Influences

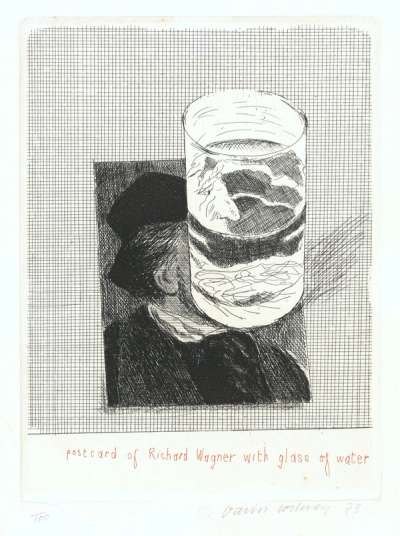

From Picasso to Auden, Wallace Stevens to Wagner, David Hockney’s oeuvre references his influences and idols frequently. In these prints, Hockney leaves his viewer in no doubt about their significance, whether that is in the form of a seated portrait, copycat studies, or ekphrastic inclusions of their art into his own.

David Hockney Influences For sale

Influences Value (5 Years)

With £205370 in the past 12 months, David Hockney's Influences series is one of the most actively traded in the market. Prices have varied significantly – from £564 to £47968 – driven by fluctuations in factors like condition, provenance, and market timing. Over the past 12 months, the average selling price was £12835, with an average annual growth rate of 3.9% across the series.

Influences Market value

Auction Results

| Artwork | Auction Date | Auction House | Return to Seller | Hammer Price | Buyer Paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Homage To Michelangelo David Hockney Signed Print | 24 Jan 2026 | Phillips London | £5,950 | £7,000 | £9,500 |

House Doodle David Hockney Signed Print | 15 Oct 2025 | Rago | £4,675 | £5,500 | £7,500 |

Artist And Model David Hockney Signed Print | 15 Oct 2025 | Rago | £22,100 | £26,000 | £35,000 |

The Student David Hockney Signed Print | 7 Oct 2025 | Lyon & Turnbull Edinburgh | £7,650 | £9,000 | £12,000 |

Postcard Of Richard Wagner With A Glass Of Water David Hockney Signed Print | 18 Sept 2025 | Phillips London | £2,975 | £3,500 | £4,900 |

Myself And My Heroes David Hockney Signed Print | 15 Jul 2025 | Sotheby's New York | £4,675 | £5,500 | £7,500 |

Man Ray David Hockney Signed Print | 27 May 2025 | Bonhams Cornette de Saint Cyr | £2,635 | £3,100 | £4,300 |

Maurice Payne David Hockney Signed Print | 3 Dec 2024 | Bonhams Knightsbridge | £2,550 | £3,000 | £3,850 |

Sell Your Art

with Us

with Us

Join Our Network of Collectors. Buy, Sell and Track Demand

Meaning & Analysis

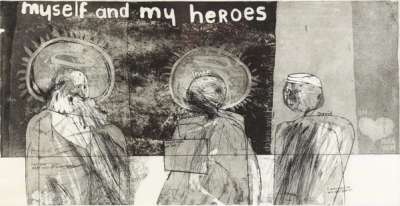

As captured in his Influences series, Hockney has always paid homage to his artistic inspirations, from Picasso to Auden, Wallace Stevens to Wagner. Beginning with one of his earliest prints, dating from 1961, when he was still a student at the RCA, we see Hockney paying homage to figures such as Walt Whitman and Gandhi, placing himself side by side inMyself and My Heroes in order to acknowledge his debt to them and their ideas. But while many may have expected him to leave such overt references to his influences behind upon leaving art college, Hockney has always included the figures that shaped his work – from the artistic to the musical to the literary – often placing them front and centre so the viewer is left in no doubt about their importance to this artist’s work.

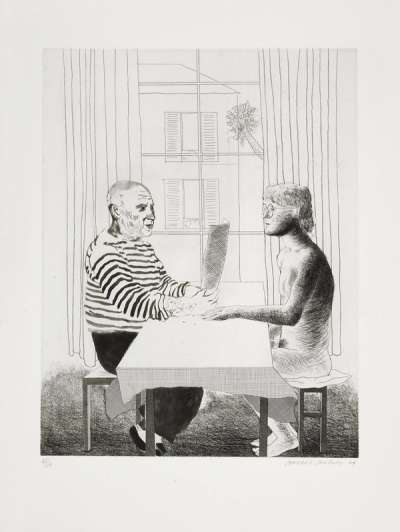

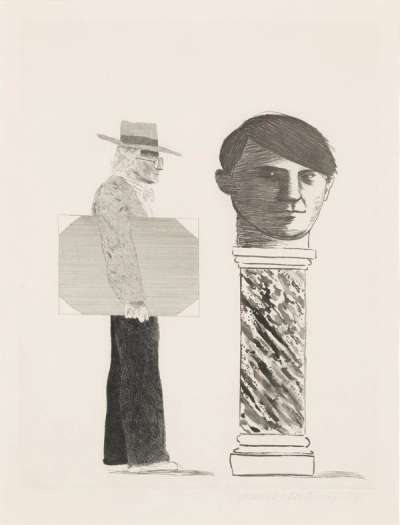

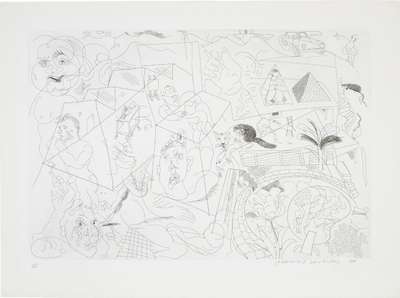

In prints such The Student dating to 1973 we see Hockney placing himself once again side by side with perhaps his greatest influence, Picasso, who died the same year. Similarly Artist and Model sees the young artist sitting across from the Spanish painter in a classic Hockney interior. Here Hockney appears to be in dialogue with the modernist master, incorporating him into a self portrait and even using him to show his talent for combining hard ground and soft ground etching, as evidenced by the different styles used for each figure. Here Picasso is rendered in looser, more watery lines while Hockney’s nude figure is more sketchy, incorporating cross hatching that suggests a sharper point. In contrast, the work entitled Doodle, overtly references the Cubist style rather than the father of Cubism himself.

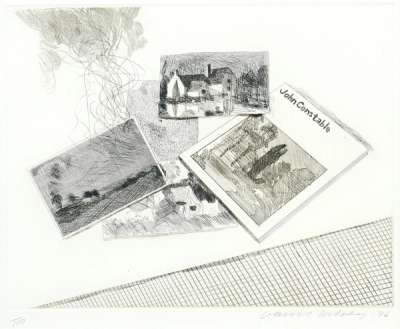

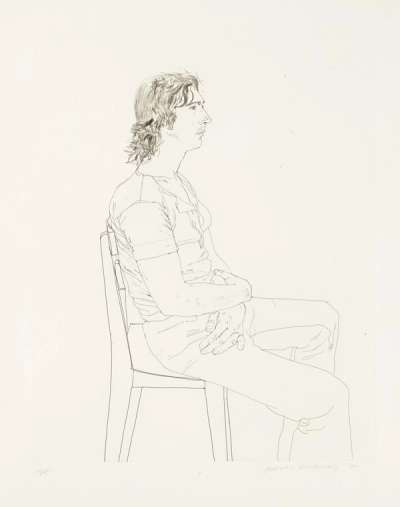

Turning to Hockney’s portrait of Auden we see the young painter placing the esteemed poet, who would die just three years later, centre stage, removing himself from the frame to allow our gaze to rest on the author of such masterpieces as ‘Funeral blues’ (perhaps better known as ‘Stop all the clocks’). With Hockney’s homages to John Constable and Michelangelo, however, we see him focus more on the work than the artists themselves; his 1975 intaglio dedicated to the Italian renaissance master even features a line from TS Eliot’s famous poem The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock: "In the room the women come and go / Talking of Michelangelo." Meanwhile Hockney’s tribute to Constable is an etching showing a set of postcards featuring reproductions of the British painter’s famous landscapes along with a pamphlet or exhibition guide bearing his name, as if to acknowledge the widespread popularity of his work.

Never one to hide his ability to emulate the work of others, to come up with new ideas based on ancient concepts, techniques and works of art and literature, Hockney wears his references on his sleeve. Just as series such as A Rake’s Progress, Illustrations For Fourteen Poems By C.P. Cavafy and Illustrations For Six Fairy Tales From The Brothers Grimm showcased his love of literature, so too do these homages to his heroes show us the incredible range of our most beloved living artist.