unable to neutralise the rupture above.

Installed within a city defined by geopolitical tension, the work resists mythologising. Instead, it situates the Christmas narrative within contemporary conflict, reinforcing Banksy’s long-standing engagement with Palestine and his insistence that moral stories cannot be divorced from political reality.

Mother Andy Child © Banks 2024

Mother Andy Child © Banks 2024A Disturbed Madonna Appears in Mother and Child in 2024

In December 2024, Banksy returned to Christian iconography with Mother and Child, revealed via Instagram rather than as a street mural. The image depicts a veiled woman breastfeeding an infant. Embedded in her chest is a rusted pipe that reads visually as a bullet wound, with discoloured liquid trailing downward.

The intimacy of the scene is unsettled by injury. The maternal bond – typically associated with protection and nourishment – is rendered fragile. The child gazes upward, seemingly unaware of the harm sustaining him.

Echoing earlier works such as Toxic Mary, the piece extends Banksy’s interrogation of faith, power, and institutional failure. Released during the Christmas period, it complicates narratives of innocence and salvation, suggesting that damage is often embedded within systems meant to offer care.

Queen's Mews © Banksy 2025

Queen's Mews © Banksy 2025Children Stargazing in Queen’s Mews, London, 2025

On Monday 22 December 2025, Banksy claimed authorship of a new street artwork in Queen’s Mews, near Notting Hill. Reminiscent of his earlier oeuvre, the work depicts two children in their winter coats and woolly hats, lying down and gazing up towards the sky. The older girl in the background points upward, while the smaller boy in the foreground follows her gaze.

It appears the children are looking towards something we can’t quite see — perhaps a nod to the vivid imagination of childhood that is so often heightened at this time of year. Childhood innocence is a recurring trope in Banksy’s work, frequently used to heighten the emotional contrast between vulnerability and the harsher social realities that sit beneath his most outwardly tender imagery.

Images shared on Banksy’s official website and Instagram show the children painted above a row of small garages, with an overflowing skip framing the scene. As Banksy has demonstrated in earlier works such as Every Little Helps, No Ball Games, Bomb Love, Jack and Jill, and others, children possess a unique ability to cut through the noise adults fixate on. Here, despite their underwhelming surroundings, the two figures look upward towards something greater — a marked contrast to the sharper cynicism of his Royal Courts of Justice piece, and a work that closes 2025 with a note of optimism rather than irony.

There has also been speculation around a second, unclaimed work using the same stencil beneath Centre Point on Tottenham Court Road.

Our Banksy specialist, Jasper Tordoff's, take: “There’s an unmistakable echo of Girl With Balloon: the outstretched arm, the childlike simplicity of the gesture, the suggestion that meaning lives just beyond reach. A potential Christmas reading is hard to ignore. A lone star, appearing above a rough, almost forgotten building, carries clear connotations of the Star of Bethlehem. If the “star” isn’t celestial but artificial - a city light, a crane beacon - then the work flips from gentle hope to quiet indictment. The gesture becomes misdirected reverence. Children gazing upward at a manufactured light. If this is a corrupted Star of Bethlehem, then the message is bleak: the sacred has been replaced by the functional; wonder by utility; belief by branding. We still perform the gesture of faith, but the object has changed. Banksy often works best when the mockery is barely perceptible. The question isn’t do you believe? But what are you actually looking at when you think you’re believing?”