The Hidden Shift: What’s Really Driving Collectors Away From The Auction Room?

© MyArtBroker

© MyArtBrokerLive TradingFloor

“The title of our panel today is The Hidden Shift: What’s really driving collectors away from the auction room?”

With that, Market Editor Sheena Carrington opened a conversation that challenged an easy narrative: that confidence in the art market is fading.

Confidence Hasn’t Disappeared in the Secondary Art Market – It’s Moved

For Sheena and her fellow panellists – MyArtBroker Managing Director Charlotte Stewart, Head of Sales Jess Bromovsky, and Sales Director Louisa Earl – confidence has not disappeared from the secondary market. It has moved. Private sales are up, digital buying is normalised, and collectors now move fluidly between platforms, channels and advisers. The auction room, once the market’s centre of gravity, has become just one room among many.

When the Auction Room Lost Its Monopoly

To understand this “hidden shift”, Charlotte went back to 2008: “I started in the art market in 2008, on a print magazine – so, you know, the absolute opposite of the kind of world that we now inhabit at MyArtBroker.”

Back then, high-end magazines and thick catalogues were central touchpoints. Collectors were less digitally native; discovery was carefully curated; and “being in the room” at auction still signalled access, spectacle and status.

By around 2015, that model began to crack. Charlotte recalled heated debates about cutting catalogue budgets by as much as 75% and diverting spend into digital marketing and online-only sales. The idea that serious collectors would bid online was met with disbelief – even though many were already buying works they had never seen in person. The room was already losing its monopoly on the transaction.

How Covid Pushed the Art Market Online

If the 2010s were a slow evolution, Covid was the accelerant. “Had Covid not hit, I’m not sure we would have seen the digital innovation that was on. Everything changed,” Charlotte said. Auction houses had to digitise almost overnight; smaller, digital-first platforms such as MyArtBroker were suddenly structurally advantaged.

Inside the auction houses, routines were transformed. Teams could no longer gather around works; access was restricted; collaboration shifted onto video calls; and, as Jess noted, “how important good images were” became painfully obvious. For collectors, trust had to stretch further. As Louisa put it, “People couldn’t come and see the artworks in person… the trust level really had to increase at that point.”

Covid didn’t start the move away from the auction room, but it normalised the behaviours – remote viewing, online bidding, screen-based transactions – that now underpin the market.

The Auction Room as Theatre in a Slower, Digital-Led Era

Despite this shift, the panellists were clear that the auction room has not become irrelevant – particularly at the very top end.

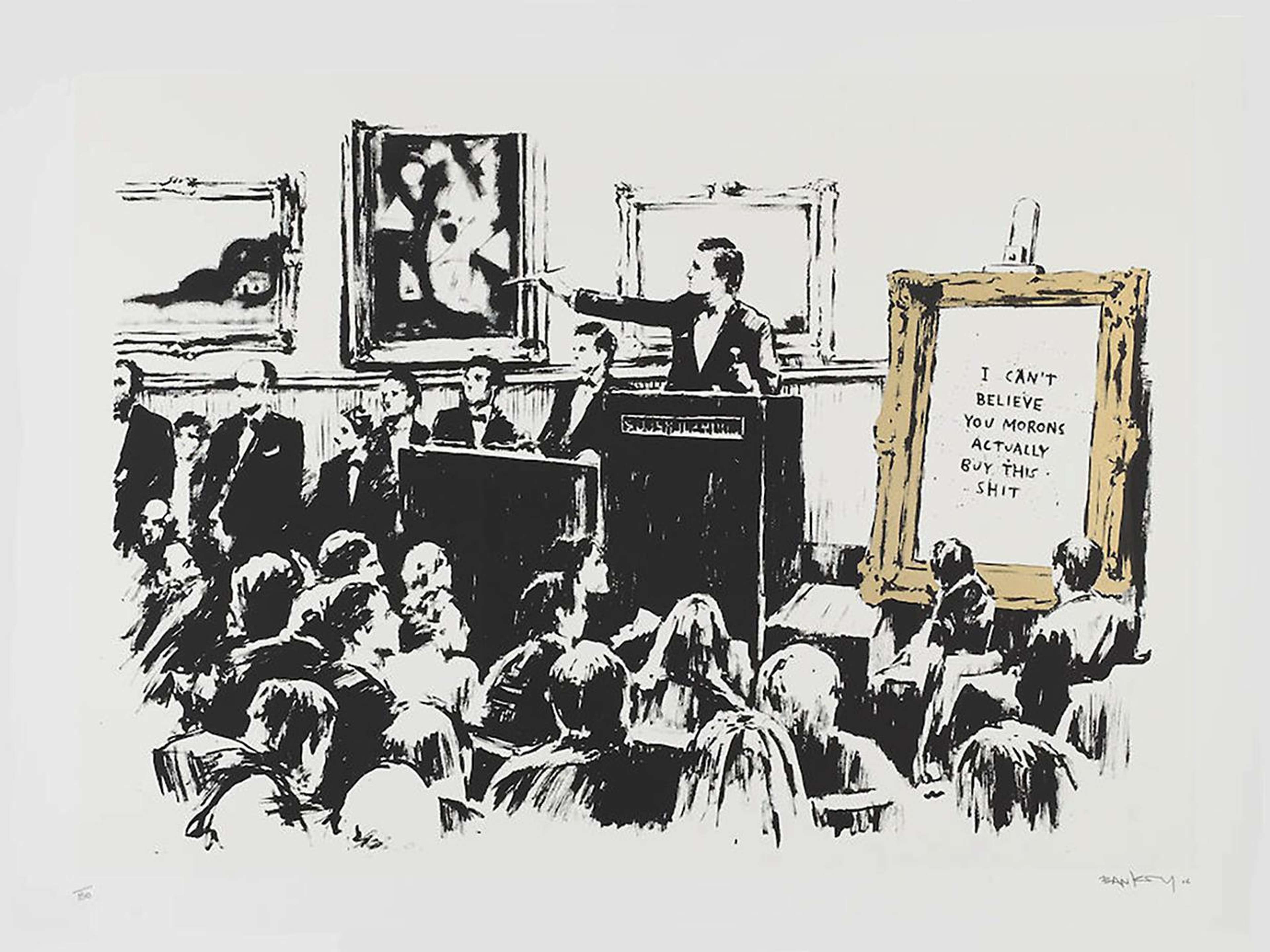

“These rooms are full,” Charlotte said of evening sales. “Watching a great auctioneer work is incredible… the theatre hasn’t disappeared… masterpieces that might have been in private collections for over thirty years come to market for the first time. That deserves a spectacle, that deserves a theatre. It’s very gladiatorial. It’s incredibly exciting.”

What has changed is how that spectacle works. Online bidding has become, in Louisa’s words, a “fourth platform”. The auctioneer now has to perform to the room, the phones, and unseen bidders on laptops and apps: “It’s a different element of showmanship where you can’t read the faces of the people behind the camera.”

The practical impact is measurable. “Sales used to do 60 lots an hour. Now they do more like 30 or 40 lots an hour, because the auctioneer is having to give that person behind the screen a chance to respond,” Louisa explained. “It’s not as exciting… but you need to be able to keep their attention, entice them, make sure that they really know what’s happening in the room in order to make sure that they’re bidding at the level that they want to bid at as well.”

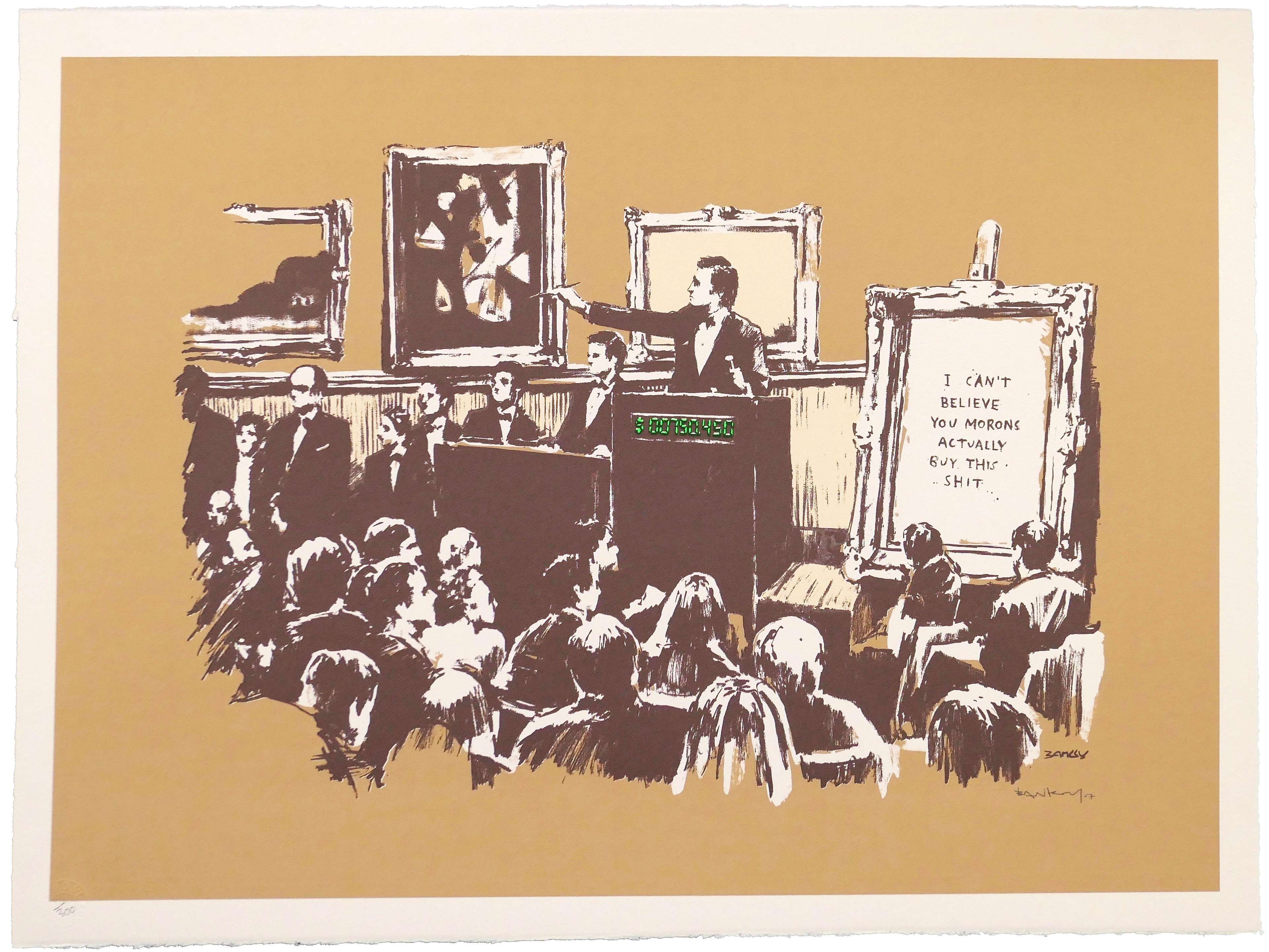

In the print market, the psychology has also changed. With more data available and larger edition sizes, collectors are less likely to be swept away by pure adrenaline. “If the price goes too high, you should be equipped with the knowledge to know… there are another potentially 149 of that edition,” Charlotte noted. “In its very essence, auction is not necessarily the right route for selling prints in my opinion.”

Why Private Sales Are Up: Efficiency, Control and Discretion

Against this backdrop, private sales have taken on a more prominent role, particularly in the print and mid-market space. As Sheena noted, private sales are up around 14% year on year, with both originals and editions increasingly trading away from the rostrum.

Asked why more collectors are choosing private sales over the public spectacle of the auction room, Jess highlighted three things: efficiency, control and discretion. With prints, where comparable data is plentiful, “you know what the value of the print should be, even if it’s a range,” she said – and that value can be agreed in advance rather than discovered under the hammer. Timing is flexible: sellers do not have to wait months for a relevant sale, and buyers do not have to sit through 300 lots to secure one work.

For sellers, discretion is crucial: “If it goes to auction and it’s an edition… if it doesn’t sell, that can really affect its resale… Whereas on the private sales market… it can be incredibly discreet. You can sell it without anyone knowing.”

Louisa pointed out that even auction houses are building this desire for certainty into their own structures: guarantees, absentee bids and priority bidding all provide sellers with more predictable outcomes. The psychology is the same as private sale – managing risk, rather than gambling on the night.

How Risk and Data Are Shaping the New Hybrid Collector

This shift towards private sales and structured outcomes is part of a broader psychological move. “Globally, people have become more risk averse since Covid because of all the shifts economically and politically we’ve seen across the world,” Louisa observed. Many collectors now want to know roughly what a work will sell for, when it will sell, and whether they really need to ship it halfway across the world.

At the same time, collectors have become more “hybrid”. MyArtBroker’s Collector Survey found that respondents use three to four platforms on average to buy and sell art, and 70% use social media such as Instagram and TikTok to discover artists and works. For Louisa, the modern collector is someone who might walk into a high street gallery, check prices on Artsy or Artnet on their phone, and then call a specialist like Jess for a second opinion.

The traditional “one advisor” model is being replaced by a more fluid relationship between data, platforms and specialists. “It’s become more of a sharing of information,” Louisa said, “rather than… advisors or people in the market becoming the gatekeepers of the information to pass on to private collectors.”

Yet the human touch point remains crucial. “What’s really lovely is there’s still that human touch point where once they’ve looked at that data, they will still send you a message and say, ‘Hey, what do you think of this?’” Jess added. Advisory hasn’t disappeared – it has been redefined.

Generational Wealth Transfer and the Role of Expertise

A recurring theme in today’s market commentary is generational wealth transfer – and the question of how younger, more digitally fluent collectors will behave when they inherit or build collections at scale.

Charlotte was keen to separate the different tiers of the market. “I think this is one of those topics which I feel like is talked about so much at the moment… and I think it’s drastically different depending what value level you’re talking about and what category you’re talking about.”

At the top end, traditional advisors are still central. “When we were putting content together back at Christie’s in 2010, proposals for big collections were 50/50. You were either talking to an advisor directly… or the client themselves. That has dramatically changed. Now proposals are written with the first decision maker – ‘Will I take this to my client and propose this is how we take this to market?’ – is usually an art advisor.”

By contrast, MyArtBroker’s survey suggests that a high proportion of print collectors say they do not use a formal advisor. But that does not mean they are operating without expertise. They are leaning on platforms, specialists and data tools in different ways.

Crucially, Charlotte argued, this is precisely the moment to double down on human expertise: “We’re building a business for the future. We’re building products that we hope will outlast us… but it’s really important that we actually double down on human expertise right now because we have an aging generation who are consigning extraordinary collections.”

“If we decide that this market can be run without expertise and connoisseurship, people will lose trust in it very, very quickly,” she warned. “You’ll find thirty years on, you’ve got people that have discovered work digitally trying to transact in a market where they haven’t got human expertise at their fingertips and making mistakes and feeling like it’s unanswerable because they haven’t got that expertise.”

Prints as the Market’s Most Revealing Pressure Point

If transparency and data now shape collector behaviour, the print market is where their limits become unmistakably clear. As Jess noted, auction results for the same edition often look contradictory: a print might sell for £30,000 one year, £15,000 a fortnight earlier, and £20,000 somewhere in between. “People have that data,” she said, “but they don’t understand why it is.”

The reasons sit in the micro-details: condition, provenance, edition history, and narrative. A perfect example, Jess explained, is the Dorothy Lichtenstein estate sale. Prints from that sale outperformed identical impressions sold months earlier: “Because it doesn’t have that same provenance, it doesn’t sell for the same amount.”

Louisa pointed out the same pattern with David Hockney’s Arrival of Spring. A single-owner sale generated record-breaking £400,000 prices, but fresh estimates for the same works still sit around £100,000–£150,000. You cannot apply a headline number universally.

For Charlotte, this is the clearest illustration of her “macro versus micro” framework – or what she often calls “clicks and connoisseurship, technology and people.” Digital tools can provide the macro: a fair, data-driven price band. But the micro – those subtle factors that specialists see after years of handling near-identical prints – cannot be automated. “Even a collector who’s been collecting for thirty-five years,” she said, “hasn’t seen as many impressions as these two have.”

Prints, then, are both accessible and complex: transparent enough for new entrants, yet rich enough to require specialist guidance. Precisely because of that tension, they have become, in Charlotte’s words, “a more complicated and therefore more exciting category” – a gateway that invites collectors in, while reminding them why human expertise remains indispensable.

Beyond Investment: Storytelling, Emotion and Where Confidence Lives Now

Throughout the discussion, storytelling and emotion kept surfacing as the real drivers behind collecting. Data and investment thinking are now normal parts of the conversation, especially in prints, where price histories are easier to track. But as Louisa put it, “it’s the story… that can really capture someone’s attention about an artwork, an image, an artist.”

Estate sales, single-owner collections, matching edition numbers – all of these create narrative layers that sit beyond pure financial logic. “Ultimately, at the end of the day, people love art and culture and heritage because of the storytelling,” Louisa said. “That’s never going to go away, no matter how much things cost.”

For Charlotte, the future lies in letting technology handle the tedious parts – cleaning up “dirty data”, collating information, making fair pricing easier to see – so that collectors can focus on what they actually enjoy: talking to people, learning, and falling for works. She even predicts that “the next generation in particular will want more human connection… particularly when it comes to that very emotive point about how essentially we fall for a narrative.”

As Sheena closed, she returned to the central thesis: confidence has not vanished from the secondary art market; it has shifted. It now lives wherever collectors can find clarity, context and conversation – whether that is an evening sale, in a discreet private transaction, or on a digital platform that blends clicks with connoisseurship and keeps human expertise firmly in the frame.