Salvador

Dali

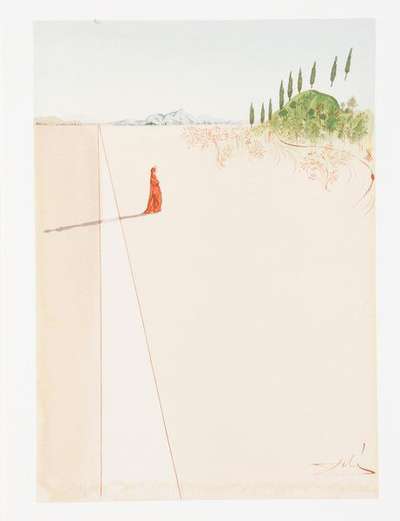

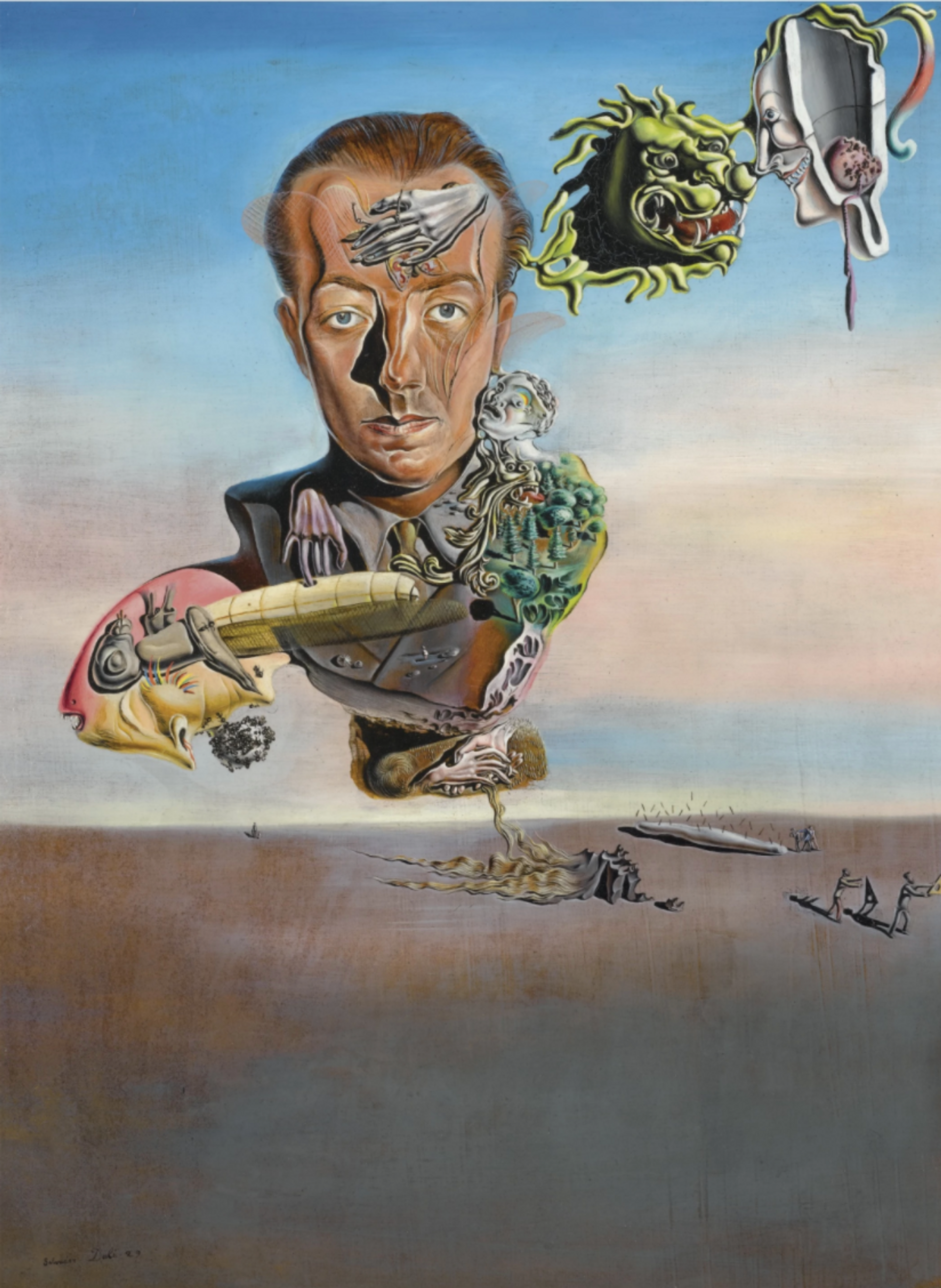

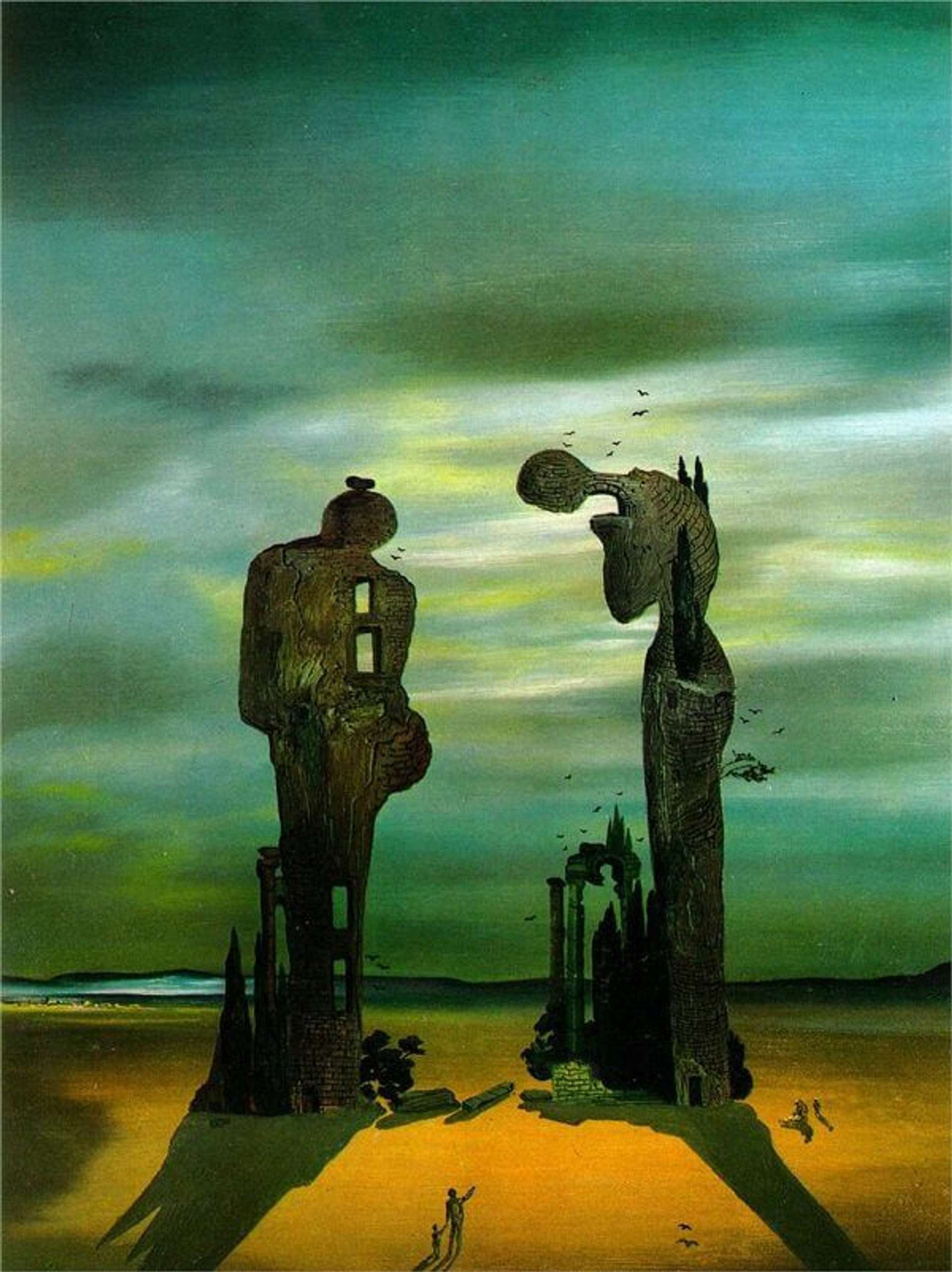

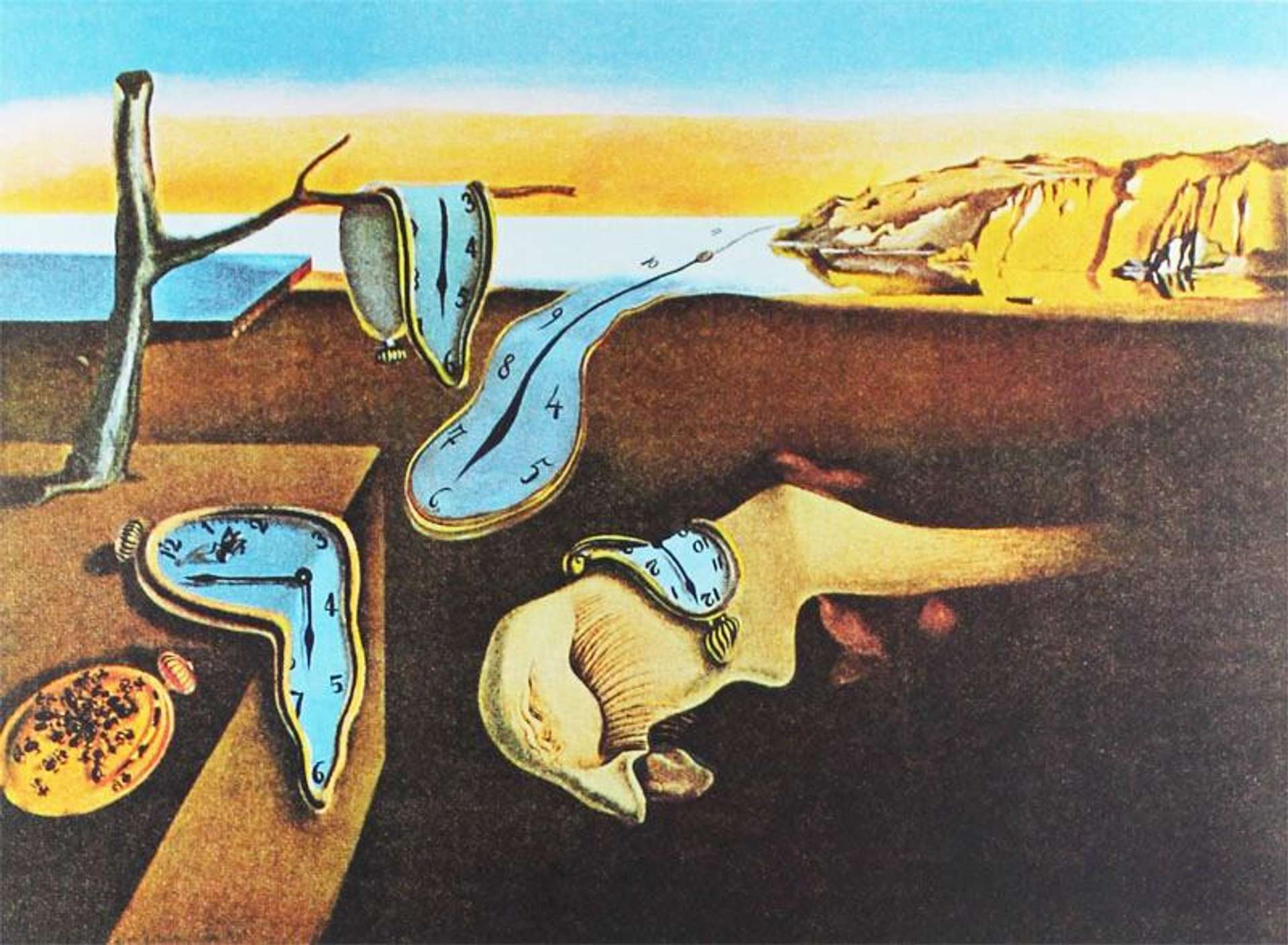

Synonymous with Surrealism, the eccentric Salvador Dali is a household name, thanks to his seminal contribution to Modern 20th century art. If you’re looking for original Dali prints and editions for sale or would like to sell, request a complimentary valuation and browse our network’s most in-demand works.

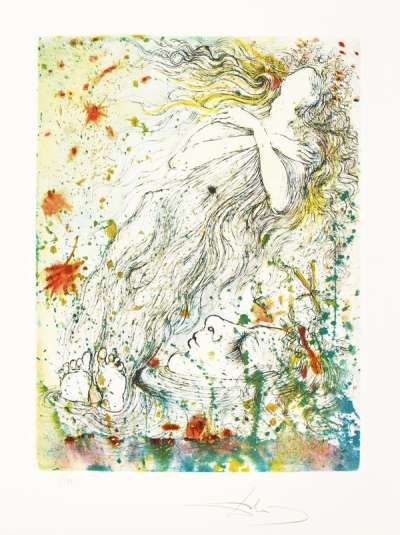

Salvador Dali prints for sale

£9,500-£14,000

$18,000-$27,000 Value Indicator

$16,000-$24,000 Value Indicator

¥90,000-¥130,000 Value Indicator

€11,000-€16,000 Value Indicator

$90,000-$140,000 Value Indicator

¥1,810,000-¥2,660,000 Value Indicator

$12,000-$18,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

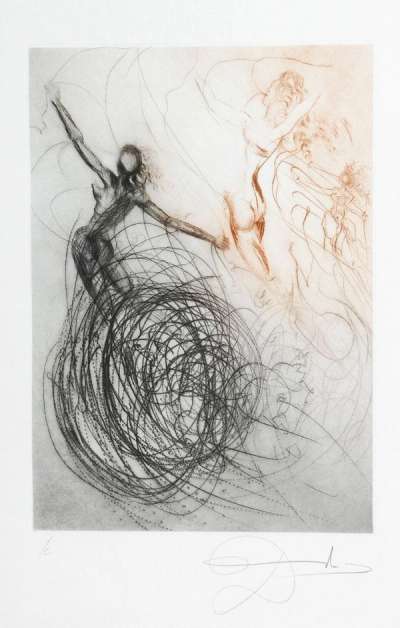

£13,500-£21,000

$26,000-$40,000 Value Indicator

$23,000-$35,000 Value Indicator

¥120,000-¥190,000 Value Indicator

€16,000-€25,000 Value Indicator

$130,000-$210,000 Value Indicator

¥2,570,000-¥4,000,000 Value Indicator

$17,000-$26,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

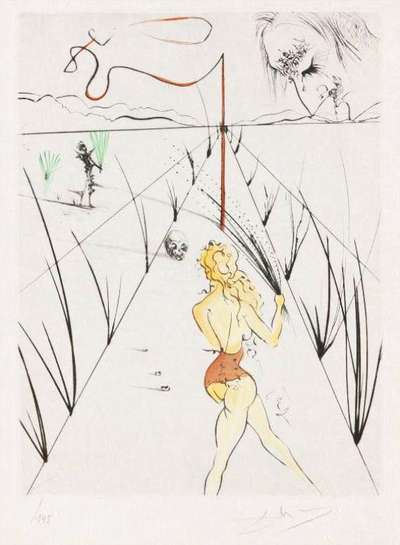

£5,500-£8,500

$10,500-$16,000 Value Indicator

$9,500-$14,500 Value Indicator

¥50,000-¥80,000 Value Indicator

€6,500-€10,000 Value Indicator

$50,000-$80,000 Value Indicator

¥1,040,000-¥1,610,000 Value Indicator

$7,000-$11,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

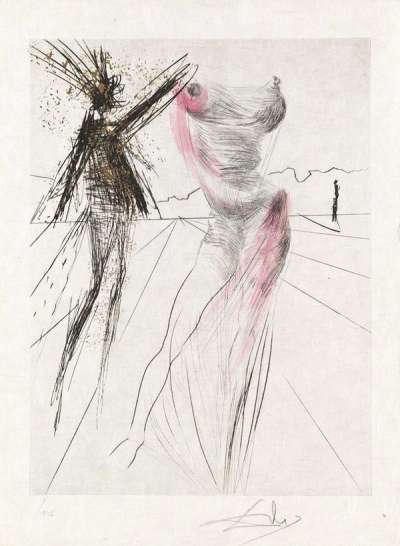

£2,900-£4,300

$5,500-$8,500 Value Indicator

$4,950-$7,500 Value Indicator

¥26,000-¥40,000 Value Indicator

€3,400-€5,000 Value Indicator

$28,000-$40,000 Value Indicator

¥550,000-¥820,000 Value Indicator

$3,650-$5,500 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£8,500-£13,000

$16,000-$25,000 Value Indicator

$14,500-$22,000 Value Indicator

¥80,000-¥120,000 Value Indicator

€10,000-€15,000 Value Indicator

$80,000-$130,000 Value Indicator

¥1,590,000-¥2,440,000 Value Indicator

$10,500-$16,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£750-£1,100

$1,450-$2,150 Value Indicator

$1,300-$1,850 Value Indicator

¥7,000-¥10,000 Value Indicator

€900-€1,300 Value Indicator

$7,500-$11,000 Value Indicator

¥140,000-¥210,000 Value Indicator

$950-$1,400 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£1,150-£1,700

$2,250-$3,300 Value Indicator

$1,950-$2,900 Value Indicator

¥10,500-¥15,000 Value Indicator

€1,350-€2,000 Value Indicator

$11,500-$17,000 Value Indicator

¥220,000-¥320,000 Value Indicator

$1,450-$2,150 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£5,500-£8,500

$10,500-$16,000 Value Indicator

$9,500-$14,500 Value Indicator

¥50,000-¥80,000 Value Indicator

€6,500-€10,000 Value Indicator

$50,000-$80,000 Value Indicator

¥1,050,000-¥1,620,000 Value Indicator

$7,000-$10,500 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£6,500-£9,500

$12,500-$18,000 Value Indicator

$11,000-$16,000 Value Indicator

¥60,000-¥90,000 Value Indicator

€7,500-€11,000 Value Indicator

$60,000-$90,000 Value Indicator

¥1,240,000-¥1,810,000 Value Indicator

$8,000-$12,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£2,650-£3,950

$5,000-$7,500 Value Indicator

$4,500-$6,500 Value Indicator

¥24,000-¥35,000 Value Indicator

€3,100-€4,600 Value Indicator

$26,000-$40,000 Value Indicator

¥500,000-¥750,000 Value Indicator

$3,300-$4,950 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£2,950-£4,450

$5,500-$8,500 Value Indicator

$5,000-$7,500 Value Indicator

¥27,000-¥40,000 Value Indicator

€3,450-€5,000 Value Indicator

$29,000-$45,000 Value Indicator

¥560,000-¥850,000 Value Indicator

$3,700-$5,500 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£1,950-£2,900

$3,750-$5,500 Value Indicator

$3,300-$4,950 Value Indicator

¥18,000-¥26,000 Value Indicator

€2,300-€3,400 Value Indicator

$19,000-$28,000 Value Indicator

¥370,000-¥550,000 Value Indicator

$2,450-$3,650 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£6,000-£8,500

$11,500-$16,000 Value Indicator

$10,000-$14,500 Value Indicator

¥50,000-¥80,000 Value Indicator

€7,000-€10,000 Value Indicator

$60,000-$80,000 Value Indicator

¥1,140,000-¥1,620,000 Value Indicator

$7,500-$10,500 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£6,500-£10,000

$12,500-$19,000 Value Indicator

$11,000-$17,000 Value Indicator

¥60,000-¥90,000 Value Indicator

€7,500-€11,500 Value Indicator

$60,000-$100,000 Value Indicator

¥1,240,000-¥1,910,000 Value Indicator

$8,000-$12,500 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£6,500-£9,500

$12,500-$18,000 Value Indicator

$11,000-$16,000 Value Indicator

¥60,000-¥90,000 Value Indicator

€7,500-€11,000 Value Indicator

$60,000-$90,000 Value Indicator

¥1,220,000-¥1,780,000 Value Indicator

$8,000-$12,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£9,500-£14,500

$18,000-$28,000 Value Indicator

$16,000-$25,000 Value Indicator

¥90,000-¥130,000 Value Indicator

€11,000-€17,000 Value Indicator

$90,000-$140,000 Value Indicator

¥1,810,000-¥2,760,000 Value Indicator

$12,000-$18,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£750-£1,150

$1,450-$2,250 Value Indicator

$1,300-$1,950 Value Indicator

¥7,000-¥10,500 Value Indicator

€900-€1,350 Value Indicator

$7,500-$11,500 Value Indicator

¥140,000-¥220,000 Value Indicator

$950-$1,450 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£850-£1,300

$1,650-$2,500 Value Indicator

$1,450-$2,200 Value Indicator

¥7,500-¥12,000 Value Indicator

€1,000-€1,500 Value Indicator

$8,500-$13,000 Value Indicator

¥160,000-¥240,000 Value Indicator

$1,050-$1,650 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£3,400-£5,000

$6,500-$9,500 Value Indicator

$6,000-$8,500 Value Indicator

¥30,000-¥45,000 Value Indicator

€3,950-€6,000 Value Indicator

$35,000-$50,000 Value Indicator

¥650,000-¥950,000 Value Indicator

$4,250-$6,500 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£4,850-£7,500

$9,500-$14,500 Value Indicator

$8,500-$13,000 Value Indicator

¥45,000-¥70,000 Value Indicator

€5,500-€9,000 Value Indicator

$50,000-$70,000 Value Indicator

¥920,000-¥1,430,000 Value Indicator

$6,000-$9,500 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£2,300-£3,500

$4,450-$7,000 Value Indicator

$3,950-$6,000 Value Indicator

¥21,000-¥30,000 Value Indicator

€2,700-€4,100 Value Indicator

$23,000-$35,000 Value Indicator

¥430,000-¥660,000 Value Indicator

$2,950-$4,450 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£4,550-£7,000

$9,000-$13,500 Value Indicator

$8,000-$12,000 Value Indicator

¥40,000-¥60,000 Value Indicator

€5,500-€8,000 Value Indicator

$45,000-$70,000 Value Indicator

¥860,000-¥1,320,000 Value Indicator

$6,000-$9,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£2,250-£3,350

$4,350-$6,500 Value Indicator

$3,850-$5,500 Value Indicator

¥20,000-¥30,000 Value Indicator

€2,650-€3,900 Value Indicator

$22,000-$35,000 Value Indicator

¥430,000-¥640,000 Value Indicator

$2,800-$4,200 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£2,850-£4,300

$5,500-$8,500 Value Indicator

$4,850-$7,500 Value Indicator

¥26,000-¥40,000 Value Indicator

€3,350-€5,000 Value Indicator

$28,000-$40,000 Value Indicator

¥530,000-¥810,000 Value Indicator

$3,600-$5,500 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£1,900-£2,850

$3,700-$5,500 Value Indicator

$3,250-$4,850 Value Indicator

¥17,000-¥26,000 Value Indicator

€2,200-€3,350 Value Indicator

$19,000-$28,000 Value Indicator

¥360,000-¥540,000 Value Indicator

$2,400-$3,600 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£650-£950

$1,250-$1,850 Value Indicator

$1,100-$1,600 Value Indicator

¥6,000-¥8,500 Value Indicator

€750-€1,100 Value Indicator

$6,500-$9,500 Value Indicator

¥120,000-¥180,000 Value Indicator

$800-$1,200 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£6,500-£10,000

$12,500-$19,000 Value Indicator

$11,000-$17,000 Value Indicator

¥60,000-¥90,000 Value Indicator

€7,500-€11,500 Value Indicator

$60,000-$100,000 Value Indicator

¥1,240,000-¥1,910,000 Value Indicator

$8,000-$12,500 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£15,000-£23,000

$29,000-$45,000 Value Indicator

$26,000-$40,000 Value Indicator

¥140,000-¥210,000 Value Indicator

€18,000-€27,000 Value Indicator

$150,000-$230,000 Value Indicator

¥2,850,000-¥4,380,000 Value Indicator

$19,000-$29,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£8,000-£12,000

$16,000-$23,000 Value Indicator

$13,500-$20,000 Value Indicator

¥70,000-¥110,000 Value Indicator

€9,500-€14,000 Value Indicator

$80,000-$120,000 Value Indicator

¥1,500,000-¥2,250,000 Value Indicator

$10,000-$15,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£14,000-£21,000

$27,000-$40,000 Value Indicator

$24,000-$35,000 Value Indicator

¥130,000-¥190,000 Value Indicator

€16,000-€25,000 Value Indicator

$140,000-$210,000 Value Indicator

¥2,660,000-¥4,000,000 Value Indicator

$18,000-$26,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£11,000-£17,000

$21,000-$35,000 Value Indicator

$19,000-$29,000 Value Indicator

¥100,000-¥150,000 Value Indicator

€13,000-€20,000 Value Indicator

$110,000-$170,000 Value Indicator

¥2,060,000-¥3,190,000 Value Indicator

$14,000-$21,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£11,500-£18,000

$22,000-$35,000 Value Indicator

$20,000-$30,000 Value Indicator

¥100,000-¥160,000 Value Indicator

€13,500-€21,000 Value Indicator

$110,000-$180,000 Value Indicator

¥2,190,000-¥3,430,000 Value Indicator

$14,500-$23,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£4,650-£7,000

$9,000-$13,500 Value Indicator

$8,000-$12,000 Value Indicator

¥40,000-¥60,000 Value Indicator

€5,500-€8,000 Value Indicator

$45,000-$70,000 Value Indicator

¥880,000-¥1,320,000 Value Indicator

$6,000-$9,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£1,750-£2,600

$3,400-$5,000 Value Indicator

$3,000-$4,450 Value Indicator

¥16,000-¥24,000 Value Indicator

€2,050-€3,050 Value Indicator

$17,000-$26,000 Value Indicator

¥330,000-¥490,000 Value Indicator

$2,200-$3,250 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£13,000-£20,000

$25,000-$40,000 Value Indicator

$22,000-$35,000 Value Indicator

¥120,000-¥180,000 Value Indicator

€15,000-€23,000 Value Indicator

$130,000-$200,000 Value Indicator

¥2,440,000-¥3,750,000 Value Indicator

$16,000-$25,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£2,600-£3,900

$5,000-$7,500 Value Indicator

$4,500-$6,500 Value Indicator

¥24,000-¥35,000 Value Indicator

€3,050-€4,550 Value Indicator

$26,000-$40,000 Value Indicator

¥490,000-¥740,000 Value Indicator

$3,300-$4,950 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£6,500-£9,500

$12,500-$18,000 Value Indicator

$11,000-$16,000 Value Indicator

¥60,000-¥90,000 Value Indicator

€7,500-€11,000 Value Indicator

$60,000-$90,000 Value Indicator

¥1,240,000-¥1,810,000 Value Indicator

$8,000-$12,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£19,000-£28,000

$35,000-$50,000 Value Indicator

$30,000-$50,000 Value Indicator

¥170,000-¥260,000 Value Indicator

€22,000-€35,000 Value Indicator

$190,000-$280,000 Value Indicator

¥3,620,000-¥5,340,000 Value Indicator

$24,000-$35,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£4,350-£6,500

$8,500-$12,500 Value Indicator

$7,500-$11,000 Value Indicator

¥40,000-¥60,000 Value Indicator

€5,000-€7,500 Value Indicator

$45,000-$60,000 Value Indicator

¥820,000-¥1,220,000 Value Indicator

$5,500-$8,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£1,300-£1,950

$2,500-$3,800 Value Indicator

$2,250-$3,350 Value Indicator

¥12,000-¥18,000 Value Indicator

€1,500-€2,300 Value Indicator

$13,000-$19,000 Value Indicator

¥250,000-¥370,000 Value Indicator

$1,650-$2,500 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£2,600-£3,950

$5,000-$7,500 Value Indicator

$4,400-$6,500 Value Indicator

¥24,000-¥35,000 Value Indicator

€3,050-€4,600 Value Indicator

$26,000-$40,000 Value Indicator

¥490,000-¥740,000 Value Indicator

$3,300-$5,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£11,000-£16,000

$21,000-$30,000 Value Indicator

$19,000-$27,000 Value Indicator

¥100,000-¥150,000 Value Indicator

€13,000-€19,000 Value Indicator

$110,000-$160,000 Value Indicator

¥2,090,000-¥3,050,000 Value Indicator

$14,000-$20,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£7,000-£10,500

$13,500-$20,000 Value Indicator

$12,000-$18,000 Value Indicator

¥60,000-¥100,000 Value Indicator

€8,000-€12,500 Value Indicator

$70,000-$100,000 Value Indicator

¥1,310,000-¥1,970,000 Value Indicator

$9,000-$13,500 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£1,050-£1,600

$2,050-$3,100 Value Indicator

$1,800-$2,700 Value Indicator

¥9,500-¥14,500 Value Indicator

€1,250-€1,850 Value Indicator

$10,500-$16,000 Value Indicator

¥200,000-¥300,000 Value Indicator

$1,350-$2,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£3,500-£5,500

$7,000-$10,500 Value Indicator

$6,000-$9,500 Value Indicator

¥30,000-¥50,000 Value Indicator

€4,100-€6,500 Value Indicator

$35,000-$50,000 Value Indicator

¥660,000-¥1,030,000 Value Indicator

$4,400-$7,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£4,800-£7,000

$9,500-$13,500 Value Indicator

$8,000-$12,000 Value Indicator

¥45,000-¥60,000 Value Indicator

€5,500-€8,000 Value Indicator

$45,000-$70,000 Value Indicator

¥910,000-¥1,330,000 Value Indicator

$6,000-$9,000 Value Indicator

TradingFloor

£11,500-£18,000

$22,000-$35,000 Value Indicator

$20,000-$30,000 Value Indicator

¥110,000-¥170,000 Value Indicator

€13,500-€21,000 Value Indicator

$110,000-$180,000 Value Indicator

¥2,170,000-¥3,400,000 Value Indicator

$14,500-$23,000 Value Indicator

£6,500-£10,000

$12,500-$19,000 Value Indicator

$11,000-$17,000 Value Indicator

¥60,000-¥90,000 Value Indicator

€7,500-€11,500 Value Indicator

$60,000-$100,000 Value Indicator

¥1,240,000-¥1,900,000 Value Indicator

$8,000-$12,500 Value Indicator

£7,000-£10,000

$13,500-$19,000 Value Indicator

$12,000-$17,000 Value Indicator

¥60,000-¥90,000 Value Indicator

€8,000-€11,500 Value Indicator

$70,000-$100,000 Value Indicator

¥1,310,000-¥1,870,000 Value Indicator

$9,000-$12,500 Value Indicator

£10,000-£15,000

$19,000-$29,000 Value Indicator

$17,000-$26,000 Value Indicator

¥90,000-¥140,000 Value Indicator

€11,500-€18,000 Value Indicator

$100,000-$150,000 Value Indicator

¥1,870,000-¥2,810,000 Value Indicator

$12,500-$19,000 Value Indicator

£5,500-£8,000

$10,500-$15,000 Value Indicator

$9,500-$13,500 Value Indicator

¥50,000-¥70,000 Value Indicator

€6,500-€9,500 Value Indicator

$50,000-$80,000 Value Indicator

¥1,030,000-¥1,500,000 Value Indicator

$7,000-$10,000 Value Indicator

£6,500-£9,500

$12,500-$18,000 Value Indicator

$11,000-$16,000 Value Indicator

¥60,000-¥90,000 Value Indicator

€7,500-€11,000 Value Indicator

$60,000-$90,000 Value Indicator

¥1,220,000-¥1,780,000 Value Indicator

$8,000-$12,000 Value Indicator

£1,000-£1,500

$1,950-$2,900 Value Indicator

$1,700-$2,550 Value Indicator

¥9,000-¥13,500 Value Indicator

€1,150-€1,750 Value Indicator

$10,000-$15,000 Value Indicator

¥190,000-¥280,000 Value Indicator

$1,250-$1,900 Value Indicator

£6,500-£10,000

$12,500-$19,000 Value Indicator

$11,000-$17,000 Value Indicator

¥60,000-¥90,000 Value Indicator

€7,500-€11,500 Value Indicator

$60,000-$100,000 Value Indicator

¥1,220,000-¥1,870,000 Value Indicator

$8,000-$12,500 Value Indicator

Sell Your Art

with Us

with Us

Join Our Network of Collectors. Buy, Sell and Track Demand

Biography

Ultimate Surrealist Salvador Dali’s work spans painting, sculpture, and performance, blurring the boundaries between art and life, reality and dream. Working across painting, sculpture, film, photography and even fiction and poetry, Dali was known for both his artwork and his raucous public persona. A controversial figure both during and after his lifetime, Dali is a name synonymous with the bizarre and the dramatic in art history.